You’re sitting in a coffee shop. You look at the menu and see a $400 bottle of rare vintage wine. You want it. You really, really want it. But you’ve only got twenty bucks in your pocket and a maxed-out credit card. In the world of economics, does your desire for that wine matter?

Not even a little bit.

When people ask which of the following specifically refers to demand, they are usually looking for a specific term that separates "wishing for something" from "actually being able to buy it." That term is effective demand. It’s a concept that sounds dry but actually dictates why some businesses explode in growth while others, despite having a product everyone "loves," go completely bust.

Why Desire Isn't Demand

Most folks use the word "demand" loosely. They think if a million people follow a brand on Instagram, there’s high demand. That’s a trap. Economists like John Maynard Keynes—the guy who basically redefined how we look at modern macroeconomics—argued that for demand to mean anything in a market, it has to be backed by the ability to pay.

Think about the Ferrari Roma. I want one. You probably want one. But if Ferrari looks at a room full of a thousand people who want the car but can only afford a 2012 Honda Civic, they don't see demand. They see "notional demand" or "latent demand." It’s essentially a wishlist.

Effective demand is different. It is the point where the desire to possess something meets the actual purchasing power to acquire it. It’s the only metric that moves the needle on a balance sheet.

The Keynesian Perspective and Why It Hits Different

Keynes wasn't just obsessed with math; he was obsessed with why economies collapse. In his landmark 1936 work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, he flipped the script on "Say’s Law." Old-school economists used to think that supply creates its own demand. Basically, they thought if you build it, they will come because the act of producing goods creates wages for workers, who then spend that money.

Keynes said: "Hold on."

He realized that if people get scared and start hoarding cash, that cycle breaks. Even if there are plenty of goods on the shelves, if nobody has the confidence or the liquidity to buy them, effective demand craters. This is exactly what happened during the Great Depression. There were plenty of factories and plenty of workers, but the "effective" part of the demand equation was missing. People didn't have the money. Or if they did, they weren't spending it.

The Real-World Impact of Misjudging Demand

Look at the tech hardware space. Remember the "Juicero"? It was a $700 juicer that squeezed proprietary packets of fruit. Everyone talked about it. It was a viral sensation. People desired the convenience of fresh juice without the mess. But when it came down to actually swiping a card for seven hundred bucks? The effective demand was non-existent. The market for "people who want juice" was huge. The market for "people who will pay $700 for a machine that does what their hands can do for free" was a sliver.

🔗 Read more: Why 38 East 32nd Street is the No-Nonsense Heart of NoMad Real Estate

It’s a brutal lesson in market research.

Factors That Actually Move the Needle

What actually creates this specific type of demand? It isn’t just marketing. It’s a cocktail of three specific things:

- Utility: You actually have to need or want the thing. It has to solve a problem or scratch an itch.

- Purchasing Power: You need the cash, the credit, or the tradeable assets.

- Willingness to Spend: This is the psychological part. You might have $100,000 in the bank, but if you think a recession is coming tomorrow, your demand for a new luxury watch effectively hits zero.

When economists try to predict where the housing market is going, they don't look at how many people want a house. Everyone wants a house. They look at mortgage rates and wage growth. When rates go up, effective demand drops because fewer people can afford the monthly payment. The desire is still there, but the "effective" part has been stripped away.

Price Elasticity: The Invisible Hand’s Best Friend

We should probably talk about price. It’s the most obvious lever.

If a bakery sells a croissant for $3, they might sell 500 a day. If they raise the price to $15, they might only sell five. The "desire" for a croissant hasn't changed. People still like butter and carbs. What changed was the intersection of that desire and the perceived value of the money in their pocket. This is what we call "price elasticity of demand."

Some things are inelastic. If the price of insulin goes up, effective demand stays relatively stable because people literally need it to live. They will sacrifice food, clothing, and Netflix to pay for it. If the price of a fancy latte goes up, people just drink the swill in the office breakroom.

Common Misconceptions About What "Refers to Demand"

