You’ve seen them on Instagram. Or maybe scrawled in a high school yearbook. They look like a mess of spilled ink, lowercase letters, and parentheses that don't seem to close. People think e e cummings poems are just about a guy who hated his shift key. Honestly? That's the least interesting thing about him.

Edward Estlin Cummings wasn't just some quirky modernist. He was a painter. He was a prisoner of war. He was a man who looked at a sunset and decided that the word "sunset" was too boring to be used in a straight line. If you think his work is just "cute" or "random," you're missing the visceral, often aggressive beauty of what he was actually trying to do. He was hacking the English language before computers even existed.

The Myth of the "Small Letter" Guy

Most people call him e e cummings. Lowercase. No periods.

But here’s a weird fact: he didn't always insist on it. While his publishers loved the branding of the lowercase name, Cummings himself often signed his name with capital letters in personal correspondence. The lowercase thing wasn't just a gimmick; it was a philosophy. He believed the "I" should be small because the individual is small in the face of nature and love. It’s a bit humbling, right?

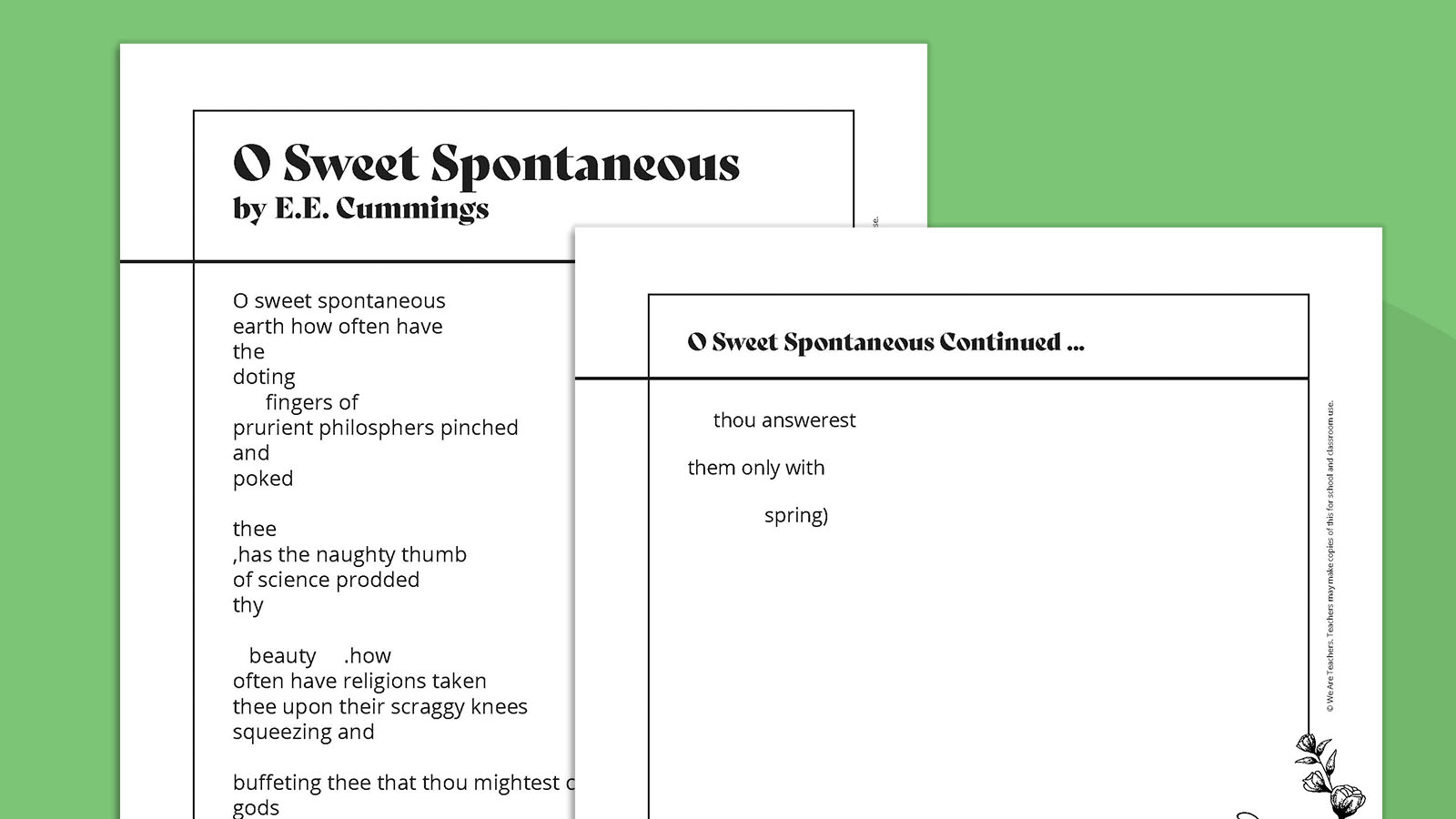

His poems, like "l(a," are basically visual puzzles.

l(a le af fa ll s one l iness

Look at that. It’s the word "loneliness" with "a leaf falls" tucked inside it. He literally shows you the leaf falling through the word. It's not just a poem; it's a painting made of letters. You can't just read that aloud and get the full effect. You have to see it. That’s why e e cummings poems are so hard to teach in a standard classroom—they break the rules of how we process information.

