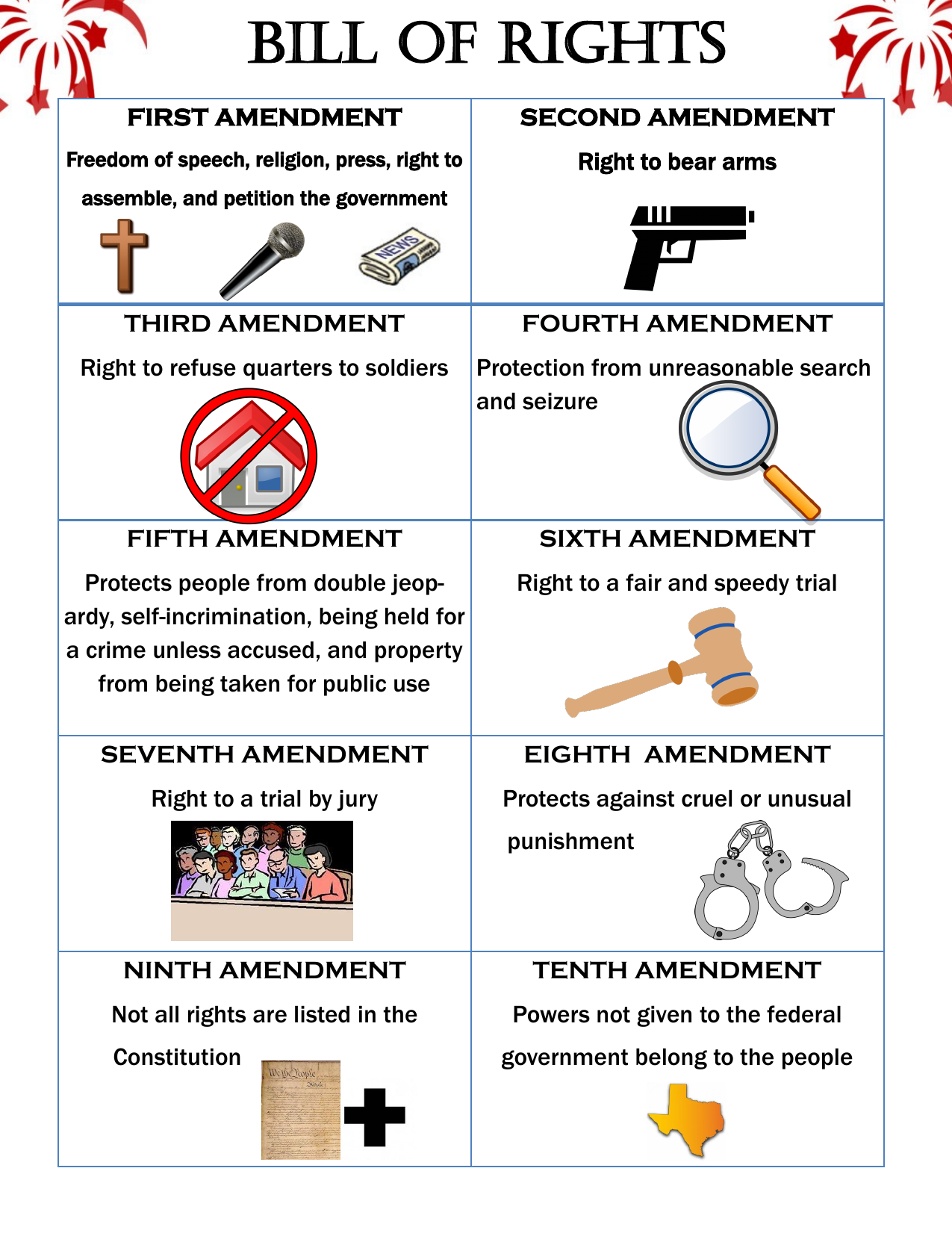

Visualizing the law is hard. Most people, when they think of the Bill of Rights, just see a dusty piece of yellowed parchment with loops of cursive they can barely read. It's distant. It feels like a museum piece rather than a living document. But lately, there's been this massive surge in people looking for drawings of the 10 amendments to help bridge that gap. Whether it’s a middle school teacher trying to keep a class of thirty 13-year-olds from falling asleep or a legal enthusiast trying to simplify complex litigation, these illustrations are popping up everywhere.

