You're sitting at a red light in a Volkswagen GTI or maybe a fancy Porsche 911. The light turns green. You floor it. Before you've even realized you're moving, the car has slammed into second gear with a crispness that feels like a bolt-action rifle. That's the magic of the dual clutch gearbox. It's fast. Faster than you. Honestly, it’s faster than any human being with a stick shift could ever dream of being.

But then, you’re crawling through heavy traffic on a Tuesday afternoon. The car jerks. It hesitates. It feels like a student driver is learning how to use a clutch for the first time under your hood. This weird Jekyll and Hyde personality is exactly why the dual clutch transmission (DCT) is the most polarizing piece of tech in the automotive world right now.

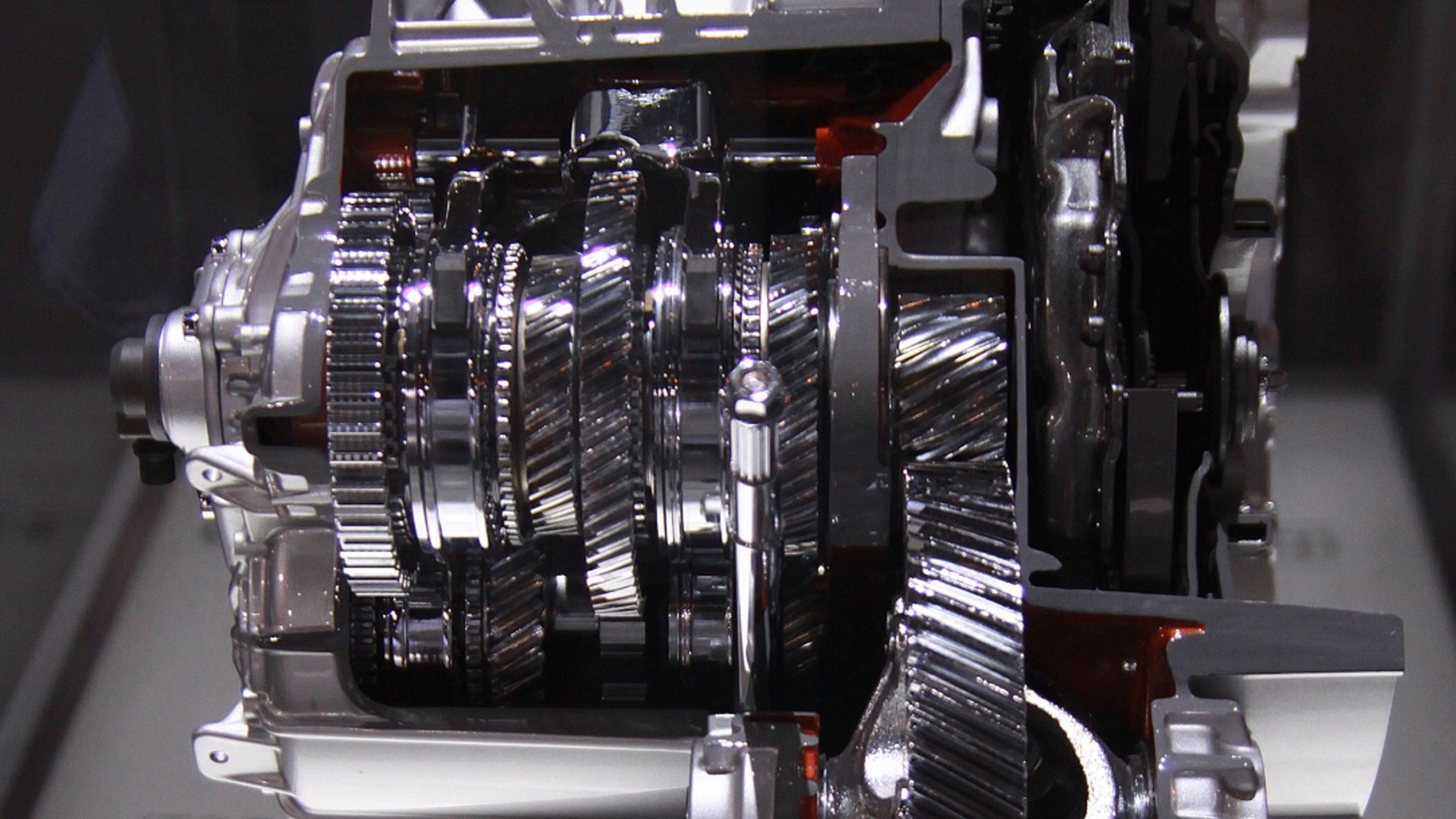

What’s actually happening inside that metal housing?

Basically, a dual clutch gearbox is two manual transmissions shoved into one case, working together like a relay race team. Imagine you have two feet and two pedals, but a computer is doing all the heavy lifting. One clutch handles the odd gears (1, 3, 5, 7) and the other handles the even ones (2, 4, 6).

While you are accelerating in third gear, the computer has already "pre-selected" fourth gear on the other shaft. When it's time to shift, one clutch opens while the other closes simultaneously. The power delivery barely breaks. We are talking about shift times in the range of 8 milliseconds for high-end systems like Porsche’s PDK (Doppelkupplungsgetriebe). To put that in perspective, it takes you about 100 milliseconds just to blink your eyes.

The Wet vs. Dry Debate

If you’ve ever browsed a car forum, you’ve probably seen people arguing about "wet" versus "dry" clutches. It sounds like a laundry setting, but it’s the difference between a reliable daily driver and a mechanical nightmare.

