Most people think John Wayne just walked onto a movie set in 1939, swung a Winchester around his finger in Stagecoach, and became an overnight legend. That’s a nice story. It’s also completely wrong.

Before he was "The Duke," he was Marion Morrison, a prop boy with a busted shoulder and a paycheck that barely covered his rent. Between 1926 and 1939, he starred in dozens of movies that almost nobody talks about today. We’re talking about "Poverty Row" westerns, weird B-movies, and a disastrous 70mm epic that nearly ended his career before it even started. Honestly, if you want to understand why he became the biggest star in the world, you have to look at the ten years he spent being a "nobody."

The Widescreen Disaster of 1930

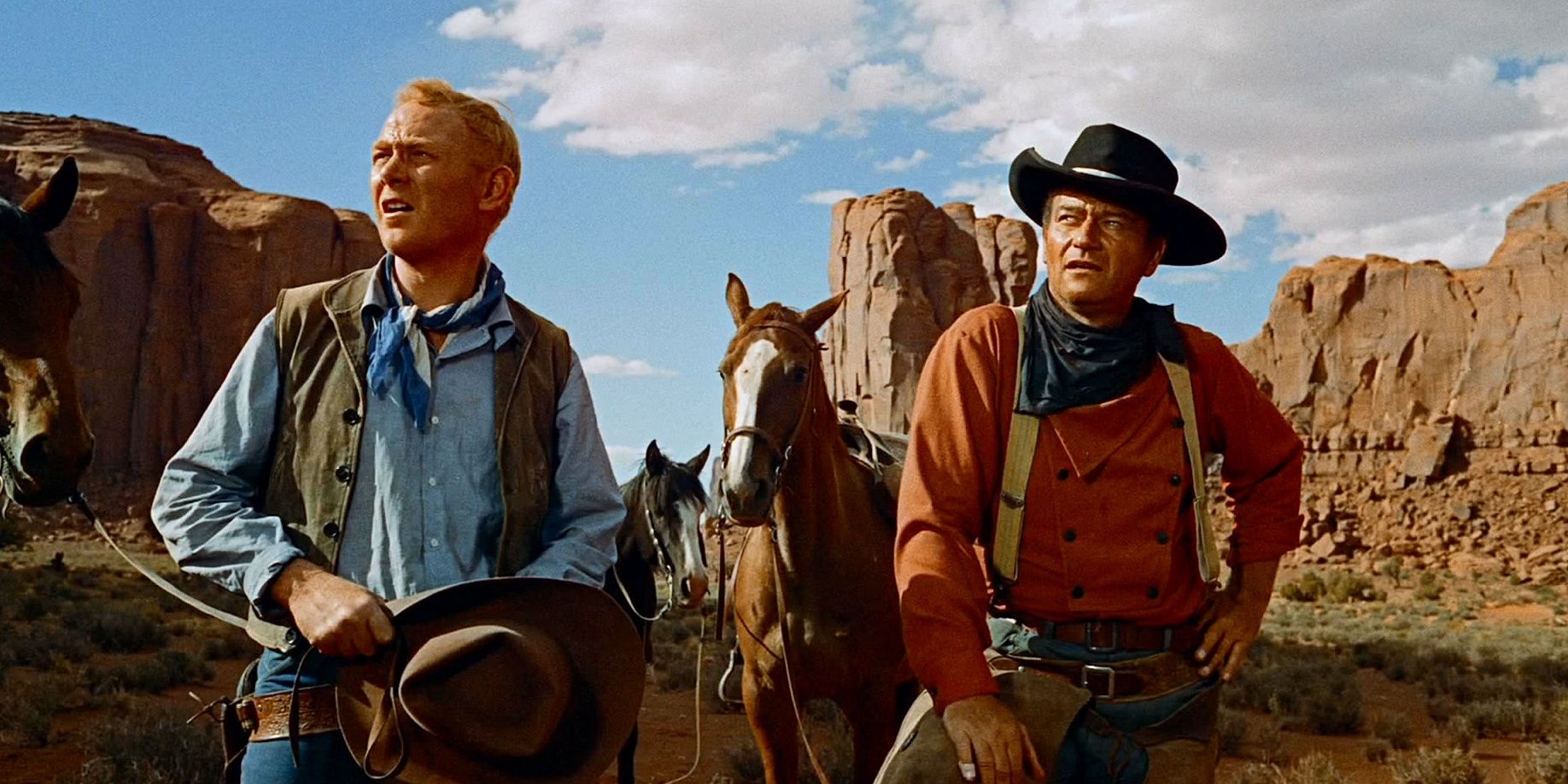

In 1930, a director named Raoul Walsh saw a kid lugging furniture at Fox Studios. He liked the way the kid moved—he had this "careless strength" about him. Walsh gave him a new name, "John Wayne," and cast him as the lead in The Big Trail.

This wasn't just any movie. It was a massive, $2 million experiment shot in "Fox Grandeur," an early 70mm widescreen process. It should have been his big break. It wasn’t.

Most theaters during the Great Depression couldn’t afford the fancy projectors needed to show the widescreen version. The movie bombed. Hard. Fox basically washed their hands of him, and Wayne was relegated to the basement of Hollywood. He went from being the "next big thing" to a guy churning out cheap oaters for tiny studios like Monogram and Lone Star.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Singing Cowboys and Dirty Fighting

You probably didn’t know John Wayne was a singing cowboy. Sorta.

In 1933, he played "Singin' Sandy Saunders" in Riders of Destiny. There was just one tiny problem: Wayne couldn't sing a lick. The studio had to dub his voice with a baritone named Smith Ballew (and later, the director’s son). It was deeply embarrassing for him. Whenever he made public appearances, fans would beg him to sing, and he’d have to awkwardly explain that he couldn't. He hated it so much that he eventually refused to do it anymore, paving the way for a guy named Gene Autry to take over the "singing cowboy" niche.

But while the singing was a bust, Wayne was busy inventing the way movie stars fight.

