W.E.B. Du Bois was pissed off when he wrote this. Honestly, that’s the only way to describe the energy behind the 700-plus pages of his 1935 masterpiece. He wasn't just writing a history book; he was staging a full-scale intellectual riot against the Ivy League establishment of the time. For decades, the "Dunning School" of historians—guys at Columbia and Johns Hopkins—had been telling a specific story about the years following the Civil War. They claimed Reconstruction was a disaster because Black people were "ignorant" and "incapable" of self-governance. Du Bois looked at that narrative and decided to tear it limb from limb.

He saw the truth.

Du Bois Black Reconstruction isn't just a chronicle of dates. It's an argument that the American Civil War was actually a general strike. He argues that when half a million enslaved people walked off plantations and toward Union lines, they didn't just "flee." They broke the back of the Southern economy. They forced the hand of a hesitant Abraham Lincoln. They were the central actors in their own liberation, not passive recipients of a "gift" from the North.

The Propaganda of History

The most jarring thing about reading this book today is realizing how long the "official" version of history was just straight-up lies. Du Bois dedicates a whole chapter at the end to what he calls "The Propaganda of History." He lists the textbooks of the early 20th century that depicted the South as a victim and Black legislators as buffoons. It’s wild. These weren't fringe opinions; they were the academic standard.

Du Bois changed the game by shifting the lens. He viewed the era through the eyes of the worker. He saw the struggle of the 1860s and 70s as an unfinished proletarian revolution. He basically asked: What happens when four million people who were treated as property suddenly become citizens?

The answer was a brief, shining moment of radical democracy.

During Reconstruction, Black and white laborers actually worked together in Southern legislatures. They built the first public school systems the South had ever seen. They established hospitals. They tried to fix the roads. It wasn't "corruption" that killed these programs—it was a violent, coordinated counter-revolution by the planter class. Du Bois explains this with a level of economic detail that makes your head spin. He talks about land value, cotton prices, and the "psychological wage" of whiteness.

The Psychological Wage

This is a concept that still haunts us. Du Bois wondered why poor white workers didn't join forces with newly freed Black workers. Logically, they had the same interests. They both wanted better pay and land. But the elite plantocracy offered poor whites a deal: "You might be poor, but at least you aren't Black."

That’s the psychological wage.

It was a fake sense of superiority that cost the white working class actual, tangible power. By choosing racial status over class solidarity, they helped dismantle the very democracy that could have lifted them out of poverty. It’s a bitter pill. Du Bois doesn't sugarcoat it. He shows how this division allowed the old power structures to slide back into place under the guise of "Redemption."

✨ Don't miss: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the General Strike Changed Everything

Most history books say the Emancipation Proclamation was the turning point. Du Bois says it was the "General Strike" of the enslaved. Imagine the scene: thousands of people, without a central leader or a Slack channel, simply deciding to stop working. They didn't need a formal union. They just saw the opportunity and took it.

This drained the Confederacy of its lifeblood.

When those same people joined the Union Army, they brought something the North desperately needed: intelligence. They knew the terrain. They knew where the supplies were. They were the "Black phalanx." Du Bois argues that without this massive internal collapse of the slave system caused by the workers themselves, the North might have settled for a peace treaty that left slavery intact.

It's a massive shift in perspective.

We’re taught that Lincoln "freed the slaves." Du Bois teaches us that the slaves forced Lincoln to free them. It makes the story more complex. It makes it more human. It also makes it much more dangerous to the people who want to keep the status quo.

The Tragedy of the "Splendid Failure"

Du Bois calls Reconstruction a "splendid failure." It’s a weird phrase, right? How can a failure be splendid?

Well, because for a few years, it actually worked.

