You’re probably killing your gains without even realizing it. Most people walk into the gym, grab a pair of 25-pounders, and start flailing their arms like a bird trying to take flight during a hurricane. It looks impressive—sort of—but it does absolutely nothing for your rear deltoids. If you want those "3D shoulders" that look good from the side and back, you have to master the dumbbell bent over raise.

Honestly, it’s a humbling movement. If you do it right, you'll likely have to put down the heavy weights and pick up the "baby" dumbbells. The ones the high schoolers use for curls. It’s annoying. It’s bruising for the ego. But if you want a back that actually looks complete, this is the price of admission.

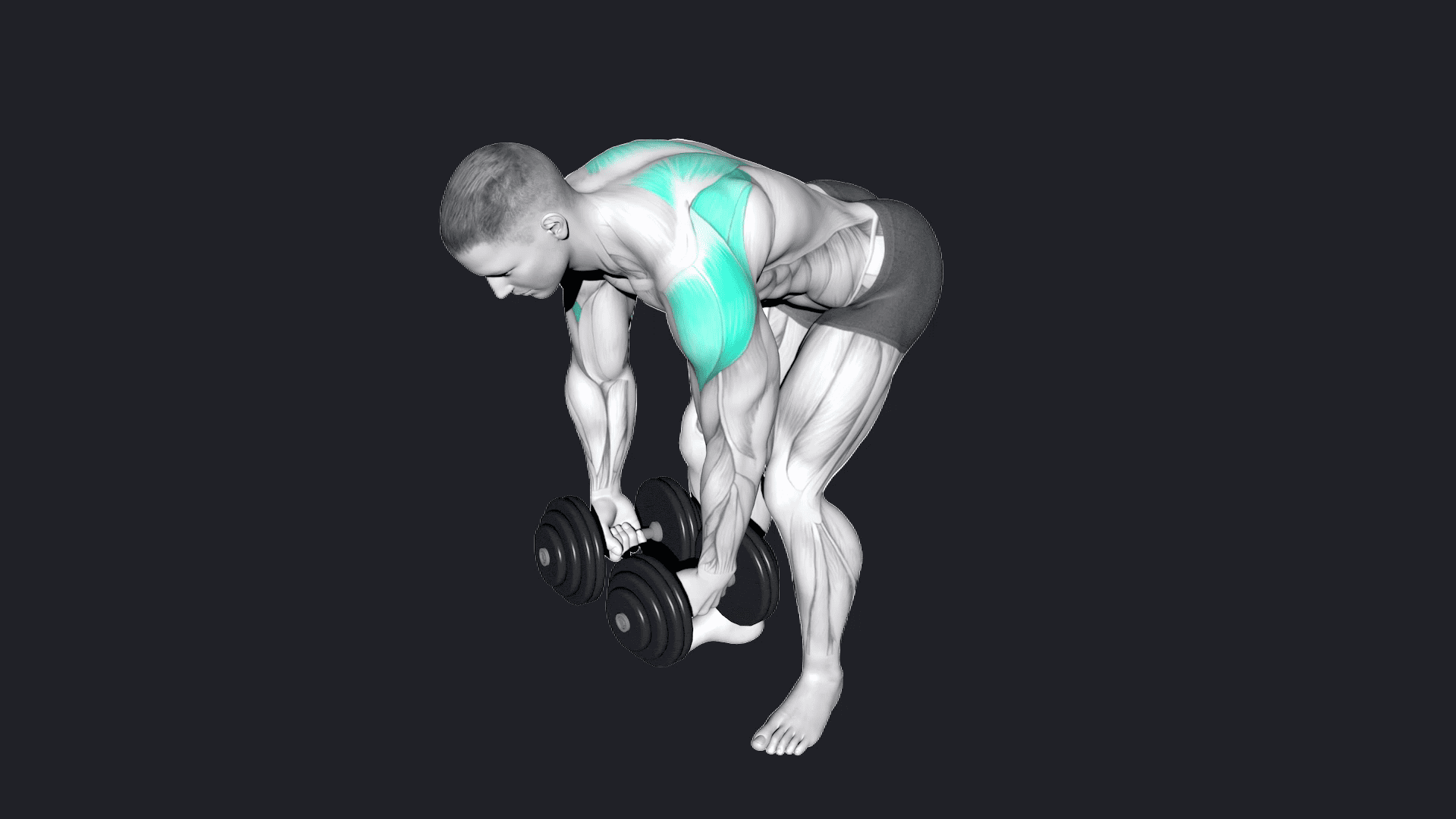

The posterior deltoid is a tiny muscle. Compared to the massive latissimus dorsi or the traps, it’s a pebble. Yet, it's the key to shoulder health and that aesthetic "pop." Most lifters are "front-dominant," meaning their chest and front delts are overdeveloped from too much benching, leading to that rolled-forward, caveman posture. The dumbbell bent over raise fixes that by pulling the shoulders back into a neutral, healthy alignment.

The Mechanics of the Dumbbell Bent Over Raise

Stop thinking about lifting the weight up. Instead, think about pushing the weights out toward the walls. When you focus on "up," your brain instinctively recruits the traps and rhomboids because they are bigger and stronger. They want to take over. They’re bullies. To isolate the rear delt, you need to minimize the movement of your shoulder blades.

