History books love a tidy narrative. We’re taught that in 1903, the Wright brothers hopped into a wooden glider in Kitty Hawk, and suddenly, humanity had wings. It’s a clean story. But honestly? It’s also kinda wrong. Aviation didn’t start with a single "eureka" moment on a North Carolina beach. It was a messy, dangerous, and often ridiculous era where early pioneers of aviation were literally jumping off cathedrals and strapping steam engines to oversized kites.

Some died. Most failed. A few changed the world.

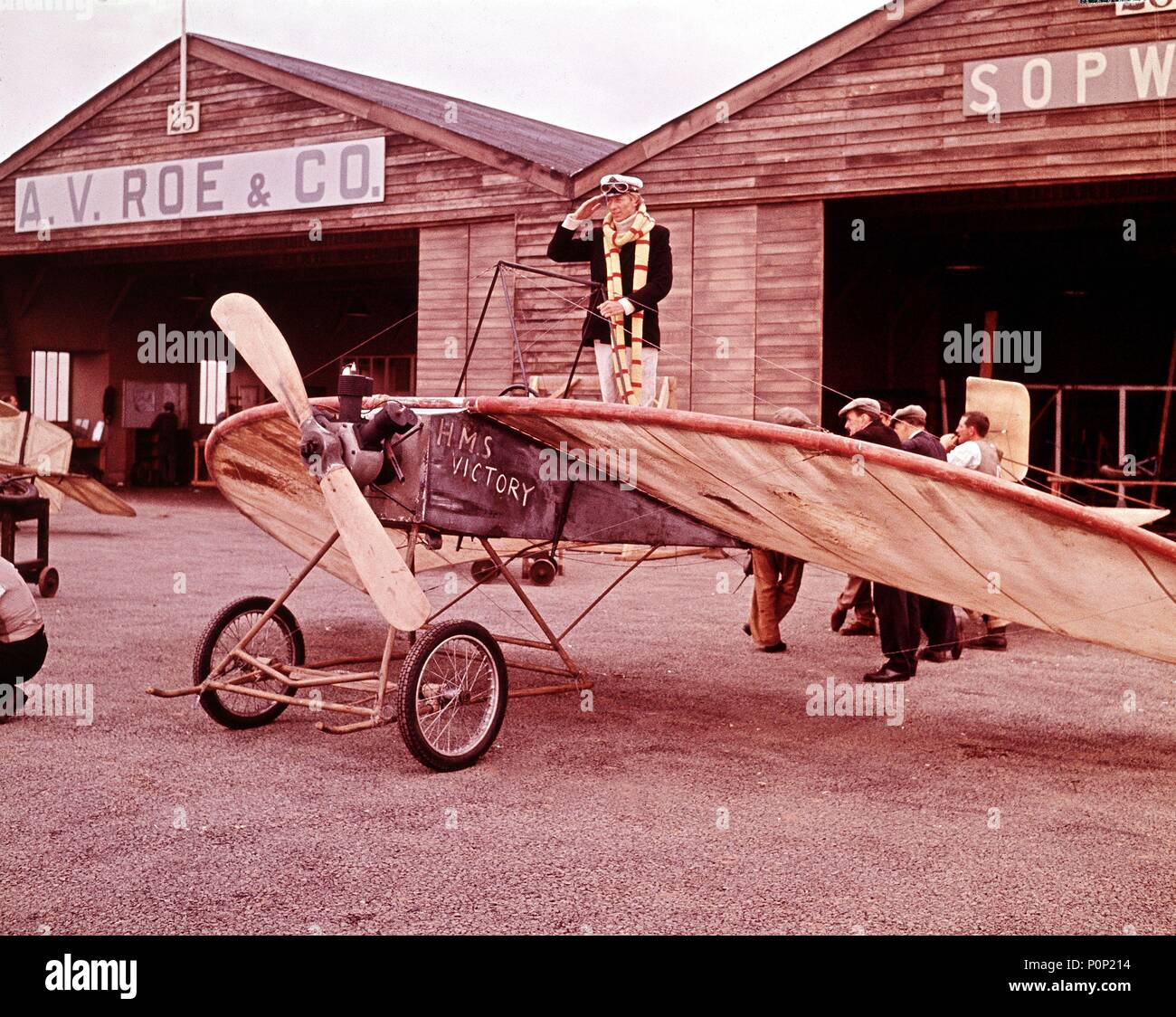

If you look at the decade leading up to the Great War, the sky was full of "men in their flying machines" who weren't just the Wrights. We’re talking about flamboyant Brazilian heirs, stern German engineers, and French cyclists who decided that pedaling on the ground was boring. These people weren't just "inventors" in the way we think of them today. They were daredevils. They were tinkerers who didn't have computer simulations or wind tunnels—they just had wood, wire, and a terrifying amount of audacity.

The Wright Brothers Weren't the Only Game in Town

People get weirdly defensive about the Wrights. Yes, Wilbur and Orville were geniuses. Their 1903 flight was the first controlled, powered, sustained flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft. That's the specific phrasing historians use for a reason. But if you’d been living in Paris in 1906, you probably wouldn't have even heard of them. You’d be shouting for Alberto Santos-Dumont.

Santos-Dumont was a total rockstar.

He was a Brazilian living in France who famously flew his Dirigible No. 6 around the Eiffel Tower to win the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize in 1901. He used to tie his airship to gas lamps outside cafes while he grabbed lunch. Talk about a flex. In 1906, he flew the 14-bis, which looked like a collection of box kites stuck together. For many Europeans at the time, this was the first real flight because it didn't use a catapult launch like the Wrights did initially. It took off under its own power.

The distinction matters. It shows that the "flying machine" wasn't a single invention. It was an evolution. While the Wrights were secretive and obsessed with patents, the European scene was an open-source explosion of ideas.

The Absolute Chaos of Pre-War Design

