History is messy. It’s often written by the people who won the fight, or at least by those who stayed in power long enough to hold the pen. For decades, what happened in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was basically scrubbed from the books. It wasn't just a "riot." That word is doing a lot of heavy lifting for something that was actually a coordinated ethnic cleansing. When we talk about Dreamland and the burning of Black Wall Street, we’re talking about the systematic destruction of the wealthiest Black community in the United States, fueled by a mix of deep-seated jealousy and a single, disputed moment in an elevator.

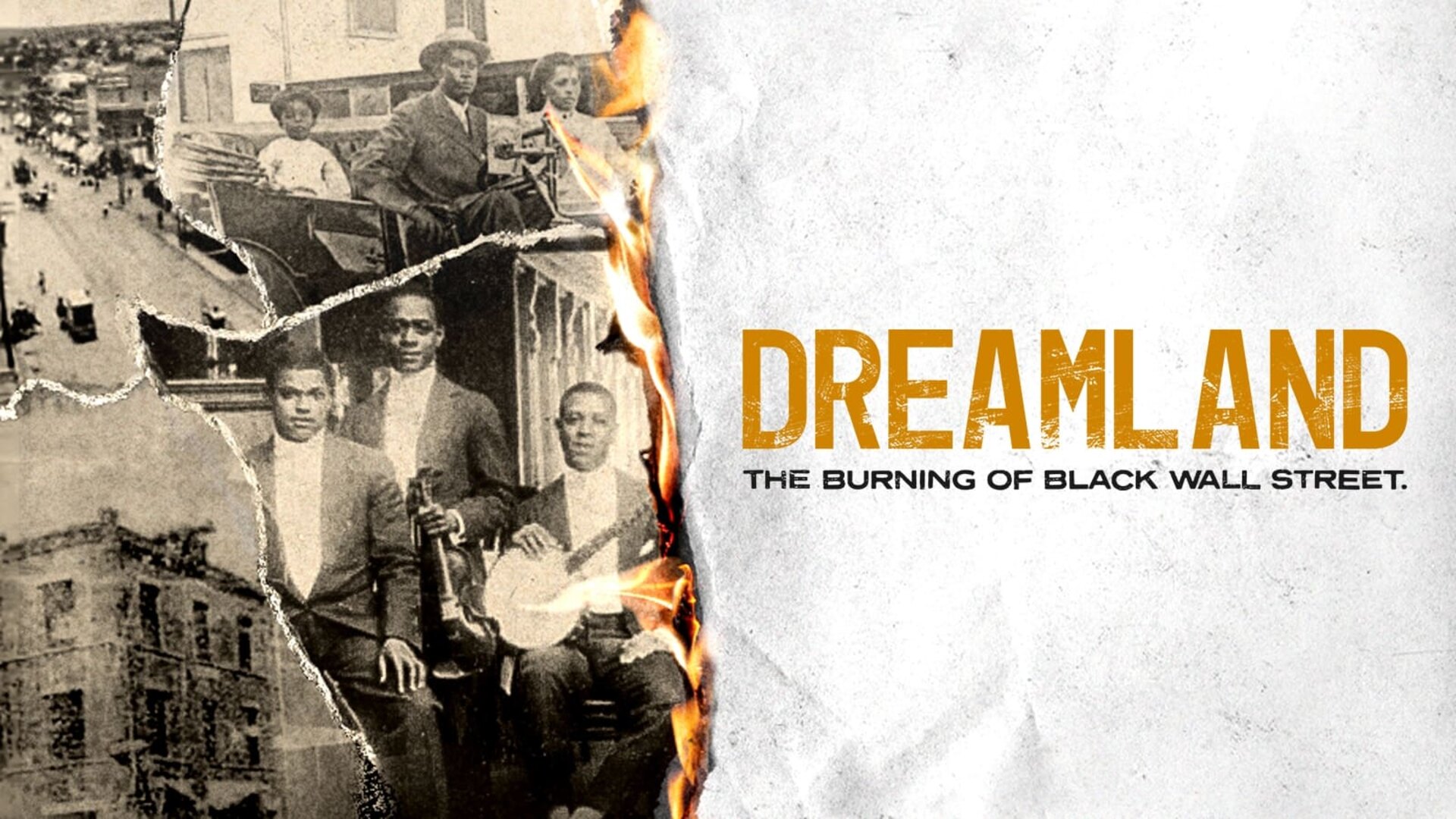

Greenwood wasn't an accident. It was a miracle of economics. Imagine thirty-five square blocks of pure excellence. We're talking about a place where a $5 bill would circulate nineteen times within the community before ever leaving. That kind of internal wealth is unheard of today. You had the Dreamland Theatre, a crown jewel owned by Loula Williams, which sat right in the heart of it all. It was more than a movie house; it was where the community saw itself reflected. Then, in less than twenty-four hours between May 31 and June 1, 1921, it was all ash.

The Spark and the Powder Keg

People like to blame Dick Rowland and Sarah Page. If you look at the old police reports or the sensationalist headlines from the Tulsa Tribune at the time, they framed it as an assault. Rowland, a young Black shoe-shiner, stepped into an elevator with Page, a white operator. He probably tripped. He might have grabbed her arm to steady himself. She screamed. That was it. That was the "justification" used to burn down a literal empire.

But honestly? The elevator was just the excuse. The tension had been simmering for years. You had World War I veterans—Black men who had fought for democracy abroad—coming home to a town that treated them like second-class citizens. They weren't having it anymore. They were proud. They were wearing their uniforms. They had guns, and they knew how to use them. When a white mob gathered at the courthouse to lynch Rowland, the Black men of Greenwood showed up to prevent it. That’s the nuance often lost in the "riot" narrative. It was a defense.

