The family PC in 2004 was a sacred, beige altar. If you grew up then, you remember the ritual: the mechanical clack of a jewel case opening, the whir of the CD-ROM drive spinning up like a jet engine, and that specific, pixelated glow of a splash screen. It wasn’t just about killing time. We were actually doing homework, but the kind that didn't feel like a chore because we were busy managing a zoo or solving a mystery in a haunted museum. Educational computer games from the 2000s were in a league of their own. They didn't have the microtransactions of today's mobile apps or the hyper-polished graphics of modern consoles. They had soul. And honestly? They were surprisingly hard.

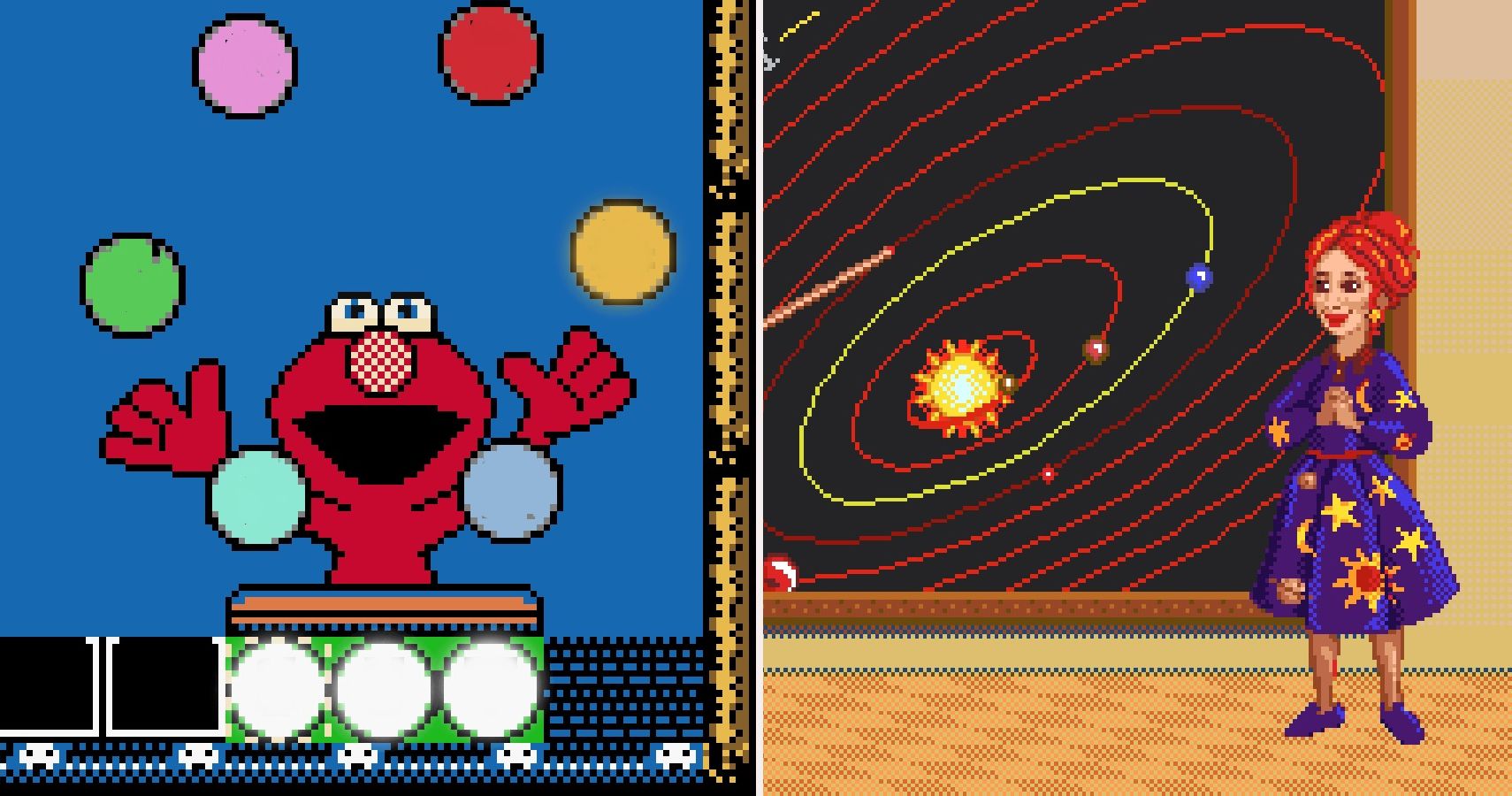

Most people think of this era as just a bridge between the 8nd-bit "Oregon Trail" days and the "Minecraft" explosion. That’s a mistake. The 2000s were the sweet spot of "edutainment." Developers like Humongous Entertainment, The Learning Company, and Scholastic were operating at their peak, blending legitimate pedagogical theories with genuine gameplay loops. You weren't just clicking on a math problem; you were navigating a world where math was the key to the door.

The Humongous Entertainment dominance

You can't talk about this decade without mentioning Ron Gilbert and Humongous Entertainment. While Gilbert is famous for Monkey Island, his impact on children’s cognitive development through point-and-click adventures is massive. Games like Putt-Putt Joins the Circus or Freddi Fish 3: The Case of the Stolen Conch Shell were masterclasses in logical sequencing.

They taught us if-then logic before we knew what a coding variable was. To get the magnetic wand, you needed the blue stone. To get the blue stone, you had to win the shell-shell game. To win the game, you needed a specific coin. It was recursive problem-solving. It’s the kind of stuff that builds "executive function," a buzzword psychologists use today, but back then, we just called it "not getting stuck."

Pajama Sam: No Need to Hide When It's Dark Outside remains a standout. It tackled childhood anxiety through the lens of a classic adventure game. Sam wasn't a superhero. He was a kid in a cape who lost his flashlight. The game used randomized paths, meaning the items you needed changed every time you played. This forced kids to actually explore and adapt rather than just memorizing a walkthrough. It was brilliant.

When "The Learning Company" ruled the classroom