There was no "standard" look for a plane back then. Everything was experimental. You had monoplanes, biplanes, triplanes, and things that looked like giant venetian blinds.

✨ Don't miss: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

Take Louis Blériot. Before he became the first person to fly across the English Channel in 1909, he was known as the "king of crashes." The guy just kept building and breaking things. His Blériot XI was a masterpiece of simplicity, but it was basically a lawn chair attached to a motorcycle engine and some silk wings. When he finally crossed the Channel, he did it with a leaking engine and a foot injury from a previous accident. He barely made it.

Then you have Glenn Curtiss in the United States. He was a motorcycle racer who realized that if you can make a fast engine, you can make a plane. Curtiss is the reason we have ailerons—those flappy bits on the back of wings that let a plane roll. The Wrights sued him for years over it. They claimed they owned the very concept of lateral control. It was a legal war that nearly grounded American aviation right as World War I was starting.

Honestly, the "flying machine" era was as much about lawyers as it was about pilots.

The Forgotten Monsters of the Sky

- The Maxim Gorky: Not an early pioneer in the 1900s sense, but a massive Soviet experiment later on that showed the limit of these early ideas.

- The Kalinin K-7: A gigantic Russian plane with seven engines and a landing gear so big it had rooms inside it.

- The Caproni Ca.60: An Italian "flying houseboat" with nine wings. Yes, nine. It flew once, reached an altitude of 60 feet, and then broke apart.

Why the "Birdman" Obsession Almost Killed the Industry

Early on, there was this fixation on flapping wings—ornithopters. If birds do it, we should too, right?

George Cayley, an English baronet, was one of the few who realized this was a dead end as early as 1799. He’s the guy who actually figured out the four forces of flight: lift, weight, thrust, and drag. Without Cayley, the men in their flying machines would have just kept trying to flap their way into the dirt. He designed the first real glider that could carry a human, famously forcing his coachman to fly it.

The coachman’s response? "Please, Sir George, I wish to give notice. I was hired to drive, and not to fly."