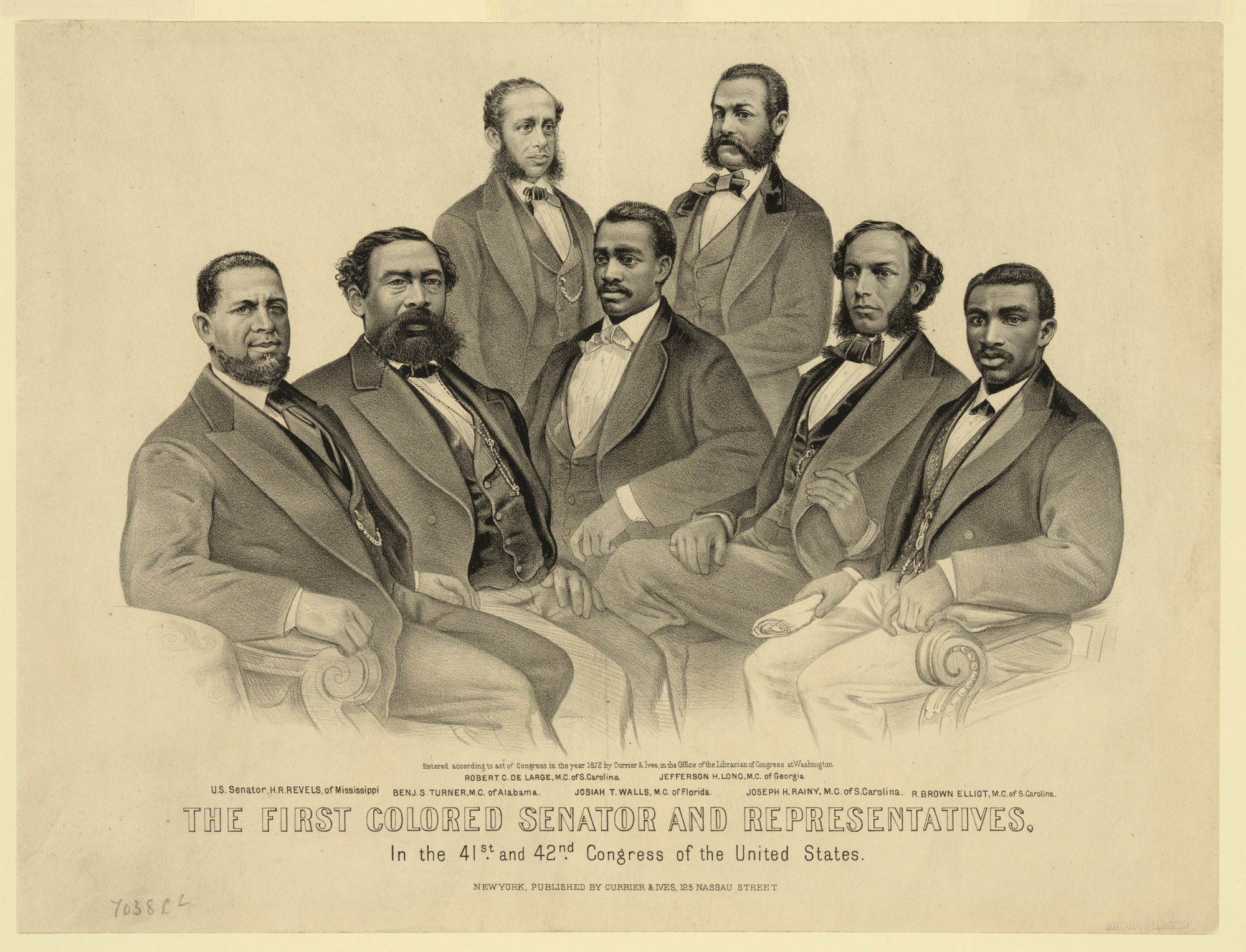

In South Carolina, the legislature was majority Black. Think about that for a second. In a state that had been the heart of the slave power, Black men were passing laws, debating taxes, and funding education. They weren't seeking revenge. They were seeking a functional society. Du Bois meticulously documents the laws they passed. He proves they weren't the "wild spenders" the Dunning School claimed they were. In fact, they were often more fiscally responsible than the white supremacists who replaced them.

But the failure was real.

🔗 Read more: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

The North got bored. The Northern capitalists realized they didn't need a democratic South; they just needed a stable South where they could invest in railroads and factories. So, they made a deal in 1877. They pulled the federal troops out, left the Black population to the mercy of the KKK, and called it a day.

