You’ve probably seen them. Those massive, sprawling scenes of peasants getting rowdy at a wedding or the eerily realistic portraits where you can see every single wrinkle on a merchant’s face. It’s Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting. It’s not just "old art." Honestly, it’s the moment when painters stopped obsessing over idealized gods and started looking at the mud, the beer, and the light coming through a dirty window. It changed everything.

Italy had the big, sweeping frescoes of muscular saints. The North? They had oil paint and a strange, almost obsessive need to document exactly what a cabbage looks like.

The Oil Revolution Wasn't Just About Colors

People often think Jan van Eyck invented oil paint. He didn't. That’s a total myth. But he did figure out how to use it in a way that made everyone else look like they were painting with mud. Before this, tempera—egg yolk mixed with pigment—was the standard. It dried fast. You couldn't blend it. It looked flat.

Van Eyck and his contemporaries in the Low Countries started layering translucent glazes of oil. This allowed light to actually pass through the paint layers and reflect off the white ground underneath. It’s why The Ghent Altarpiece looks like it’s glowing from the inside. If you look at the "Adoration of the Mystic Lamb" panel, the sheer variety of botanical life is staggering. Art historians have identified over 40 species of plants in that one work. It wasn’t just "grass." It was specific, identifiable nature.

This shift wasn't just technical; it was a shift in how humans saw their place in the world. In Flanders, the "Renaissance" wasn't a rebirth of Greek and Roman ideals like it was in Florence. It was a rebirth of observation.

Why the "Flemish Primitives" Aren't Actually Primitive

The term "Flemish Primitives" is a bit of a slap in the face. It suggests they were just a warm-up act for the "real" Renaissance. Wrong. These artists—Robert Campin, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling—were sophisticated beyond belief.

Take the Mérode Altarpiece by Campin. It’s a religious scene, the Annunciation, but it’s set in a contemporary 15th-century middle-class living room. You see a copper basin, a pleated towel, and a candle that has just been blown out with a tiny wisp of smoke still curling upward. This is "disguised symbolism." The everyday objects aren't just objects; the basin represents Mary's purity, the smoke represents the moment of the Incarnation. They were hiding the divine in the mundane.

💡 You might also like: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

This was a radical departure.

While the Italians were painting grand, logical spaces using linear perspective, the Flemish were focusing on the "micro-vision." They wanted to show you the texture of velvet, the coldness of steel, and the way a tear sits on a cheek. Rogier van der Weyden was the master of this. In his Descent from the Cross, the emotions are so raw it’s almost uncomfortable. You don't see idealized Greek poses; you see people breaking down in grief. It's human. It's visceral.

Hieronymus Bosch and the Surrealism of the 1500s

Then you have the outlier. The guy who basically predicted Salvador Dalí 400 years early. Hieronymus Bosch.

If you’ve ever stared at The Garden of Earthly Delights, you know the feeling of "What on earth was he on?" But Bosch wasn't just being weird for the sake of it. His work is a deeply moralistic, albeit hallucinogenic, commentary on the follies of man. He used the vernacular of his time—proverbs, folk tales, and religious anxieties—to create these sprawling nightmares.

One of the coolest things about Bosch is that he broke the "rules" of the beautiful, finished surface. If you look closely at his work, the brushstrokes are often visible, almost sketchy. He wasn't interested in the perfect, polished skin of a Van Eyck. He was interested in the chaotic, buzzing energy of sin and redemption.