That quote perfectly sums up the era. The transition from the familiar (horses and carriages) to the terrifyingly new (the sky) was visceral. It wasn't "tech" to them. It was magic, or madness. Usually both.

🔗 Read more: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

The Role of the "Flying Circus" and Public Spectacle

By 1910, flying had become a spectator sport. It was the X-Games of the Edwardian era. Pilots like Harriet Quimby—the first American woman to get a pilot's license—became fashion icons. She flew in a signature purple silk flying suit. People paid huge sums to see these machines at "aviation meets" in places like Reims, France, or Los Angeles.

These meets were where the real engineering happened. If you saw a rival's wing design working better, you went home and copied it. You didn't wait for a peer-reviewed journal. You just got out the wood glue.

It’s worth noting that the "flying machines" were incredibly fragile. We're talking about Grade A spruce, ash wood, and "dope" (a lacquer used to stiffen the fabric wings). If it rained, the wings could warp. If the wind blew more than 15 mph, you stayed on the ground or you died.

The Shift From Hobby to Weapon

Everything changed in 1914.

The "men in their flying machines" were no longer just dreamers or sportsmen; they were soldiers. The romantic era of the gentleman pilot ended the moment someone realized you could drop a grenade out of the cockpit.

Anthony Fokker, a Dutch designer working for the Germans, developed the interrupter gear. This allowed a machine gun to fire through the spinning propeller without hitting the blades. It turned the flying machine from a scout tool into a killing machine. It’s a grim shift, but it’s why aviation tech advanced more between 1914 and 1918 than it had in the previous fifty years.

By the time the war ended, the "rickety kite" phase was over. We had metal fuselages, reliable radial engines, and the birth of commercial mail routes.

💡 You might also like: 1 light year in days: Why our cosmic yardstick is so weirdly massive

What We Get Wrong About Aviation History

If you're looking for the "truth" of this era, stop looking for a single hero.

The early pioneers of aviation were a global network of obsessed weirdos. The Wrights had the best control system. The French had the best engines (the Gnome rotary engine was a beast). The British had the best aerodynamic theory thanks to Lanchester and Cayley.

It was a puzzle where everyone held one piece.

One major misconception is that these planes were "easy" to fly because they were slow. In reality, they were aerodynamic nightmares. Many had "wing warping" instead of ailerons, meaning the pilot had to physically twist the entire wooden wing structure to turn. Imagine driving a car where you have to bend the frame to change lanes. That’s what these guys were doing.

How to Explore This History Yourself

If you actually want to see what these things felt like, don't just look at photos. The photos are static; they don't show the vibration. These engines were loud, they sprayed castor oil everywhere (pilots often had digestive issues because they were inhaling oil mist), and they felt alive.

Practical Steps for History Buffs:

- Visit the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome: Located in New York, they actually fly original and replica aircraft from this era. Seeing a 1910-style engine start up is a sensory assault you won't get from a Wikipedia page.

- Read "Wind, Sand and Stars" by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: While he flew a bit later (the 1920s/30s), his writing captures the soul of what it meant to be alone in a cockpit when "flying machines" were still temperamental beasts.

- Study the "Patent Wars": If you’re into the business side, look up the Wright-Curtiss lawsuits. It’s a fascinating look at how intellectual property can actually slow down human progress.

- Check out the Smithsonian’s digital archives: They have high-res scans of the original 1903 Wright Flyer and the Spirit of St. Louis.

The era of the "flying machine" wasn't just about getting from Point A to Point B. It was the last era of true, unbridled exploration where a person could build something in their garage and change the shape of the world by Tuesday. We don't really have that anymore. Today, if you want to build a plane, you need a billion dollars and a degree from MIT. Back then? You just needed a sturdy engine, some silk, and the willingness to fall from a very great height.

Aviation today is safe, boring, and efficient. But the DNA of every Boeing 787 or SpaceX rocket contains the frantic, oily, and brilliant spirit of those men who first looked at the birds and thought, "Yeah, I can do that."