It was a betrayal of epic proportions.

Du Bois tracks the money. He shows how the Northern bankers and Southern planters found common ground in suppressing labor. The tragedy wasn't that Black people couldn't lead; it was that the rest of the country wouldn't let them.

The Legacy of 1935

When Du Bois published this, the "real" historians basically ignored it. The American Historical Review didn't even review it. Can you imagine? One of the most important books of the century, and the gatekeepers just looked the other way.

They couldn't handle the truth.

It took thirty years for the mainstream to catch up. By the 1960s, during the Civil Rights Movement, historians like Eric Foner started looking back at Du Bois's work and realized he was right all along. Today, you can't get a PhD in American history without wrestling with Du Bois. He won the long game.

But the book isn't just for academics.

It's for anyone who looks at the world today and wonders why things are so divided. The roots of our current political mess—the racialized voting patterns, the distrust of public institutions, the weird tension between labor and identity—they are all there in the pages of Du Bois Black Reconstruction. He predicted the path we’re on.

The Real Cost of "Redemption"

When the "Redeemers" took back the South, they didn't just bring back racism. They brought back a system that suppressed everyone. They gutted public spending. They made it harder for anyone to get an education.

💡 You might also like: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

They turned the South into a low-wage colony for Northern capital.

Du Bois shows that the "lost cause" wasn't just about statues and flags. It was a business model. A business model built on the backs of a divided working class. If you understand this, you understand why certain politicians still use the same tactics today. It’s the same playbook, just with better lighting.

What We Can Learn Right Now

Honestly, reading Du Bois is an exercise in humility. It makes you realize how much of what we "know" is just stuff we’ve been told to believe. But it’s also incredibly empowering. It reminds us that history isn't something that happens to people; it’s something people make.

If you want to dive deeper into this, don't just take my word for it. Go get the book. It’s thick. It’s dense. It’s sometimes a little academic. But the prose is electric. Du Bois writes with a poetic fury that you just don't see in modern textbooks.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Reader:

- Read Chapter 14 first. If you’re intimidated by the size of the book, start with "The Counter-Revolution of Property." It’s the heart of his argument about how the elite regained control.

- Look up the Dunning School. Understanding who Du Bois was arguing against makes his points hit much harder. It gives you the context of the intellectual war he was fighting.

- Compare his data to modern census records. Du Bois was a pioneer in using sociology and statistics. You can still see the echoes of the Reconstruction-era "Black Belt" in modern economic maps of the South.

- Challenge the "Great Man" theory. Next time you hear a history of the Civil War that only focuses on generals and presidents, ask yourself where the workers are. Ask what the four million enslaved people were doing while the armies were marching.

- Apply the "Psychological Wage" to today. Look at modern political movements. Are people voting for their economic interests, or are they voting for a sense of status?

Du Bois didn't write this book to be a dusty relic on a shelf. He wrote it to be a weapon. He wanted to arm people with the truth so they could build a better version of democracy. The "splendid failure" of Reconstruction wasn't a final end. It was a blueprint.

It showed us what’s possible when we actually try to live up to the idea of equality. And it showed us exactly how far the powerful will go to stop it.

The struggle he describes isn't over. It just changed clothes. Understanding Du Bois Black Reconstruction is the first step in recognizing the patterns of the present. It’s not just history; it’s a map of the American soul.

The book ends with a call to look at the facts. Not the myths, not the legends, but the cold, hard numbers and the lived experiences of the people on the ground. Only then can we move past the propaganda and start building something real.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Check out Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution. It’s the modern successor to Du Bois’s work and provides updated archival evidence that supports Du Bois’s original thesis.

- Visit the Library of Congress digital archives. Search for "Black Legislators in Reconstruction." Seeing the actual records of these men—many of whom were formerly enslaved—changes your perspective on what was possible in the 1870s.

- Explore the "Black Reconstruction in America" project. Many universities now have dedicated digital humanities sites that map out the economic data Du Bois used, making it much easier to visualize the "General Strike."