You’ve probably seen the headlines. A massive recall on romaine lettuce. A local burger joint shut down. A flurry of news alerts about contaminated flour. Most people hear "E. coli" and immediately think of a nightmare scenario involving a bathroom and a lot of regret. But there’s a massive gap between what people think they know and what an E. coli bacterial infection actually is.

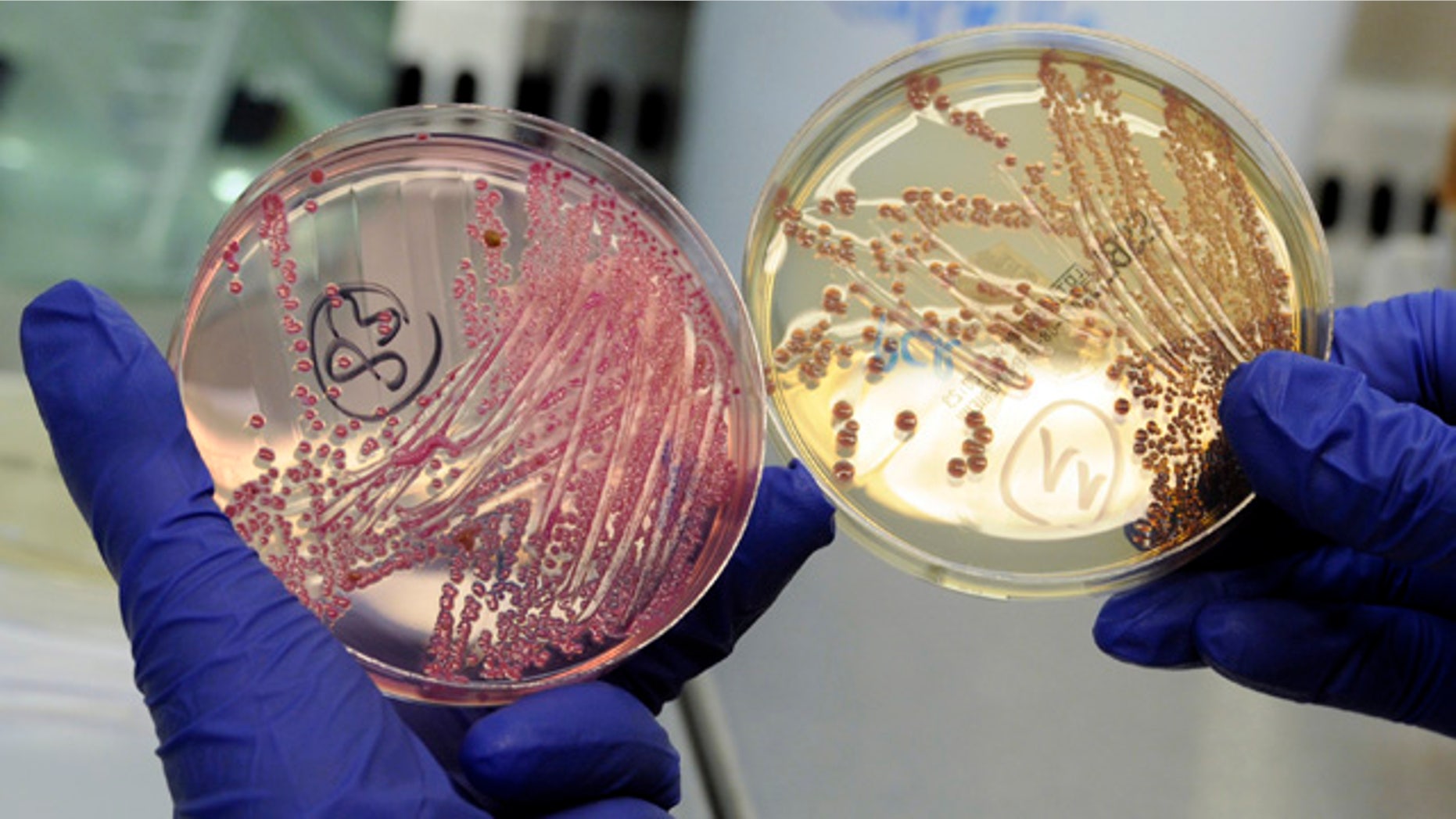

Most E. coli are harmless. Seriously.

