Let's be real for a second. If you’re looking at e flat melodic minor, you’ve probably hit a wall with the standard natural minor scale. It’s too flat. Too "sad" in a way that feels a bit repetitive. You want something with more teeth.

Most people start their music theory journey with C major, move to A minor, and then eventually stumble into the world of flats. But E-flat is a weird place to hang out. It’s heavy. It’s dense. It’s the key of six flats—or at least it starts that way. When you flip the switch to the melodic minor version, everything changes. You aren't just playing a scale anymore; you're manipulating the very physics of tension and release.

The Actual DNA of E Flat Melodic Minor

So, what is it? Basically, you take your standard E-flat natural minor scale and you sharpen the 6th and 7th degrees on the way up. But here is where most textbooks get annoying. They tell you it always goes back to natural minor on the way down. In the real world—the world of jazz, film scoring, and actual composition—that isn't always true. We call that the "Classical" rule. If you're playing Bach, sure, follow the rule. If you're writing a modern lo-fi track or a neo-soul progression, you might stay melodic both ways.

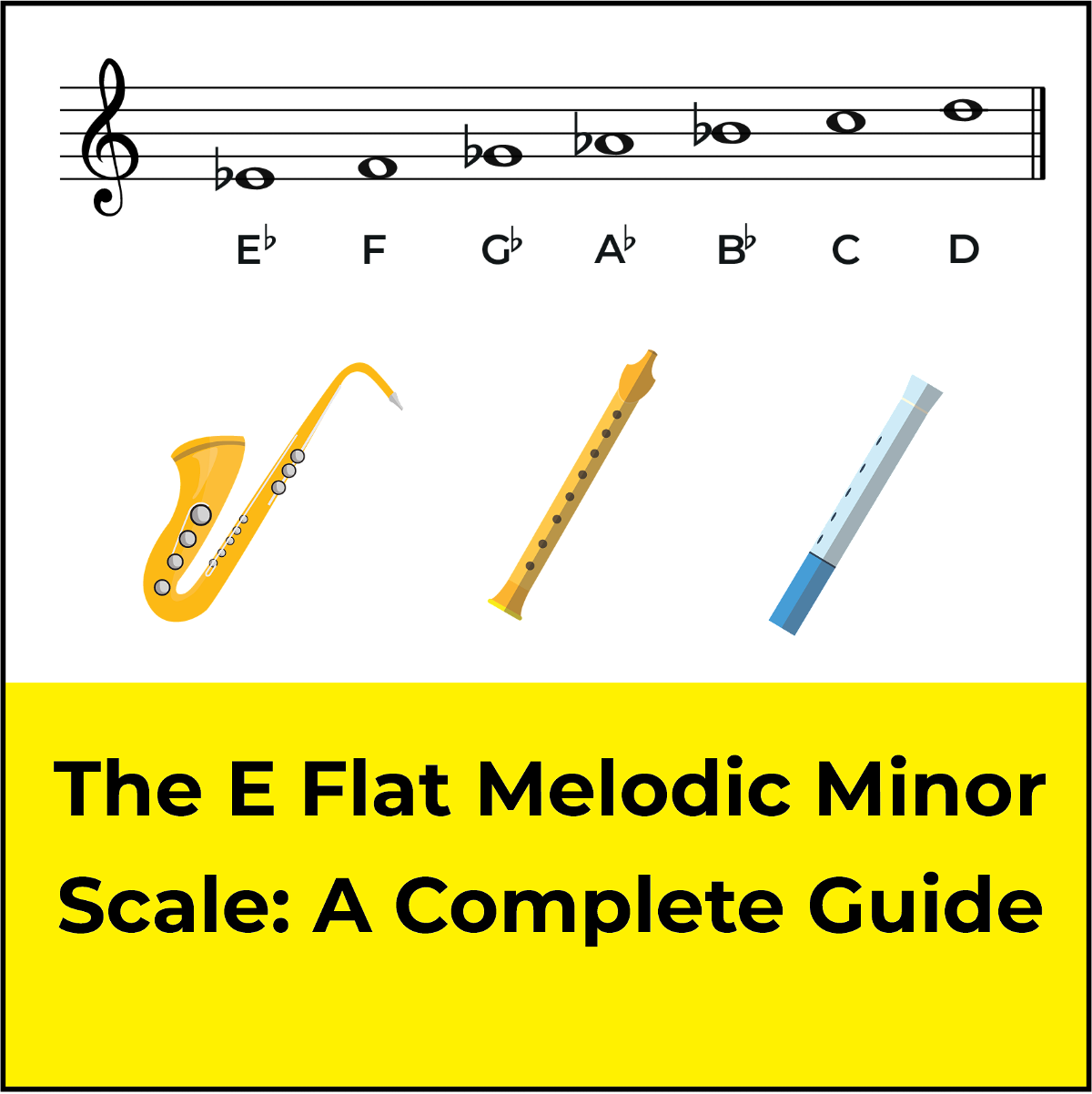

Here are the notes: Eb, F, Gb, Ab, Bb, C, and D.

Notice that C and D? They are natural. In a key signature that is supposed to be drowning in flats, those two natural notes stick out like a sore thumb. That’s the magic. By raising the $Cb$ to $C$ and the $Db$ to $D$, you've effectively removed the "darkness" of the upper tetrachord and replaced it with the bright, leading energy of a major scale. It creates this bizarre, haunting hybrid. It's like a rainy day where the sun suddenly cracks through the clouds, but it's still freezing cold outside.