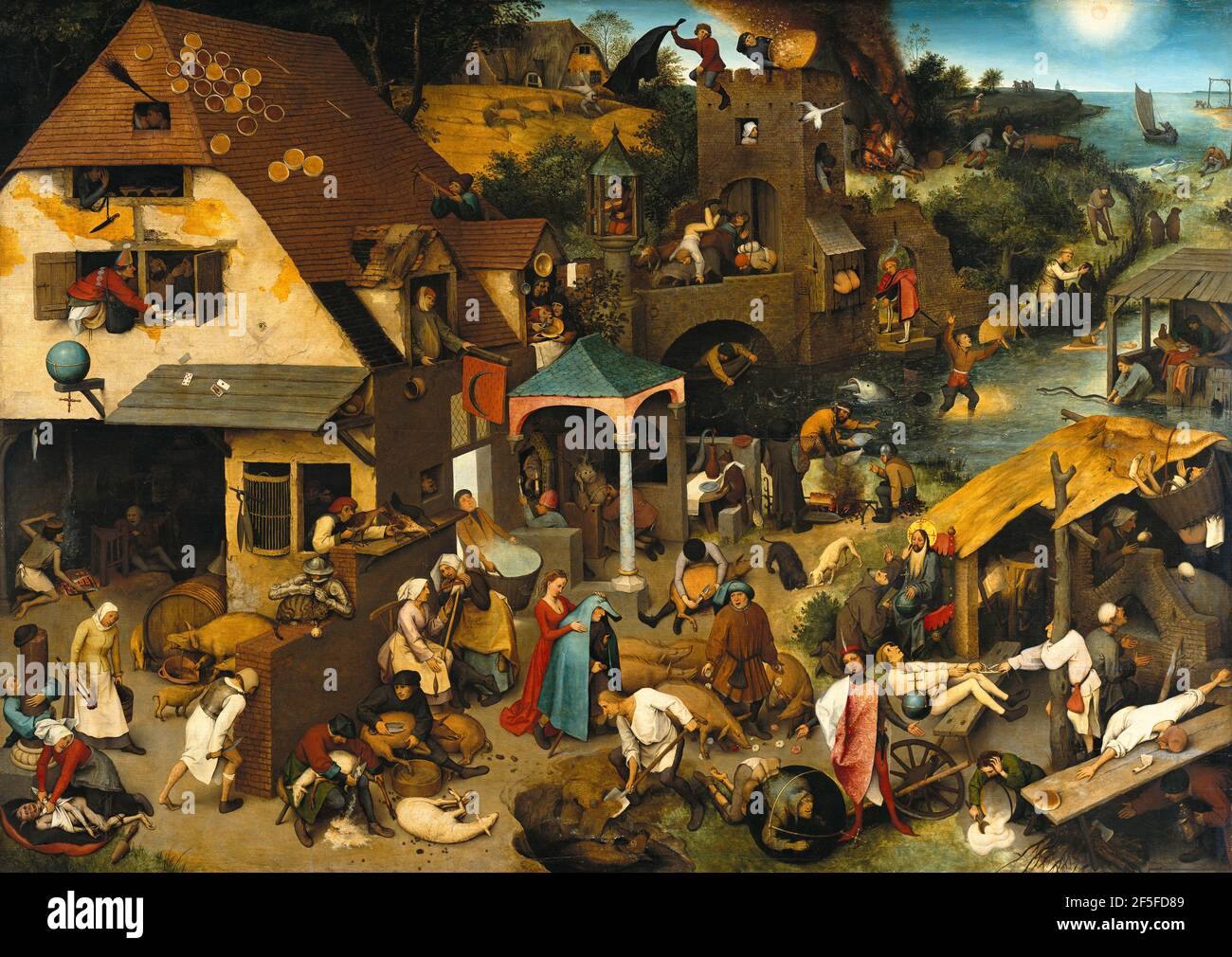

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The King of the Peasant Scene

By the mid-1500s, things changed. The Protestant Reformation was brewing. Religious art was becoming a bit "complicated" because of the whole iconoclasm thing. Enter Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

📖 Related: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Bruegel moved away from the tiny, precious details of the early 1400s and looked at the big picture—literally. He created the "world landscape." His paintings like The Hunters in the Snow aren't just about the hunters. They’re about the vastness of winter, the way the crows sit in the trees, and the tiny figures skating on the ice in the distance.

He’s often called "Peasant Bruegel," which is kind of a misnomer. He was actually a highly educated urbanite living in Brussels and Antwerp. He painted peasants because they represented the "natural" state of humanity, free from the artifice of the court.