If your school had a computer lab, you played Zoombinis. Specifically, Logical Journey of the Zoombinis. This game is legendary among millennials and Gen Z for a reason. It didn't hold your hand. It was brutal.

💡 You might also like: Why The Forest Game Mutants Still Give Us Nightmares After All These Years

The "Allergic Cliffs" level is a core memory for millions. You had to deduce which facial features the cliffs "disliked" based on their reactions. It was pure pattern recognition and set theory. No instructions. No tutorial. Just trial, error, and the devastating sound of a Zoombini being blasted back to the start. Dr. Chris Hancock, who designed the game at TERC, intentionally built it to mirror real mathematical thinking. It wasn't about arithmetic; it was about the logic behind the numbers.

Then there was ClueFinders. This series took the Scooby-Doo formula and injected it with high-stakes mystery. The ClueFinders 3rd Grade Adventure: Mystery of Mathra or the 4th Grade Egyptian mystery felt like real adventures. They used a "Progress Tracker" that actually adjusted the difficulty of the puzzles based on how well you were doing. This is "Adaptive Learning," a cornerstone of modern educational tech, but they were doing it on Windows 98.

The rise of simulation and the "hidden" curriculum

Some of the best educational computer games from the 2000s weren't even sold as educational. They were simulations.

RollerCoaster Tycoon (released in '99 but a staple of the early 2000s) taught a generation about microeconomics. You learned that if you charged too much for fries, people got thirsty. If you charged for the bathroom right after they ate the fries, you were a genius—or a villain. You were managing staff wages, research and development budgets, and guest happiness metrics.

Zoo Tycoon was similar. It taught biology and ecology. If you put a lion in a cage with a gazelle, you learned about the food chain very quickly. You had to balance the pH levels of the water for the marine animals and ensure the foliage matched the biome of the Siberian Tiger. It was systems thinking. It taught us that every action in a complex environment has a ripple effect.

A few titles that defined the era:

- JumpStart series: The gold standard for grade-specific curriculum, from JumpStart Advanced 1st Grade to their later 3D worlds.

- Reader Rabbit: The undisputed king of phonics and early literacy.

- Nancy Drew: Her interactive mysteries by Her Interactive taught deductive reasoning and historical research to an older demographic.