Why Does This Scale Sound So "Sophisticated"?

It’s about the "Leading Tone." In the natural minor scale ($Eb, F, Gb, Ab, Bb, Cb, Db$), the distance between that $Db$ and the $Eb$ is a whole step. It’s lazy. It doesn’t want to go home. But in e flat melodic minor, that $D$ natural is only a half-step away from the tonic. It pulls you. It screams to resolve.

Musicians like Stevie Wonder or Jacob Collier love these kinds of tonal shifts because they allow for "bright" melodies over "dark" bass lines. Think about the chord possibilities. Instead of being stuck with a $Cb$ Major chord, you suddenly have access to a $C$ diminished or even an $Ab$ Major chord (the IV chord) in a minor key. That $Ab$ Major chord is a total vibe. It gives you that "Dorian" flavor but with a much more aggressive pull toward the root note.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Map Map of the United States and Why We Are Still Obsessed With Paper

The Technical Headache: Enharmonic Equivalents

Honestly, the biggest reason people avoid e flat melodic minor isn't the sound—it's the reading. If you're a guitar player, you don't care. You just move your fingers. But for piano players or horn players, E-flat minor is a nightmare of black keys.

Sometimes, composers get lazy and write everything in D-sharp minor instead. Is there a difference? Sonically, no. They are enharmonically the same. But try telling a violin player to read D# minor ($D#, E#, F#, G#, A#, B, C#$) and they might throw their bow at you. E-flat is generally preferred in orchestral settings, but D-sharp pops up in guitar-heavy music because it relates better to the fretboard.

Real World Application: Jazz and Beyond

In jazz theory, specifically the "Chord-Scale System" popularized by educators like Mark Levine, the e flat melodic minor scale is a goldmine. You don't just use it over an Ebm chord.

- The Altered Scale: If you start this scale on its 7th note ($D$), you get the D Altered Scale. This is the "secret sauce" for playing over a $D7$ chord that wants to resolve to $Gm$.

- Lydian Dominant: Start on the 4th note ($Ab$). Now you have an $Ab$ Lydian Dominant scale ($Ab, Bb, C, D, Eb, F, Gb$). It’s that quirky, "Simpsons-esque" sound that works perfectly over dominant chords that aren't resolving.

It’s versatile.

✨ Don't miss: The Real Reason Root Beer Ham Recipe Works (And How to Not Mess It Up)

Most beginners think scales are just ladders you climb up and down. They aren't. They are palettes of color. When you choose e flat melodic minor, you are choosing a palette that includes deep purples (the flats) and neon yellows (the raised 6th and 7th).

Breaking the Rules

You’ve probably heard that the melodic minor "descends as a natural minor." This is the "Classical Melodic Minor." The idea was that the raised notes were only there to lead the ear upward to the tonic. Once you're coming back down, you don't need that tension anymore, so you revert to the natural "dark" notes ($Cb$ and $Db$).

But look at "Autumn Leaves" or various Bach pieces. You’ll see composers breaking this "rule" constantly. In modern jazz, we use the "Jazz Minor," which stays raised both ways. Why? Because the harmonic interest lies in those specific intervals. If you change them on the way down, you change the mood of the entire solo.

How to Practice This Without Going Crazy

Don't just run the scale. That’s boring and won't help you write better music. Try this:

- Drone an Eb: Use a synth or a looper to hold a steady Eb note.

- Play the Scale Slowly: Listen to the "rub" of the natural $C$ and $D$ against that low $Eb$.

- Identify the "Avoid" Notes: In this scale, there aren't many. Everything sounds pretty sophisticated.

- Switch to Natural Minor: Mid-phrase, drop the $C$ and $D$ back to $Cb$ and $Db$. Feel that "sink" in your gut? That’s the emotional power of modal shifting.

The Emotional Signature

If E-flat major is "heroic" (think Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony), then e flat melodic minor is the sound of a hero who has seen too much. It’s weary but determined. It’s used heavily in film scores when a character is making a difficult, calculated decision. It’s not "crying in a bedroom" sad; it’s "plotting a heist in the rain" sad.

Moving Forward With E Flat Melodic Minor

Stop thinking about scales as homework.

🔗 Read more: Images from the 1920s: What Most People Get Wrong About the Roaring Decade

Start by re-harmonizing a simple melody you already know. Take "Mary Had a Little Lamb" or whatever is stuck in your head and force it into e flat melodic minor. You'll notice the melody suddenly sounds like it belongs in a French noir film.

The next step is to master the chords derived from this scale. Build a triad on every note. You'll find an $Eb$ minor-major 7th chord ($Eb, Gb, Bb, D$). It’s one of the most dissonant, beautiful chords in existence. Use it as a final chord in a song instead of a plain minor triad. It leaves the listener hanging on a cliff, which is exactly where you want them.

Learn the fingerings on your specific instrument, but don't let the technicality kill the Vibe. Music is about tension. This scale is the king of tension.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Locate the "Money Notes": Focus your practice on the transition between the 5th ($Bb$) and the raised 7th ($D$). That interval is the heart of the scale’s tension.

- Apply to Jazz Minor: Practice the scale ascending and descending without changing the notes to natural minor. This builds the "Jazz" ear.

- Chord Construction: Build a chord starting on the 4th degree ($Ab$). Notice it’s a dominant chord ($Ab, C, Eb, Gb$). Practice using this $Ab7$ in place of a standard minor iv chord to see how it brightens your progressions.