The violence didn't stay at the courthouse. It migrated.

The Destruction of the Dreamland Theatre

If you want to understand the scale of the loss, look at the Williams family. Loula and John Williams were the definition of "Black Excellence" before that was even a hashtag. They owned a confectionery, a primary residence, and the Dreamland Theatre. The theater had 750 seats. In 1921, that was massive. It was the social anchor of Greenwood.

🔗 Read more: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

During the massacre, the theater wasn't just caught in a crossfire. It was targeted.

Eyewitness accounts, many of which were buried for seventy years, describe something terrifying: airplanes. This is a detail that still shocks people who are just learning about this. Private planes were used to drop turpentine bombs and firebombs on the roofs of Greenwood buildings. The Dreamland and the burning of Black Wall Street involved aerial bombardment on American soil against American citizens. Think about that for a second. The Williams family watched their life’s work melt. Loula Williams survived, but the psychological toll of watching your community turn into a war zone is something you don't just "get over."

The Economic Hit That Never Healed

We often focus on the death toll, which is usually estimated between 100 and 300 people, though many historians think it’s much higher. But we need to talk about the money.

- Property Loss: Over 1,200 homes were destroyed.

- Business Wipeout: Every single bank, hotel, and cafe in the district was leveled.

- Insurance Fraud: Here is the kicker. Most insurance companies refused to pay out because they classified the event as a "riot." Since the policies had "riot clauses," the Black business owners were left with literally nothing but the dirt their buildings sat on.

The loss wasn't just $2.7 million in 1921 dollars (which is tens of millions today). It was the loss of generational wealth. If you own a home and a business, you pass that to your kids. Your kids use that equity to go to college or start their own firms. When you burn that down, you’re not just killing people; you’re killing the future. You are resetting the clock to zero for thousands of families while the rest of the city keeps moving forward.

Why "Riot" Is a Lie

The term "Tulsa Race Riot" was used for nearly a century. Even the official commission didn't change the name to "Massacre" until relatively recently. Calling it a riot implies two equal sides fighting in the streets. This wasn't that. It was an invasion.

💡 You might also like: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

The city officials actually deputized the mob. They handed out weapons to white residents and told them to "get a n****r." The National Guard didn't come in to protect the residents of Greenwood. They came in and rounded up the Black survivors, putting them in internment camps. While the Black population was being held at the fairgrounds or the convention hall, their homes were being looted. People reported seeing their own furniture and pianos in the houses of white neighbors weeks later. It was a massive, state-sanctioned theft.

The Resilience of Greenwood

You might think the story ends in 1921. It doesn't. That’s the most wild part. Greenwood actually rebuilt. By the mid-1920s, many of the buildings were back up. The Dreamland Theatre was rebuilt, too. The community refused to die.

However, the second "burning" of Black Wall Street wasn't done with fire; it was done with asphalt. In the 1960s and 70s, urban renewal projects and the construction of I-244 sliced right through the heart of the district. This is a pattern seen across America—highways being used to dismantle thriving minority neighborhoods. The highway did what the fire couldn't—it broke the community's back for good.

Today, if you visit Tulsa, you’ll see the Greenwood Rising museum. It’s a powerful place. But you’ll also see a lot of empty lots and gentrified storefronts. The struggle for reparations is still ongoing. As of 2024 and 2025, the legal battles involving the last living survivors—Lessie Benningfield Randle and Viola Fletcher—have been a rollercoaster of dismissals and appeals. It’s a race against time because these women are over 100 years old.

How to Actually Support the Legacy

Talking about history is fine, but it doesn't pay the bills for the descendants who are still living in the shadow of this event. If you want to honor the memory of the Dreamland and the burning of Black Wall Street, you have to look at the present.

📖 Related: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

First, educate yourself beyond the basics. Read The Ground Breaking by Scott Ellsworth or Unspeakable by Carole Boston Weatherford. These aren't just dry history books; they are investigative works that expose how the city of Tulsa tried to hide the bodies—literally—by burying them in unmarked mass graves like the ones recently investigated at Oaklawn Cemetery.

Second, support the Black-owned businesses that still exist in the Greenwood District. It’s a small footprint now, but it’s there. Spending money in the district is the most direct way to honor the spirit of the original Black Wall Street.

Third, stay informed on the reparations debate. It isn't just about a check; it's about acknowledging a crime. The city has never fully compensated the families for the land and wealth that was stolen under the guise of "civil unrest."

The story of the Dreamland and the burning of Black Wall Street isn't just a tragedy from 100 years ago. It’s a case study in how wealth is built and how easily it can be taken away when the law refuses to protect everyone equally. Greenwood was a proof of concept. It proved that Black Americans could build a self-sustaining, wealthy society despite Jim Crow. The fire didn't happen because Greenwood failed; it happened because Greenwood succeeded too well.

To truly understand this event, one must look at the specific actions to take next. Don't just consume the trauma; engage with the restoration. Support the Greenwood Cultural Center and advocate for the preservation of what remains. Check the local Tulsa legislative updates regarding the 1921 Graves Investigation. Real justice requires more than a memorial; it requires the restoration of what was stolen.

Next Steps for Further Engagement:

- Visit the Greenwood Rising Black Wall Street History Center in Tulsa to see the digitized archives of the original Dreamland Theatre.

- Research the "Greenwood Reconstruction Act" and similar legislative efforts that aim to provide tax incentives for Black-owned businesses in the historic district.

- Audit your own local history. Many cities had "Black Wall Streets" or similar districts that were dismantled by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956; find out what happened to yours.

- Follow the legal updates regarding the survivors' lawsuit through the Justice for Greenwood foundation to stay informed on the current status of the reparations case.