Right now, billions of Escherichia coli bacteria are hanging out in your intestines. They’re part of your healthy gut microbiome. They help produce Vitamin K2 and prevent "bad" bacteria from moving in. You need them. But then there are the cousins—the "bad" strains that cause everything from traveler’s diarrhea to life-threatening kidney failure. When we talk about an E. coli bacterial infection, we’re usually talking about these specific, pathogenic troublemakers that have jumped from an animal or contaminated water into your system.

It’s not just about "food poisoning." It’s a complex biological interaction that can vary from a mild tummy ache to a systemic crisis.

The Strains That Actually Matter

If you’re looking for a culprit, start with Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, or STEC. You might have heard it called VTEC or EHEC. Scientists love their acronyms.

The most infamous version is E. coli O157:H7. This is the one that causes the big outbreaks you see on the evening news. Why is it so dangerous? It produces a potent toxin—the Shiga toxin—that damages the lining of your small intestine. This leads to the hallmark symptom: bloody diarrhea.

But it’s not the only one. There’s also ETEC (Enterotoxigenic E. coli), which is the leading cause of traveler's diarrhea. If you’ve ever gone on vacation and spent three days staring at the hotel bathroom tiles, you’ve likely met ETEC. It doesn't usually cause long-term damage, but it’ll certainly ruin a trip to Cabo.

Then there’s EPEC, EAEC, and EIEC. Honestly, the alphabet soup is endless. Each one has a slightly different way of attacking your cells. Some "glue" themselves to your intestinal walls, while others physically invade the cells.

How It Actually Gets Into Your System

It’s gross. Let’s just be honest. It’s the "fecal-oral route." This means, in some way, microscopic amounts of human or animal feces made it into your mouth.

It usually happens because of a breakdown in the food chain. Think about a cow. Cows naturally carry STEC in their guts, and they don't get sick from it. But during the slaughtering process, if things aren't handled perfectly, the bacteria from the gut can get onto the meat. When that meat is ground up for hamburger, the bacteria on the surface gets mixed all the way through.

👉 See also: Why Your Best Kefir Fruit Smoothie Recipe Probably Needs More Fat

This is why a rare steak is usually fine—the heat kills bacteria on the outside—but a rare burger is a gamble.

It’s not just meat, though.

- Leafy greens: Runoff from a cattle farm leaks into an irrigation canal. That water is sprayed onto spinach or lettuce. You eat the salad raw. Boom.

- Unpasteurized milk: The bacteria from the cow's udder or the milking equipment gets into the milk. Without pasteurization (heat), those bacteria stay alive.

- Cross-contamination: You cut raw chicken on a board, give it a quick rinse, then chop your onions.

Water is another big one. Private wells that aren't tested often can become contaminated after a heavy rain. Public pools that aren't properly chlorinated can also be a source, especially if a "fecal accident" occurs. It sounds like a joke from a movie, but it’s a legitimate public health risk.

Spotting the Signs: Is it E. coli or Just a Bug?

Symptoms of an E. coli bacterial infection usually show up three to four days after you’re exposed. However, it can start as early as one day or as late as ten days. It’s sneaky like that.

The primary sign is severe stomach cramps. Not just a little bloating, but the kind of cramps that make you want to curl into a ball. Then comes the diarrhea. It often starts out watery but, with STEC, it can become visibly bloody after a day or two.

You might have a low-grade fever, but it’s rarely a "raging" fever. If you have a temperature over 102°F along with these symptoms, it might actually be something else, like Salmonella or Campylobacter. Nausea and vomiting are common, but the lower GI issues usually take center stage.

Most people get better in about five to seven days. They rest, they hydrate, and their body clears the infection. But for a small percentage—about 5% to 10% of those diagnosed with STEC—things take a dark turn.

The Complication Nobody Wants: HUS

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) is the "big bad" of E. coli complications. It usually hits just as the diarrhea is starting to improve.

The Shiga toxins enter the bloodstream and start destroying red blood cells. These damaged cells then clog the filtering system in the kidneys. This can lead to acute kidney failure. It’s most common in kids under five and the elderly.

