He’s the guy with the raven. The guy who got buried alive—in his stories, anyway. Most of us met him in a dusty middle school classroom where "The Tell-Tale Heart" was forced upon us like a chore. But if you actually sit down with Edgar Allan Poe the complete works, you realize the "Master of Macabre" label is kinda reductive. It’s like calling Prince just a guitar player. Poe was a frantic, broke, brilliant editor who essentially invented the detective story because he was obsessed with logic, not just ghosts.

Honestly, reading his entire output is a chaotic experience. You expect constant gloom. Instead, you get weirdly technical essays on interior design, slapstick humor that honestly hasn't aged that well, and "Eureka," a prose poem where he basically predicts the Big Bang theory a century before anyone else.

The Mystery of the First Edition

Finding a "complete" collection isn't as straightforward as grabbing a paperback at the airport. Poe died in 1849 under circumstances that are still, frankly, a total mess. Because he was perpetually dodging debt collectors and lived a life of nomadic literary desperation, his writings were scattered across dozens of magazines and journals.

The first attempt to pull it all together was handled by Rufus Wilmot Griswold. Here’s the kicker: Griswold hated Poe. Like, really hated him. He wrote a scathing obituary and then edited the first posthumous collection of Edgar Allan Poe the complete works while simultaneously trying to assassinate Poe’s character. He forged letters to make Poe look like a drug-addled madman. For decades, the world read Poe through the lens of a guy who wanted to ruin him. It took years of scholarship—real, gritty archival work—to separate the man from the myth Griswold manufactured.

More Than Just Spooky Birds

When you dive into the full bibliography, you see the range. Most people know the big hitters: "The Raven," "The Pit and the Pendulum," "The Fall of the House of Usher." But have you read "The Murders in the Rue Morgue"?

That story changed everything.

🔗 Read more: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

Before Poe, there wasn't really a "detective" genre. There were mysteries, sure, but Poe created the archetype of the hyper-rational investigator in C. Auguste Dupin. He called these stories "tales of ratiocination." Basically, he wanted to show off how the human mind could deconstruct chaos. Without Poe’s complete works, we don't get Sherlock Holmes. We don't get True Detective. We don't get the entire true crime obsession that dominates Netflix today. It’s all right there in his 19th-century prose.

Then there’s the poetry. It isn’t just about sadness. It’s about the mathematical precision of sound. Poe famously wrote an essay called "The Philosophy of Composition" where he claimed he wrote "The Raven" like a math problem. He decided on the effect he wanted first—melancholy—and then worked backward to find the length, the setting, and that "Nevermore" refrain. Whether he actually did it that way or was just trolling his readers is still debated by experts like Scott Peeples, but it shows his mindset. He wasn't a rambling drunk; he was a craftsman.

The Science Fiction You Didn't Know He Wrote

It’s weird to think of the Gothic king as a sci-fi pioneer, but Edgar Allan Poe the complete works contains The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. It’s his only completed novel.

It starts as a standard sea adventure. Mutiny, shipwrecks, the usual. Then it gets bizarre.

By the end, it’s a surreal, terrifying trip toward the South Pole that feels more like H.P. Lovecraft or a sci-fi fever dream than a 1830s thriller. Jules Verne was so obsessed with it that he actually wrote a sequel decades later. Poe was fascinated by the "Hollow Earth" theory and the emerging science of his day. He wasn't just looking backward at old castles; he was looking at the horizon.

💡 You might also like: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

People often forget about his hoaxes, too. In 1844, he published a news story about a man crossing the Atlantic in a balloon in three days. People bought it. It was a total lie, but Poe’s attention to technical detail was so sharp that he fooled the public. He loved the "con." He loved testing the limits of what people would believe if the "science" sounded right.

