History books usually point West. You’ve seen the maps: thick arrows crossing the Atlantic toward the Americas. It’s the story we know best. But honestly, if you look toward the Indian Ocean, there’s another story that lasted much longer and worked quite differently. The East African slave trade, often called the Zanj Rebellion or the Indian Ocean trade, isn't just a "minor" version of the Atlantic one. It was its own complex, brutal, and deeply influential system that stretched from the salt marshes of Iraq to the spice plantations of Zanzibar.

It's messy. It doesn't fit into neat boxes.

Unlike the industrial-scale machinery of the Trans-Atlantic route, this was a network of shifting alliances. It involved Omani sultans, Swahili merchants, and Indian financiers. It predated the arrival of Europeans by centuries and, in some ways, outlasted them.

The Reality of the East African Slave Trade

We need to talk about the scale. Historians like Abdul Sheriff and Edward Alpers have spent decades trying to pin down the numbers. It’s hard. Records weren't always kept like a corporate ledger. Estimates usually land somewhere between 8 million and 17 million people taken from the African interior over a millennium. That’s a massive range. It shows just how much we are still piecing together from oral traditions and fragmented port records in places like Kilwa and Bagamoyo.

Bagamoyo. The name itself basically means "lay down your heart."

🔗 Read more: January 6th Explained: Why This Date Still Defines American Politics

That was the last stop for many before being loaded onto dhows. If you were captured in the interior—maybe near Lake Malawi or the Congo basin—you marched for weeks. Many didn't make it. The ones who did were sold in the markets of Zanzibar. By the 19th century, Zanzibar was the world’s leading producer of cloves. Those cloves required massive amounts of labor. This wasn't just about sending people to distant lands; it was about building a local plantation economy that mirrored what was happening in the Caribbean, just with different crops and different masters.

It wasn't just one "type" of slavery

The Trans-Atlantic trade was almost exclusively about plantation labor. The East African slave trade was more varied, which is why the "human-quality" of the history is so hard to digest. You had people used as domestic servants in households across the Middle East. You had pearl divers in the Persian Gulf. There were even "slave soldiers" who occasionally rose to positions of significant power.

But don't let the "variety" fool you into thinking it was "better."

The Zanj Rebellion of the 9th century proves how grim it was. Thousands of enslaved East Africans working in the horrific salt flats of Southern Iraq rose up against the Abbasid Caliphate. It was one of the largest slave revolts in history. They fought for fifteen years. It basically broke the back of the Caliphate for a while. That kind of desperation only comes from extreme cruelty.

💡 You might also like: Is there a bank holiday today? Why your local branch might be closed on January 12

The Zanzibar Connection and the Omani Shift

In the 1840s, something weird happened. The Sultan of Oman, Seyyid Said, moved his entire capital from Muscat to Zanzibar. Why? Cloves and control. He realized that the East African slave trade was the engine of his wealth. By moving to the island, he could oversee the caravans heading into the interior.

This era changed the geography of Africa.

Caravans led by figures like Tippu Tip (Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab el Murjebi) reached deep into the heart of the continent. Tippu Tip was a merchant, a conqueror, and a slave trader. He became incredibly wealthy, essentially acting as a bridge between the Zanzibari Sultanate and the interior tribes. He represents the uncomfortable reality of the trade: it was often facilitated by local power players who saw an opportunity for profit.

- The caravans didn't just carry people.

- They carried ivory.

- They carried cloth and beads.

- They brought Islam and the Swahili language deep into Central Africa.

The cultural footprint is still there today. If you go to Eastern Congo and hear people speaking Swahili, you’re hearing the linguistic echo of those 19th-century trade routes. It’s a heavy legacy to carry.

📖 Related: Is Pope Leo Homophobic? What Most People Get Wrong

The British Intervention: Politics or Morality?