Dry DCTs, like the infamous Ford PowerShift (DPS6) used in Focus and Fiesta models, don't use oil to cool the clutch plates. They’re lighter and more fuel-efficient because there’s no fluid drag. However, they overheat. Fast. In stop-and-go traffic, those plates rub together, get hot, and start to shudder. Ford eventually faced massive class-action lawsuits over this because the "dry" design just couldn't handle the friction of real-world commuting.

👉 See also: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

Wet clutches, on the other hand, are bathed in oil. The oil whisks away the heat. This is what you find in the Volkswagen DSG or the units used by Audi and BMW. They can handle way more torque. They’re smoother. The trade-off? You have to change that expensive fluid every 40,000 miles or so, or the whole thing becomes a very expensive paperweight.

Why Enthusiasts Can't Quit the DCT

Standard torque-converter automatics have gotten really good lately—look at the ZF 8-speed used in everything from Rams to BMWs—but they still feel a bit "rubbery" compared to a dual clutch gearbox.

Because a DCT has a direct mechanical link (clutches instead of a fluid coupling), the connection between your right foot and the tires feels immediate. When you pull a paddle shifter, the car reacts now. There’s no waiting for the engine revs to flare or for the torque converter to lock up. It’s clinical. It’s precise.

The "Clutch Creep" Problem

Here is where most people get frustrated. If you’ve driven a traditional automatic your whole life, you’re used to letting your foot off the brake and having the car "creep" forward smoothly. A dual clutch gearbox has to slip its clutches to mimic this.

If you’re the kind of driver who "inches" forward in traffic every three seconds, you are essentially killing your DCT. You’re making the computer partially engage the clutch over and over, which creates massive heat. To drive a DCT correctly, you kinda have to treat it like a manual. Wait for a gap, let off the brake, and commit to the movement. Don't "ride" the brake pedal.

✨ Don't miss: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

Reliability: The Elephant in the Room

Let's be real. If a standard automatic breaks, it's expensive. If a dual clutch gearbox breaks, you might want to sit down before you see the invoice.

The complexity is the issue. You have a "Mechatronic" unit—which is a fancy word for the brain that controls the hydraulics—sitting inside the transmission. If a sensor fails or a solenoid gets stuck, the car might refuse to go into gear entirely. Repairing these often requires specialized tools that your local neighborhood mechanic might not have. You're usually stuck going to the dealership.

Real-World Examples: The Good and the Bad

- Volkswagen DSG (DQ250/DQ500): Generally considered the gold standard for "normal" cars. If you change the fluid, these things can last 200,000 miles. They're snappy and intuitive.

- Porsche PDK: Widely regarded as the best transmission in existence. Period. It's somehow smooth in traffic and violent on the track.

- Ford PowerShift: A cautionary tale. If you’re looking at a used 2012-2016 Focus, check the service history. Then check it again. Then maybe just buy something else.

- Hyundai/Kia 7-Speed DCT: Found in many T-GDI models. It’s a dry-clutch setup that is "okay" but can get very jerky in hilly terrain or heavy traffic.

The Learning Curve

Your driving style has to change. You can't treat a DCT like a slushbox. For example, if you are decelerating toward a stoplight but it turns green and you suddenly floor it, the dual clutch gearbox might stumble. Why? Because the computer likely had the next "downshift" pre-selected, and you just asked it for an "upshift." It has to scramble to swap gears on the shaft, leading to a second of "nothingness" that can be terrifying when you're trying to merge.

Is the DCT Dying?

Surprisingly, some manufacturers are moving away from them. BMW’s M division recently started swapping DCTs for traditional ZF automatics. Why? Because modern automatics have caught up in speed, can handle more torque for turbocharged engines, and are much smoother for daily driving. The DCT is becoming a niche tool for high-end supercars and specific performance hatches.

How to Keep Your Dual Clutch Alive

If you own a car with a dual clutch gearbox, or you're about to buy one, here is the "cheat sheet" to making it last.

🔗 Read more: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

Stop creeping. In heavy traffic, wait until there is a car-length of space before moving. Don't just let the car roll forward slowly on the brake. You want the clutch to be either "on" or "off," not somewhere in between.

Use Neutral wisely. If you're going to be stopped for three minutes at a train crossing, put it in Park or Neutral. While most modern DCTs are smart enough to disengage the clutches when you hit the brake, it doesn't hurt to reduce the load on the hydraulic system.

Never skip the fluid change. This isn't a "lifetime" fluid situation. If the manual says 40,000 miles, do it at 35,000. The debris from the clutch plates ends up in the oil, and that oil flows through the sensitive Mechatronic valves. Dirty oil is the number one killer of these transmissions.

Launch control is a "sometimes" food. Yes, your car might have a launch control mode that makes you feel like a fighter pilot. Every time you use it, you are putting thousands of miles worth of wear on those clutch packs in about two seconds. Use it sparingly.

Watch for the "death shudder." If the car starts shaking when pulling away from a stop, get it looked at immediately. Often, a software "re-learn" can recalibrate the clutch bite points and save the hardware before it burns out.

Understanding a dual clutch gearbox means accepting its quirks in exchange for its performance. It’s a specialized tool. It’s not as "set it and forget it" as a Honda Civic’s CVT, but for those who love the mechanical connection to the road, there's simply nothing else like it.

Next Steps for Owners

Check your owner's manual right now for the transmission service interval. If you are past the mileage limit or the car is more than five years old on the original fluid, book a service with a shop that specializes in European cars. If you’re shopping for a used car with a DCT, insist on seeing the service records specifically for the transmission fluid—no records usually means a massive repair bill is lurking in your near future.