You’ve probably stood in a massive public building and felt that weird, heavy sense of "important art" looming over you. Most of the time, those murals feel like dusty homework. But if you ever find yourself in the Boston Public Library or the Pennsylvania State Capitol, the vibe changes. You’re looking at the work of Edwin Austin Abbey, a man who basically treated a paintbrush like a film camera decades before Hollywood figured out how to make an epic.

Honestly, it’s kind of wild that we don't talk about him more. In the late 1800s, Edwin Austin Abbey was the guy. He was the superstar illustrator who moved to England, became best friends with John Singer Sargent, and ended up painting the official coronation of King Edward VII.

He wasn't just some guy who liked old clothes. He was obsessed with them.

The American Who "Out-Englished" the British

Born in Philadelphia in 1852, Abbey started out as a teenage prodigy for Harper’s Weekly. He had this almost supernatural ability to make pen-and-ink drawings feel like they were breathing. By the time he was 26, his bosses sent him to England to gather "background material" for some poems he was illustrating. He went for a trip and basically never left.

Abbey fell hard for the English countryside. He eventually settled in a massive house in Gloucestershire called Morgan Hall, where he built what was reportedly the largest private studio in Europe.

He became so integrated into the British elite that they offered him a knighthood. He turned it down. Why? Because he didn't want to give up his American citizenship. He was a Philly kid at heart, even if he did spend his weekends playing cricket with his buddy Sargent.

That Obsession with Accuracy

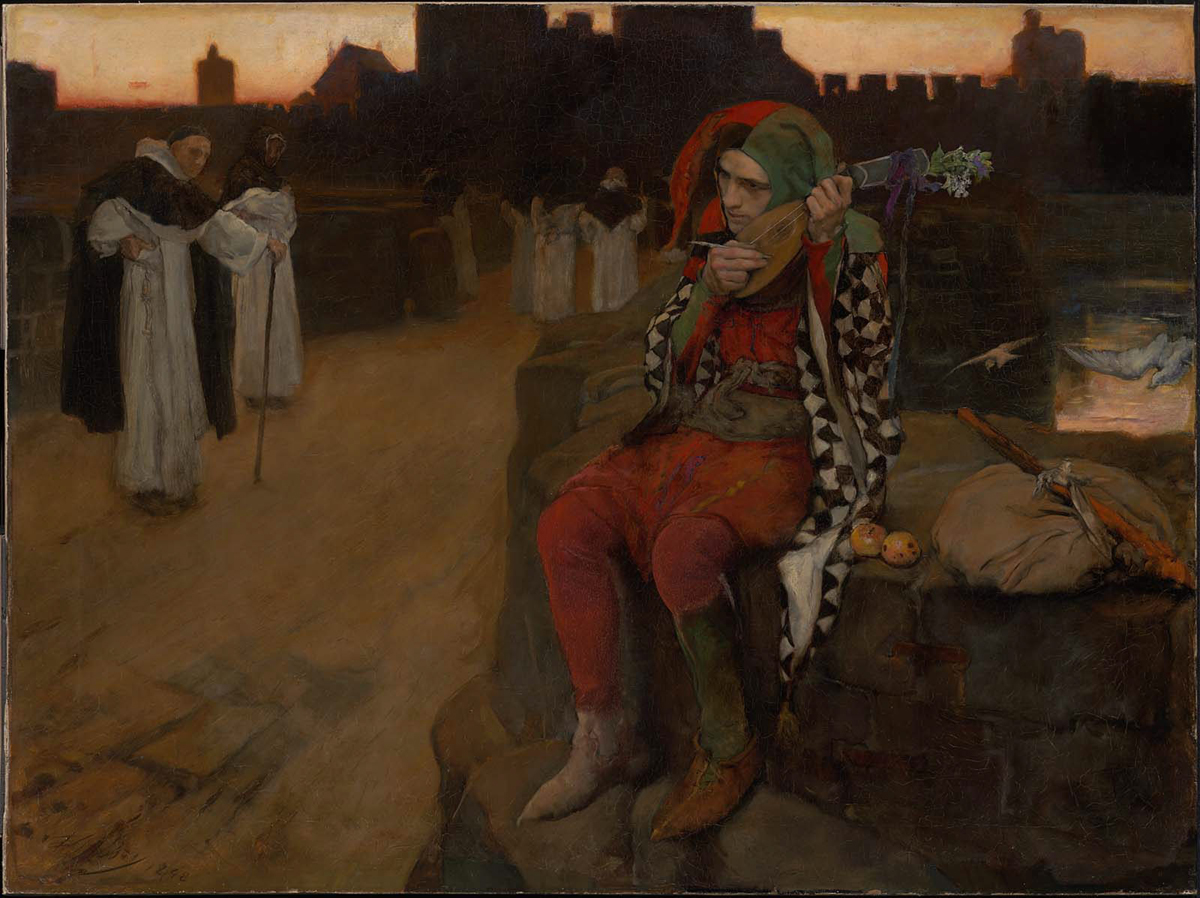

If you look at an Edwin Austin Abbey artist piece today, the first thing you notice is the detail. It’s not just "old-timey" fluff.