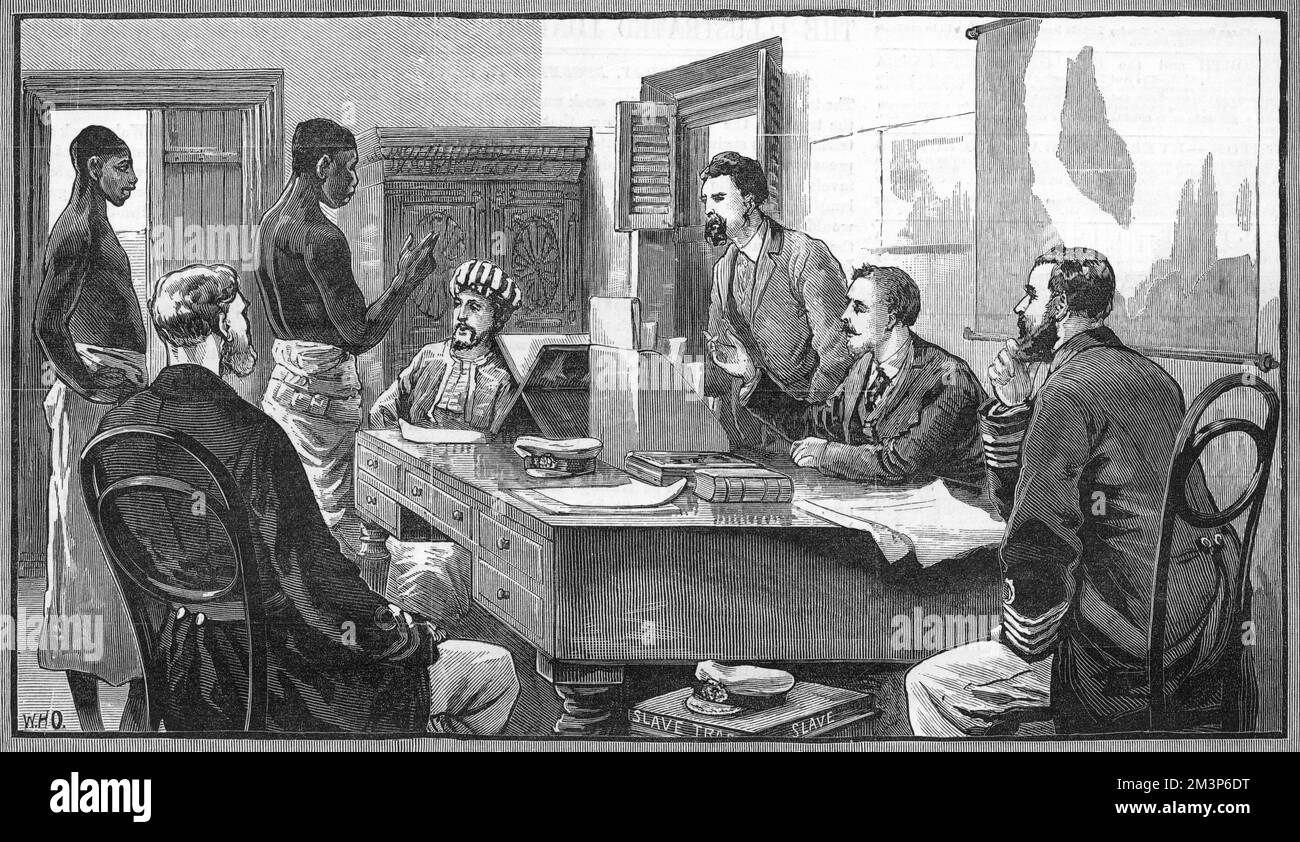

Eventually, the British showed up with their Navy. They wanted the trade stopped.

By the late 1800s, Britain was pressuring the Sultan of Zanzibar to close the slave markets. Was it pure humanitarianism? Kinda. But it was also about colonial dominance. By "ending" the trade, the British gained a moral high ground that allowed them to dismantle the Sultan’s power and eventually establish a protectorate.

In 1873, the Zanzibar slave market was finally closed. A cathedral was built right on top of the old whipping post. It’s a powerful image, but the trade didn't just vanish overnight. It went "underground" or shifted into "forced labor" under different names. Colonialism and the East African slave trade overlapped in ways that are still being studied by scholars at institutions like the University of Dar es Salaam.

Why this matters for your family tree research

If you’re looking into your ancestry and your family comes from the Comoros, Mauritius, or even parts of India (like the Siddis), this history is your history. The African diaspora in the East is huge, yet it gets almost no screen time compared to the Western diaspora.

- The Siddis of India: They are descendants of East Africans who were brought to the subcontinent as soldiers, sailors, and servants.

- The Shirazi identity: Many on the Swahili coast claim Persian descent, partly as a way to distance themselves from the history of enslavement.

- Reunion Island and Mauritius: These islands have deep "Creole" identities forged from the mixing of enslaved East Africans and French settlers.

Actionable Steps for Learning More

History isn't just about reading; it's about seeing where the stories live. If you want to actually understand the East African slave trade, don't just stick to Wikipedia.

- Visit the Sites: If you can, go to Stone Town in Zanzibar. Visit the Anglican Cathedral and the slave cellars. It’s claustrophobic and gut-wrenching, but it makes the history real.

- Read "Empire of the Waves": This isn't a textbook. It’s a look at how the Indian Ocean shaped the world. Also, look for "Lamu: Perspectives on Early Swahili Resource Management."

- Trace the Language: Look at the loanwords in Swahili from Arabic and Persian. It tells the story of who was talking to whom (and who was commanding whom) during those peak trade years.

- Explore the JSTOR Open Archives: Search specifically for "Indian Ocean World Studies." There’s a lot of new research coming out of McGill University that challenges the old "numbers" and looks more at the lived experiences of the enslaved.

The East African slave trade shaped the modern borders, languages, and genetics of an entire third of the globe. Understanding it isn't just a history lesson; it's the only way to make sense of the modern Indian Ocean world. You've got to look at the patterns of the dhows to see where the people went. The past is never really past; it's just waiting for someone to look in the right direction.