Love, Sex, and the Stuff Teachers Skip

We usually get the "sweet" Cummings in school. "i carry your heart with me(i carry it in" is a wedding staple. It’s beautiful. It’s tender. It’s also just one side of a very complicated, often raunchy coin.

Cummings wrote about sex. A lot.

💡 You might also like: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Take "i like my body when it is with your." It is explicit. It is joyful. It treats the human body like a playground. He wasn't interested in the Victorian stuffiness that still clung to poetry in the early 20th century. He wanted the grit. He wanted the "howl."

He also wrote "she being Brand / -new," which uses the metaphor of a new car to describe... well, a first sexual encounter. It’s funny, it’s rhythmic, and it’s deeply observational. He catches those tiny, awkward human moments that most "great" poets thought were too beneath them to mention. He lived in Greenwich Village during its heyday. He was surrounded by jazz, booze, and avant-garde art. His work reflects that chaotic energy. It isn’t always pretty. Sometimes it’s loud and annoying, just like the city.

Why the Syntax is Actually Genius

You might think he was just bad at grammar.

Wrong.

He was a Harvard grad. He knew the rules perfectly. He just realized that if you break a word in half, you force the reader to slow down. If you put a period in the middle of a sentence, you create a heartbeat.

"pity this busy monster,manunkind,"

Look at that word: manunkind. By smashing "man," "un," and "kind" together, he creates a new concept. It's not just that humans aren't kind; it's that we've become a new, monstrous species of "un-kindness." He was deeply skeptical of progress, technology, and "mostpeople" (his word for the unthinking masses). He saw the world becoming more robotic and used his fractured syntax to stay human.

The Structure of Feeling

Sometimes he uses parentheses to show two things happening at once. It’s like a split-screen in a movie. In "anyone lived in a pretty how town," he tracks the lives of "anyone" and "noone" (two characters) against the passing of seasons.

📖 Related: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

- The passing of time: "spring summer autumn winter"

- The indifference of the world: "sun moon stars rain"

- The rhythm of life: "he sang his didn't he danced his did."

It sounds like a nursery rhyme, but it’s actually a pretty devastating look at how we live and die without anyone noticing. It’s depressing. It’s also gorgeous. He uses these repetitions to mimic the way life actually feels—a lot of the same thing over and over, until suddenly, it’s not.

The Political Side Nobody Mentions

Cummings served as an ambulance driver in WWI. He ended up in a French detention camp because his friend wrote some "subversive" letters and Cummings refused to snitch. That experience changed him. It gave him a lifelong hatred of bureaucracies, governments, and anyone in a uniform telling you what to do.

"i sing of Olaf glad and big" is one of the most brutal anti-war poems ever written. It’s about a conscientious objector being tortured to death. It’s not "pretty." It’s angry. It uses his signature style to mimic the frantic, desperate energy of someone standing up to a machine.

He wasn't a "soft" poet. He was a fighter. He just used commas as his weapons.

How to Actually Read Him Without Getting a Headache

If you're looking at a page of e e cummings poems and feeling overwhelmed, stop trying to "solve" them.

Read them out loud.

Even with the weird spacing, there is a rhythm. He was obsessed with the way sounds hit the ear.

- Follow the capital letters: Usually, if he does use a capital, it’s for a very specific emphasis.

- Ignore the line breaks first: Read the sentence as if it were prose, then go back and see why he chopped it up.

- Look for the "verbs": He loved turning nouns into verbs and vice versa. It keeps the poem moving.

Think of it like jazz. You don't listen to jazz to find a simple melody you can hum along to; you listen for the syncopation. You listen for the moments where the musician goes off the rails and then somehow finds their way back.

👉 See also: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

The Lasting Legacy of the "Typographical Architect"

So, does he still matter in 2026?

Absolutely. In a world of character limits and emojis, Cummings was the original pioneer of "visual language." He understood that how a word looks on a screen or a page changes what it means.

He influenced everyone from Joni Mitchell to modern Instagram poets (though most of them lack his technical skill). He proved that you can be deeply intellectual and wildly emotional at the same time. He showed us that the "rules" of language are just suggestions.

If you want to dive deeper into e e cummings poems, don't start with a textbook. Grab a copy of 100 Selected Poems and just flip to a random page. Don't look for the meaning. Look for the feeling.

Step-by-Step: Getting the Most Out of Cummings

To really "get" what’s happening in these poems, you have to change your brain's hardware.

- Find a quiet spot. You can't read these while scrolling TikTok. They require a different kind of focus.

- Focus on "pity this busy monster,manunkind." It’s perhaps his most relevant work for our current tech-obsessed era. Look at how he critiques "progress."

- Trace the Parentheses. In his love poems, the text inside the parentheses is often the "internal" thought, while the text outside is the "external" action.

- Check out his paintings. Cummings considered himself as much a painter as a poet. Seeing his sketches helps you understand why he shaped his poems the way he did.

The goal isn't to write a literary thesis. It's to realize that language is plastic. You can stretch it, break it, and melt it down to make something that actually looks like a human heart. That’s the real power of e e cummings poems. They aren't just words; they’re living things.

Start with "Buffalo Bill ’s." It’s short. It’s sharp. It’s about the death of a legend and the "Mister Death" that catches us all. Notice the lack of spaces between words like "onetwothreefourfive." It sounds like a rapid-fire gunshot. Once you hear that, you'll never read a "normal" poem the same way again.

Don't let the lowercase fool you. This was a man who lived at full volume.