📖 Related: Why Drugs Are Bad Mmkay Is Actually Good Advice

Start with your feet shoulder-width apart. Hinge at the hips. You want your torso to be almost parallel to the floor—not standing at a 45-degree angle like you're doing a weird row. Let the dumbbells hang at arm's length with a slight bend in the elbows. This is your starting point. Now, sweep the weights out to the side in a wide arc.

Keep your pinkies high. Seriously. Think about pouring out two pitchers of water as you reach the top of the movement. This slight internal rotation helps engage the posterior fibers specifically. If you lead with your thumbs, you’re just doing a funky lateral raise that hits the side delts instead.

Variations in Grip and Angle

You've got options here. A neutral grip (palms facing each other) is the standard, and it's generally the most comfortable for people with "clicky" shoulders. However, a pronated grip (palms facing the floor) can sometimes provide a better "squeeze" at the peak of the contraction. Try both. See what makes your muscles scream more.

📖 Related: Inner Core Exercises: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Abs

Another pro tip? Do them seated. Sitting at the end of a bench prevents you from using your legs to "cheat" the weight up. When you're standing, it's too easy to use a little hip hinge to get the momentum going. Seated variations force the rear delts to do 100% of the work. It’s significantly harder, which usually means it’s working better.

Why Your Traps Are Stealing Your Gains

This is the biggest mistake in the book. You see it every day. Someone picks up 40s, hunches over, and shrugs the weight up. Their shoulder blades are pinching together like they’re trying to hold a coin between them.

That’s a row. It's a great exercise for the mid-back, but it's not a rear delt raise.

To keep the traps out of it, you have to keep the scapula relatively still. Don't retract your shoulder blades. In fact, keeping them slightly protracted (rounded forward) can actually help isolate the posterior deltoid. You want the movement to happen at the shoulder joint, not the mid-back. If you feel a massive pump in the middle of your spine but nothing on the back of your shoulders, you're doing it wrong. Lower the weight. Focus on the stretch at the bottom and the "reach" at the top.

Scientific Context and Shoulder Longevity

Research, including EMG studies by Dr. Bret Contreras, often shows that the rear delts are most active when the torso is horizontal and the arms move in a plane perpendicular to the body. If you stand too upright, the tension shifts to the lateral deltoid.

The dumbbell bent over raise isn't just about looking good in a tank top; it’s about orthopedic safety. The rotator cuff muscles—specifically the infraspinatus and teres minor—work in tandem with the rear delt to stabilize the humeral head. If these muscles are weak, you’re looking at a future of impingement syndrome or labrum tears.

World-renowned strength coach Charles Poliquin used to emphasize that for every pressing movement you do, you should do two pulling movements. The rear delt raise is a fundamental "pull" that balances the scales. It acts as a brake for your bench press. If you can’t "stop" the weight (eccentric control), your body won't let you "push" more weight (concentric strength) because it perceives a risk of injury.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Looking in the Mirror: Don't crane your neck up to look at yourself. It messes up your spinal alignment. Keep your neck neutral, staring at a spot on the floor about three feet in front of you.

- The "T" vs. the "Y": Aim for a "T" shape. If your arms move forward into a "Y" shape, you’re hitting the traps again.

- Bouncing: If you have to jump to get the weight up, it’s too heavy. Simple as that.

- Short Range of Motion: Bring the weights up until your arms are parallel to the floor. Don't stop halfway.

Programming for Success

You don't need to do these for low reps. You’re not trying to set a 1-rep max on a rear delt raise. That’s a one-way ticket to a strained muscle.

Think high volume. 12 to 20 reps per set. 3 to 4 sets.

The rear delt is composed of a high percentage of slow-twitch muscle fibers, which respond better to longer "time under tension" and metabolic stress. You want to feel the burn. You want that deep, localized ache that makes you want to drop the weights.

Try a "drop set" on your last round. Do 15 reps with your working weight, immediately put them down, grab a pair that’s 5 pounds lighter, and go until failure. The pump is incredible, and the localized blood flow helps with recovery and tendon health.

✨ Don't miss: How Much of a Calorie Deficit Should I Be In? The Math and Reality of Weight Loss

Beyond the Dumbbell: Modern Variations

While the dumbbell is king for accessibility, sometimes the "resistance curve" is a bit wonky. With dumbbells, there’s almost no tension at the bottom and maximum tension at the top.

If you have access to a cable machine, try standing between two pulleys and doing "cross-overs" at shoulder height. The cables provide constant tension throughout the entire range of motion. It’s a different stimulus that complements the dumbbell bent over raise perfectly.

You can also use resistance bands. They actually do the opposite of dumbbells—the tension increases the further you stretch them, which matches the strength curve of the rear delt (which is strongest at the end of the movement).

Actionable Next Steps for Your Next Workout

- Check your weight: Grab a pair of dumbbells that are 5-10 pounds lighter than what you usually use.

- Set the angle: Hinge until your chest is parallel to the ground. If you have a bench, use it for support (chest-supported rows/raises) to take your lower back out of the equation.

- Execute with intent: Perform 3 sets of 15 reps. Focus on "reaching" for the walls and keeping your shoulder blades wide.

- Slow down the negative: Take two full seconds to lower the weights. Don't just let them drop. Gravity is not your workout partner.

- Frequency: Incorporate this at least twice a week. Once on "pull" day and once on "shoulder" day.

Building a complete physique takes time, but the small details—like the rear delts—make the biggest difference in how you actually look and move. Stop ignoring the muscles you can't see in the mirror. Focus on the sweep, control the weight, and watch your posture and strength improve simultaneously.