The man was a research nut. He collected authentic period costumes like a modern-day cosplayer. If he was painting a scene from Shakespeare, he wouldn't just guess what a doublet looked like. He’d find a real one, or have it painstakingly recreated. There’s a famous story about him painting a funeral procession in Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and the Lady Anne. He originally painted all the pikes with the blades facing up. Then he found out that wasn't historically accurate for a funeral, so he repainted every single one of them.

👉 See also: Debbie Does Dallas Streaming: What Really Happened With This Public Domain Legend

That’s the kind of dedication that makes his work feel "real" even when it's depicting 500-year-old legends.

The Murals: Why You Should Care

If you want to see what Abbey was really capable of, you have to go to Boston. His series The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Grail is just... massive. It’s fifteen panels of Arthurian legend that wrap around the Book Delivery Room.

- The Cinematic Flow: The panels aren't just static images. They follow Sir Galahad (always in a bright red robe) as he moves through his life. It’s basically a 19th-century storyboard.

- The "Raised Relief" Trick: Abbey and Sargent used to hang out and swap tips. One of them was using "raised relief"—basically building up the paint or using plaster so that things like Galahad’s golden tree or the Grail itself actually stick out from the wall. It’s 3D art from 1901.

- The Drama: In the panel where Galahad sits in the "Siege Perilous" (the seat where anyone but the chosen knight dies), you can practically feel the tension in the room.

He did the same thing for the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg. He spent the last years of his life working on a huge program of murals there. The most famous one, The Apotheosis of Pennsylvania, features William Penn, Ben Franklin, and a bunch of other historical heavyweights standing on a rock.

A Career That Ended in the Middle of a Brushstroke

Abbey’s life didn't have a slow fade-out. He was right in the middle of his biggest projects when he was diagnosed with cancer. He died in 1911 at 59 years old.

At the time of his death, he was still working on the murals for the Pennsylvania Capitol. He actually left a bunch of them unfinished. His assistant, William Simmonds, had to help wrap things up, and eventually, the commission was handed over to Violet Oakley.

It’s a bit of a tragedy, really. He was at the absolute peak of his powers, blending the technical skill of the Old Masters with a very modern, almost "theatrical" sensibility.

What People Get Wrong About Abbey

People often lump him in with the "Pre-Raphaelites" because he liked medieval stuff. While he definitely shared their love for the past, Abbey was much more grounded in reality. He wasn't trying to be "dreamy." He was trying to be accurate.

✨ Don't miss: Saving Private Ryan Parent Guide: Is It Too Intense for Your Teen?

He also gets dismissed sometimes as "just an illustrator." That’s a mistake. In the 19th century, illustration was where the innovation was happening. He brought a level of psychological depth to Shakespeare’s characters that most "fine artists" couldn't touch. When you look at his Hamlet, you aren't just seeing a scene from a play; you’re seeing the actual internal rot of the Danish court.

How to Experience Abbey Today

If you're into art history or just like cool stories, here is how you actually "do" Edwin Austin Abbey:

- Visit the Yale University Art Gallery: They have the largest collection of his work, including a ton of his sketches and the studies for his murals. Seeing his "rough" work is actually better for learning his process than seeing the finished pieces.

- The Boston Public Library: Don't just look at the Sargent murals upstairs (which everyone does). Spend some time in the Abbey Room. Look for the way the light hits the raised gold on the Grail.

- The National Gallery (London): If you're in the UK, keep an eye out for their recent exhibitions. As of early 2026, they've been doing a major push to reintroduce his work to the public, specifically his "By the Dawn's Early Light" series.

- Look at his Shakespeare Comedies: Grab a used copy of the Comedies of William Shakespeare illustrated by Abbey. It’s a masterclass in how to use black and white to create mood.

The truth is, we live in a world of CGI and hyper-fast cuts. Taking a second to look at a 12-foot-wide painting that took a man years to research and execute is a different kind of "epic." Abbey was a bridge between the old world of history painting and the new world of visual storytelling. He basically invented the "look" of the historical epic before the first movie camera even started rolling.

Next Steps for Art Lovers:

To truly understand Abbey's technique, search for high-resolution scans of his pen-and-ink work for Harper's Monthly. Pay close attention to his "cross-hatching" and how he creates light without using a single drop of white paint. If you can, plan a trip to Harrisburg or Boston to see the murals in person—no photograph can capture the scale and texture of his raised-relief gold work.