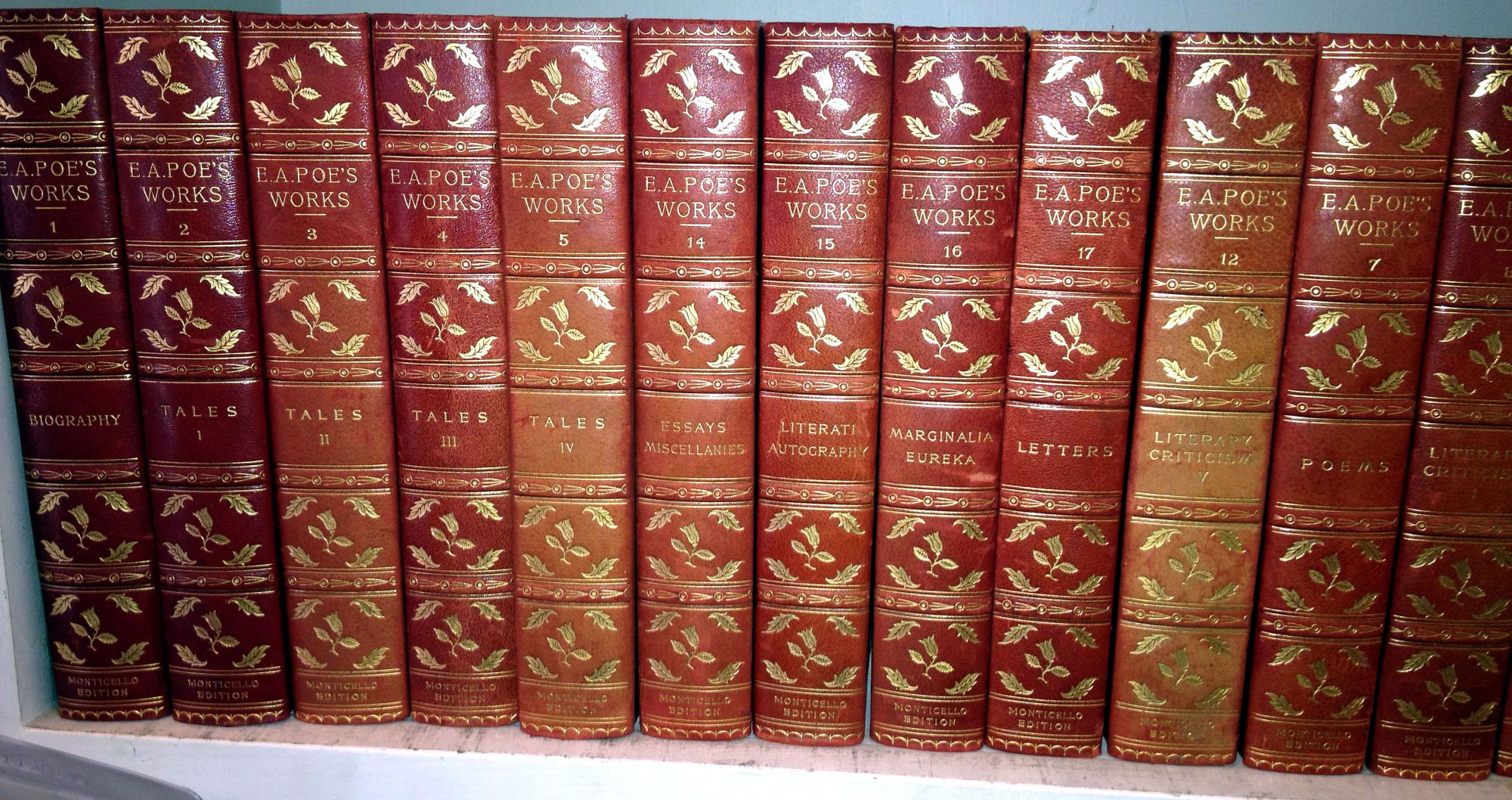

The Problem With Modern Editions

If you’re looking to buy a copy today, you have to be careful. Cheap "complete" editions often leave out the marginalia or the literary criticism. And the criticism is where Poe was at his most vicious. He was known as the "Tomahawk Man" because he would absolutely shred other writers in his reviews. He had a massive feud with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, basically accusing him of plagiarism at every turn.

To get the full picture, you really need a scholarly edition, like the ones produced by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Mabbott spent a lifetime tracking down every comma Poe ever wrote. These volumes are thick, heavy, and expensive, but they show the transition from a young, hopeful poet to a man who was clearly losing his grip on his physical health while his mental sharpess remained terrifyingly intact.

Why We Still Care in 2026

Poe resonates because he understood anxiety before we had a clinical word for it. He didn't write about monsters under the bed; he wrote about the monster inside your own head. The "Tell-Tale Heart" isn't scary because of a dead body; it’s scary because the narrator is trying to convince you he’s sane while he’s clearly unraveling.

That’s a very modern vibe.

📖 Related: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

We live in an era of "unreliable narrators" and psychological thrillers. Poe was the blueprint. When you look at Edgar Allan Poe the complete works, you see a man struggling with the same things we do: the fear of loss, the obsession with "logic" in an illogical world, and the crushing weight of trying to make a living as a creative.

He was paid about $15 for "The Raven." Think about that. One of the most famous poems in the history of the English language, and it barely covered a week’s rent for him. His life was a tragedy, but his work was a triumph of structure over chaos.

Navigating the Darker Corners

If you're going to tackle the full collection, don't do it chronologically. You'll get bogged down in his early, imitative poetry. Instead, bounce around. Read a horror story, then read a "Dupin" mystery, then look at his weirdly beautiful essay on the "Poetic Principle."

Notice the obsession with beautiful women dying. It’s everywhere. Poe lost his mother, his foster mother, and his wife Virginia to tuberculosis. He was surrounded by "the red death" his entire life. When he writes about a "lost Lenore," he isn't just being poetic. He’s processing a lifetime of funerals.

But also, look for the jokes. Seriously. Stories like "The Man That Was Used Up" are satirical. They're biting commentaries on the military and the phoniness of society. He had a sense of humor, even if it was as dark as a cellar in the Inquisition.

How to Actually Read Poe Today

If you want to master the works of Poe without getting lost in 19th-century fluff, follow this path:

- Start with the "Big Three" of Horror: "The Tell-Tale Heart," "The Cask of Amontillado," and "The Masque of the Red Death." These are the purest examples of his "unity of effect" theory.

- Pivot to the Ratiocination: Read "The Murders in the Rue Morgue." It’s long, and the intro is a bit wordy, but pay attention to how he builds the logic. It’s the DNA of every detective show you’ve ever watched.

- The Deep Cuts: Check out "Silence - A Fable" or "The Island of the Fay." These are more atmospheric and prose-poem-like. They show his "art for art's sake" side.

- The Critical Essays: Read "The Philosophy of Composition." Even if you think he's lying about how he wrote, it’s a masterclass in how to think about structure and audience reaction.

- Verify the Source: If you're buying a physical book, look for "Library of America" editions or the Mabbott-edited volumes. Avoid the $2 bargain bin versions that often have typos or missing stanzas.

Poe didn't just write stories; he engineered experiences. He wanted to grab your throat and not let go until the final period. Whether he’s talking about a beating heart or a ticking clock, he’s always reminding us that time is running out. That’s why, nearly two centuries later, we’re still reading him.