Back then, movie fights were polite. The hero would wait for the villain to get up before hitting him again. Wayne thought that was ridiculous. Working with legendary stuntman Yakima Canutt, he developed the "no-contact punch" and started throwing chairs, lamps, and anything else he could grab. He wanted to look like a guy who actually wanted to win a fight. You can see the DNA of every modern action movie in those grainy, low-budget 1930s brawls.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

The Three Mesquiteers and the Road to Stardom

By the late 1930s, Wayne was stuck in a loop. He was making movies like The Star Packer and The Telegraph Trail in just a few days. They were "B-movies" in every sense of the word.

He eventually joined a series called The Three Mesquiteers, playing a character named Stony Brooke. It was steady work, but it was a dead end. Or at least, he thought it was. While he was out there in the dust, his old friend John Ford was watching. Ford had been waiting for the right moment—and the right script—to bring Wayne back to the big leagues.

That script was Stagecoach.

When Ford finally cast him as the Ringo Kid, the industry was skeptical. Why hire a "B-western" guy? Ford didn't care. He knew that those ten years on Poverty Row had given Wayne something you couldn't teach: a screen presence that felt earned.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Why These Early Films Matter Now

If you actually sit down and watch something like Winds of the Wasteland (1936), you’ll see the "Duke" persona slowly assembling itself. The walk is there. The slow, deliberate way of speaking is starting to form. He was learning how to hold a camera's attention on a shoestring budget.

Real Talk: How to Watch the "Lost" Wayne

- Skip the "Singin' Sandy" stuff unless you want a good laugh at the dubbing.

- Watch The Big Trail in its restored version. It’s actually a masterpiece of cinematography that was just 25 years ahead of its time.

- Look for the Yakima Canutt stunts. In films like The Lucky Texan, the stunt work is genuinely dangerous and impressive even by today's standards.

The "lost decade" wasn't a waste of time. It was an apprenticeship. Without those 60-plus low-budget films, the John Wayne we know today—the icon of the American West—simply wouldn't exist. He had to fail in 70mm and fake-sing in the desert to figure out who he was supposed to be on screen.

If you’re a film buff, go back and find a copy of Born to the West (1937) or Paradise Canyon (1935). They aren't perfect, but they’re the blueprint for a legend.

Next Step: Look up the 1930 widescreen version of The Big Trail on a streaming service like Max or Tubi to see what John Wayne looked like before the world knew his name.