✨ Don't miss: Exercises to Get Big Boobs: What Actually Works and the Anatomy Most People Ignore

Signs of HUS include:

- Extreme fatigue.

- Losing color in the cheeks and inside the lower eyelids.

- Decreased urination.

- Unexplained bruises or tiny red spots on the skin.

If this happens, it’s an emergency. Hospitalization is required, and sometimes patients need blood transfusions or kidney dialysis. According to the CDC, most people recover from HUS, but some are left with permanent kidney damage.

The Antibiotic Trap

Here’s a fact that surprises a lot of people: Doctors often avoid giving antibiotics for a suspected E. coli bacterial infection.

Wait, what?

It seems counterintuitive. If you have a bacterial infection, you want a "bacteria killer," right? Not necessarily. With STEC, some studies suggest that antibiotics might actually trigger the bacteria to release more Shiga toxin all at once as they die. This can significantly increase the risk of developing HUS.

Instead, the treatment is mostly supportive. You drink fluids. You rest. You avoid anti-diarrheal meds like Imodium. Why? Because your body is trying to flush the toxins out. If you "stop the flow" with medication, you’re essentially keeping the toxins trapped in your gut for longer.

Basically, you have to let nature take its very unpleasant course.

Real-World Examples: It’s More Common Than You Think

We often think of these infections as "freak accidents," but the data says otherwise. Every year, E. coli causes an estimated 265,000 illnesses and about 100 deaths in the United States alone.

Remember the 1993 Jack in the Box outbreak? It changed everything. Over 700 people got sick, and four children died because of undercooked hamburger patties. It was a watershed moment that led to much stricter USDA inspection rules. Since then, we’ve seen shifts. Today, leafy greens are actually responsible for more outbreaks than ground beef.

🔗 Read more: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

In 2018, there was a massive outbreak linked to romaine lettuce from the Yuma, Arizona, growing region. It sickened 210 people across 36 states. The source? Contaminated canal water used for irrigation. It’s a reminder that even if you’re a strict vegetarian, you aren’t "safe" from a bacterial infection if the supply chain is compromised.

How to Actually Protect Yourself

You can't live in a bubble, and you shouldn't. But you can be smarter about how you handle food.

First, get a meat thermometer. Seriously. Stop guessing if the burger is done by looking at the color. Ground beef needs to hit 160°F ($71^{\circ}C$) to be safe. At that temperature, E. coli is toast.

Second, wash your hands like you mean it. Not a five-second splash. Use soap and scrub after using the bathroom, changing diapers, or touching animals at a petting zoo. Petting zoos are notorious hotspots—goats and sheep carry STEC just like cows do.

Third, be wary of "raw" trends. Raw milk, raw cider, and unpasteurized juices carry a much higher risk profile. Pasteurization exists for a reason; it’s one of the greatest public health triumphs in history.

Finally, wash your produce. While washing won't get rid of all bacteria if it’s "grown into" the leaf, it helps remove surface contamination. Better yet, if there’s a known outbreak, just toss the suspected food. It’s not worth the risk.

Actionable Steps for Recovery

If you suspect you have an E. coli bacterial infection, here is the roadmap:

- Hydrate, but do it right. Don't just chug plain water. Your body is losing electrolytes. Use oral rehydration salts or drinks like Pedialyte.

- Monitor your output. If you notice blood in your stool, call a doctor immediately. Do not wait for it to go away.

- Skip the medicine cabinet. Avoid Ibuprofen (Advil/Motrin) because it can stress the kidneys, which are already at risk during an E. coli infection. Stick to Tylenol if you need pain relief, but check with a professional first.

- Practice strict hygiene. You are contagious. Wash your hands after every bathroom trip and don't prepare food for others until at least 48 hours after your symptoms have completely stopped.

- Get tested. A simple stool sample can confirm if you have E. coli and, more importantly, which strain it is. This helps public health officials track and stop outbreaks before they spread.

The reality is that E. coli is a part of our world. It’s in our guts, our farms, and our food supply. Most of the time, we coexist peacefully. But when the wrong strain gets into the wrong place, it’s a serious medical event. Stay informed, cook your burgers thoroughly, and don't ignore the "bloody" warning signs.