- The Harvesters (1565): This is a masterpiece of atmospheric perspective. The way the heat seems to shimmer over the golden fields of wheat is something you usually don't see until the Impressionists.

- The Peasant Wedding: It’s messy. People are eating, dogs are sniffing around, and the bride looks a bit overwhelmed. It’s a slice of life that feels remarkably modern.

The "Dutch" Part: Geography and the Rise of the Middle Class

It’s important to distinguish between "Flemish" (the southern part, mostly Catholic and under Spanish rule) and "Dutch" (the northern part, which eventually became the Dutch Republic). As we move into the late Renaissance and early Baroque, the Dutch started doing something nobody else was: painting for a free market.

In Italy, you painted for a Duke or a Pope. In the Netherlands, you painted for a guy who owned a spice shop or a shipyard. This created a boom in "genre painting"—scenes of everyday life, still lifes, and landscapes.

They weren't looking for God in the clouds anymore. They were looking for the beauty in a peeled lemon or a map hanging on a wall.

Technical Mastery: It’s All in the Optics

There’s a long-standing debate among art historians—most notably sparked by David Hockney and physicist Charles Falco—about whether these artists used optical aids. Did they use a camera obscura or curved mirrors to achieve that insane level of detail?

👉 See also: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

While it’s controversial, it makes sense. The way Jan van Eyck painted the convex mirror in the Arnolfini Portrait shows an incredible understanding of optical distortion. Whether they used lenses or just had superhuman eyes, the result was the same: a level of hyper-realism that wouldn't be challenged until the invention of the camera in the 19th century.

Common Misconceptions About the Northern Renaissance

A lot of people think the Northern Renaissance was just a "lesser" version of the Italian Renaissance. That’s a massive mistake.

- Space: Italians used math to create space (linear perspective). Northerners used light and color (atmospheric perspective). One isn't "better" than the other; they just prioritize different things.

- Subject Matter: It wasn't all religious. Even the religious paintings were secretly about the world around them.

- Anatomy: Critics often say Northern figures look "stiff" compared to Michelangelo's. But Northern artists weren't trying to paint statues. They were painting people in heavy wool clothes in a cold climate.

Why You Should Care Today

This isn't just history. The way we consume images today—the obsession with "high definition," the "aesthetic" of lifestyle photography, the way we document our food—all of that has its roots in Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting. They were the first to say that a simple bowl of fruit or a group of people at a party was worth immortalizing.

They taught us how to see.

Actionable Ways to Experience This Art

If you want to actually understand this, you can't just look at a small screen. You need to see the scale and the texture.

- Visit the "Big Three" Museums: If you're ever in Europe, the Groeningemuseum in Bruges, the KMSKA in Antwerp, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam are non-negotiable. In the US, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has an incredible collection of early Netherlandish works.

- Use a Loupe or Zoom Tool: Many museums now have high-resolution scans of these works online (check out the "Closer to Van Eyck" project). Zoom in until you see the individual hairs on a dog or the reflection of the artist in a drop of water. It will blow your mind.

- Look for the "Easter Eggs": These painters loved hiding things. Next time you see a Dutch still life, look for a fly on the fruit or a skull in the shadows. It’s a "memento mori"—a reminder that life is short and you should probably enjoy that beer while you can.

The Northern Renaissance was the first time art felt "real." It wasn't about the world as it should be; it was about the world as it is. Messy, detailed, and surprisingly beautiful.

Next Steps for Art Lovers

To truly appreciate the depth of this period, your next move should be a deep dive into Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait. Don't just look at the couple; look at the signature on the wall, the individual beads of the rosary, and the tiny scenes of the Passion of Christ carved into the mirror frame.

Alternatively, pick up a copy of Svetlana Alpers' "The Art of Describing." It’s the definitive text on why Dutch art is about seeing rather than narrating. It’ll completely change how you walk through a museum. Finally, if you're into the "weird" side of things, look up the engravings of Pieter Bruegel. They’re often even more chaotic and detailed than his paintings, filled with monsters and social satire that still feels biting today.