- Backyard Sports: While mostly sports, the drafting and stat-tracking provided a sneaky introduction to data analysis and probability.

Why the 2000s formula worked better than today

Modern educational games often feel like "chocolate-covered broccoli." The "game" part is a thin veneer over a boring quiz. If you answer five math questions, you get to shoot a digital basketball. That’s not game design; that’s a bribe.

In the 2000s, the learning was the game. You couldn't progress in I Spy Spooky Mansion without practicing visual discrimination and vocabulary. The mechanics were baked into the narrative. There was also a sense of "completionism." You bought a disc, you played it until you won, and you owned that experience. Today's "Software as a Service" (SaaS) model for kids' apps often involves endless loops designed to keep eyes on screens rather than reaching a "eureka" moment.

There was also a weirdness to these games. They were often a bit creepy or surreal. Think about the art style of Starfall or the bizarre characters in Cosmo’s Cosmic Adventure. That aesthetic "friction" made them memorable. They didn't feel like they were scrubbed clean by a corporate focus group. They felt like they were made by people who actually liked kids and wanted to weird them out a little bit while teaching them about fractions.

The technical hurdle: Why we can't play them anymore

It’s actually heartbreaking how much of this history is "bit-rotting" away. Most educational computer games from the 2000s were built for 32-bit operating systems or relied on QuickTime and Flash. If you try to pop a 2002 Scholastic disc into a Windows 11 machine today, it’ll probably just laugh at you.

Preservationists are working hard, though. Sites like the Internet Archive and projects like ScummVM have made many of these titles playable in a browser. But the context is gone. Playing Oregon Trail 5th Edition in a browser tab isn't the same as sitting in a plastic chair in the school basement, hoping the teacher doesn't see you're actually just hunting buffalo instead of reading the diary entries.

The industry moved toward mobile, and with it, the depth of these experiences changed. We traded the complex, narrative-driven puzzles of The Magic School Bus Explores the Solar System for short-burst "brain training" games. We lost something in that trade. We lost the immersion.

Making these games work for you today

If you’re a parent, a teacher, or just a nostalgic nerd, you don't have to let these games stay in the past. There are actual, practical ways to use this "edutainment" philosophy right now.

First, check the Internet Archive’s Software Library. They have a massive collection of "abandonware" that runs via an in-browser emulator. You can show a kid Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? without needing an old PC. It still holds up because geography hasn't changed that much, and the logic puzzles are timeless.

Second, look at GOG.com (Good Old Games). They’ve actually optimized several Humongous Entertainment titles to run on modern hardware. They are cheap, DRM-free, and perfect for a rainy afternoon.

Third, pay attention to the Indie Scene. Modern games like Strange Horticulture or Return of the Obra Dinn are essentially the spiritual successors to the 2000s educational mystery genre. They trust the player's intelligence. They don't give you a waypoint marker; they give you a notebook and tell you to figure it out.

🔗 Read more: How to Get the Somberstone Miner's Bell Bearing 1 Without Losing Your Mind

The legacy of educational computer games from the 2000s isn't just nostalgia. It’s a blueprint for how to make learning feel like an adventure. We learned how to manage resources, how to think logically, and how to persevere through "game over" screens. We should probably start demanding that same level of depth from the educational tools we use today.

Practical Next Steps:

- Inventory your old tech: If you still have a stash of CD-ROMs, don't toss them. Check if they are 16-bit or 32-bit. 32-bit games can sometimes be coaxed to work on modern PCs using "Compatibility Mode," though it's hit-or-miss.

- Support Preservation: If you find a rare title that isn't online, consider reaching out to the Strong National Museum of Play. They specialize in preserving the history of electronic games.

- Emulate safely: Use ScummVM. It’s a free tool that allows you to run many of these classic adventure games on everything from your phone to your desktop. It’s the most stable way to revisit Putt-Putt or Freddi Fish without the crashes.

- Look for "System-Based" games: When choosing modern games for kids, look for "Sim" titles that mirror the 2000s style. Games like Planet Zoo or Cities: Skylines carry the torch of the "Tycoon" era and offer a much deeper educational experience than standard "Math Apps."