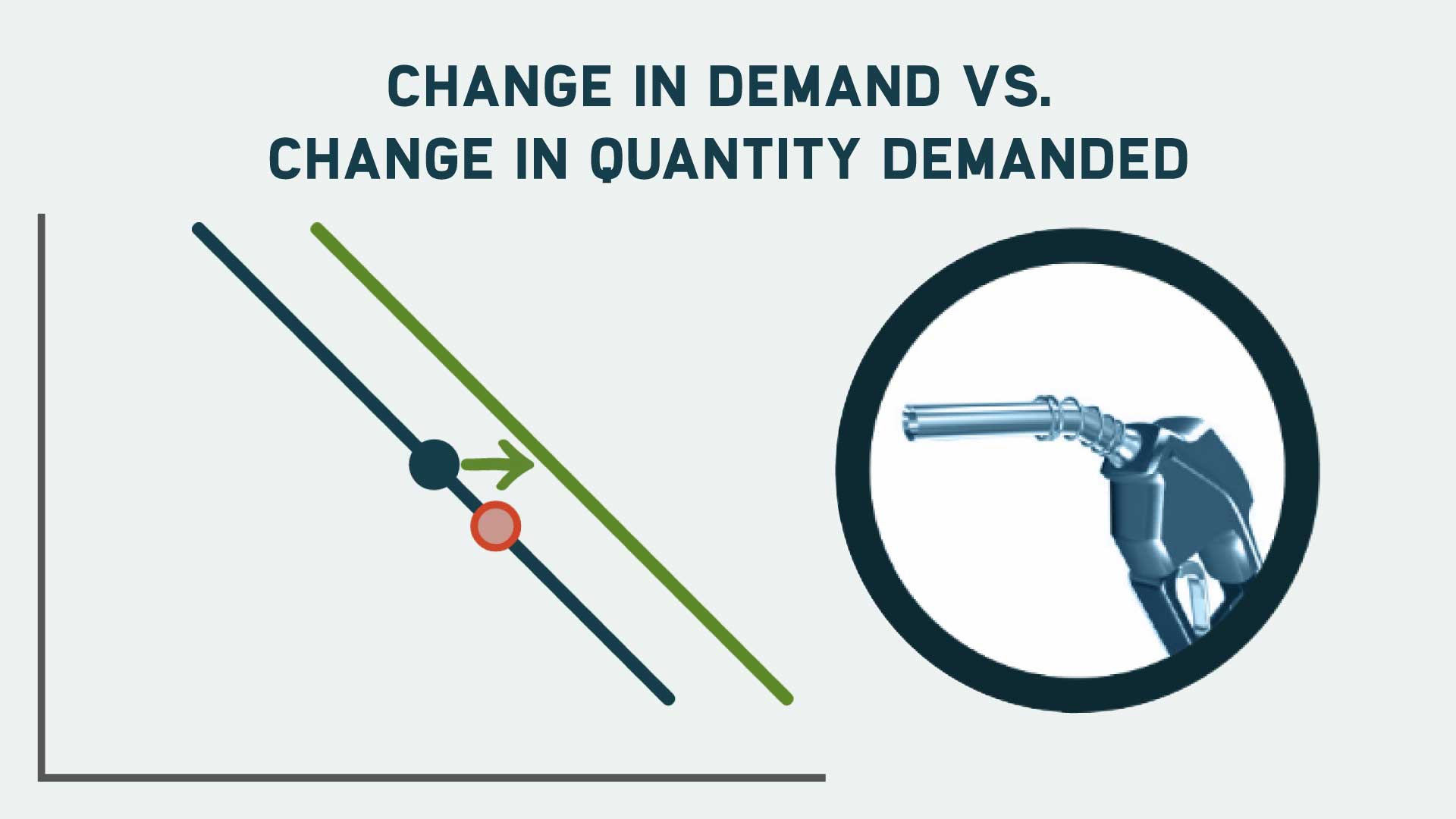

You’ll often see people confuse "Demand" with "Quantity Demanded." It sounds like pedantic wordplay, but it’s a big deal if you're trying to pass an exam or run a business.

- Demand refers to the entire relationship between price and how much people want to buy. It’s the whole curve on the graph.

- Quantity Demanded is just a specific point. At $5, we want 10 units. That "10" is the quantity demanded.

Then there's the "Derived Demand" trap. This happens in the B2B world. The demand for steel isn't because people just love owning lumps of metal. It's because people want cars and skyscrapers. If people stop buying cars, the effective demand for steel vanishes. It’s a chain reaction.

📖 Related: The Panic of 1837: What Really Happened When the American Economy Collapsed

The Role of Credit in Boosting Demand

In modern economies, we’ve found a way to "cheat" the system of effective demand: Credit.

By allowing people to spend money they haven't earned yet, we artificially inflate effective demand. This is great for the economy in the short term—it keeps factories running and people employed—but it creates a bubble. If everyone is buying stuff on credit, the "demand" is real in the sense that the goods are moving, but it’s fragile. If the credit taps turn off, the demand evaporates instantly.

We saw this in 2008. The demand for houses was "effective" only as long as subprime loans were available. Once the banks realized those loans wouldn't be paid back, the "effective" part of the demand disappeared, and the market imploded.

How Businesses Use This to Survive

If you’re running a company, you don't care about "interest." You care about "conversions."

Marketing teams often focus on building brand awareness (which builds notional demand). Sales teams focus on closing the deal (which captures effective demand). A smart business strategy involves finding a segment of the population where your price point matches their "willingness and ability."

Luxury brands like Hermès are masters of this. They don't want everyone to be able to buy a Birkin bag. They intentionally keep the price high to ensure that only a specific level of effective demand exists. This creates scarcity, which—ironically—increases the desire (notional demand) among everyone else. It’s a psychological loop.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Market Demand

Honestly, whether you're an investor, a student, or a business owner, you have to look past the hype. Forget the "likes" and the "shares." They are vanity metrics that represent interest, not demand.

- Audit the "Ability to Pay": If you are launching a product, don't just ask people if they like it. Ask them what they would give up to buy it. If they wouldn't skip two Starbucks coffees to pay for your app, you don't have effective demand.

- Watch the Macro Trends: Keep an eye on interest rates and inflation. When inflation eats into disposable income, the first thing to die is effective demand for "wants" rather than "needs."

- Differentiate Your Demand: Is people's desire for your work "derived"? If you're a freelance graphic designer for real estate agents, your demand is derived from the housing market. If houses aren't selling, your phone stops ringing.

- Focus on the Friction: Sometimes effective demand is blocked by friction, not money. If your checkout process is a nightmare, you are killing demand at the finish line.

Understanding that demand isn't just a feeling—it's a financial capability—changes how you see the world. It’s the difference between a hobby and a market. It’s the difference between a dream and a deal. Next time you see a "trending" product, ask yourself if people are actually opening their wallets, or if they're just window shopping in the digital age.

To truly master this, start by analyzing your own spending. Look at the last five things you bought. You had the desire, yes. But you also had the specific "effective" trigger—the right price, at the right time, with enough money in the bank to justify the trade. That is the engine of the global economy.

Analyze your target audience's liquid assets before launching a high-ticket item. Check the consumer confidence index (CCI) to gauge the "willingness" side of the demand equation. Pivot your marketing from "awareness" to "incentivized action" when you notice a dip in market participation. These steps turn theoretical economic knowledge into a practical business advantage.