Honestly, it makes sense. Humans are visual creatures. We don't think in legalese; we think in symbols. When we talk about the First Amendment, we don't necessarily visualize the words "Congress shall make no law..." Instead, we see a megaphone, a newspaper, or a person standing on a soapbox. These images define our understanding of our own liberties. However, there’s a catch. If the drawing is too simple, it loses the nuance of the law. If it's too complex, it's just a mess of lines.

The Trouble With Drawing Freedom

Visualizing the First Amendment is usually the easy part. You've got five distinct freedoms to play with. Most illustrators use a hand holding a pen for the press or a group of stick figures for assembly. Simple. But what happens when you get to the Third Amendment? How do you draw "no quartering of soldiers" without it looking like a weirdly specific real estate dispute?

The challenge with drawings of the 10 amendments is that they often fall into the trap of being too literal. A literal drawing of the Eighth Amendment might show a pair of handcuffs or a jail cell, but that doesn't actually capture the concept of "cruel and unusual punishment." Is a jail cell cruel? No, it’s standard. The "unusual" part is the legal nuance that a simple sketch often misses.

I remember talking to a graphic designer who was tasked with creating an infographic for a civics non-profit. She spent three days just trying to figure out how to represent the Ninth Amendment. If you aren't a constitutional scholar, the Ninth basically says, "Just because a right isn't listed here doesn't mean you don't have it." How do you draw that? You're essentially trying to illustrate a negative space. She ended up drawing an open box with a question mark—it worked, but it also showed just how much the Bill of Rights relies on abstract thinking rather than concrete objects.

Why We Need Visual Cues for the Bill of Rights

Why does this matter? Because the way we visualize these laws affects how we defend them. If your mental image of the Second Amendment is only a musket, your view on modern firearm legislation might be framed entirely by 18th-century technology. If your drawing of the Fourth Amendment only shows a house, you might forget that it also protects your digital data and your phone.

📖 Related: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

We use these visual metaphors to simplify the world. In education, researchers like Richard Mayer have long talked about the "multimedia principle"—the idea that people learn better from words and pictures than from words alone. In the context of the Constitution, a drawing isn't just "art." It’s a cognitive anchor.

Breaking Down the Visual Language of Liberty

Let's look at how people actually tackle these sketches.

The First Amendment is the heavy hitter. It’s the one everyone wants to draw. You see a lot of symbols of speech—bubbles, microphones, or even a mouth with a "prohibited" sign over it to show what the government can't do. The religious aspect is usually shown with a church or a collection of different religious symbols (the Star of David, a Cross, a Crescent). It’s crowded. There’s a lot going on there.

The Second Amendment is almost always a gun. But the more thoughtful drawings include a silhouette of a "well-regulated militia" in the background. It adds context. It reminds the viewer that the amendment isn't just about an object; it's about a collective and individual right within a specific framework.

The Fourth Amendment usually features a magnifying glass or a police officer standing outside a closed door. This is where modern updates are most needed. If I were drawing this today, I’d probably draw a shield over a smartphone. That's the 21st-century equivalent of "papers and effects."

👉 See also: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

The Fifth and Sixth Amendments get blurry for people. They both deal with the court system. For the Fifth, you often see a person with their hand up—"taking the fifth." For the Sixth, it’s usually a jury box or a lawyer. These drawings help people distinguish between "I don't have to talk" (5th) and "I deserve a fair trial" (6th).

The Artistic Evolution of Constitutional Rights

Historically, we didn't have a lot of drawings of the 10 amendments. In the late 1700s, political cartoons were common, but they were usually satirical and focused on specific politicians like Thomas Jefferson or Alexander Hamilton. They weren't educational guides.

It wasn't until the mid-20th century, particularly around the Bicentennial in 1976, that we saw a push for "civic art." Suddenly, there were posters in every post office showing stylized versions of these rights. These were often very "American Dream" in style—heroic poses, bright colors, very Norman Rockwell.

But things changed. By the 90s and 2000s, the art became more minimalist. We moved away from paintings and toward icons. Look at any modern textbook now. You won't see a detailed oil painting of a courtroom; you'll see a flat-design icon of a gavel. This shift to "iconography" makes the Bill of Rights feel more like a set of tools or a "user manual" for citizenship.

The Misconceptions These Drawings Create

We have to be careful, though. Visuals can lie by omission.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

Take the Seventh Amendment—the right to a jury trial in civil cases. Most people don't even know what this is. A common drawing shows a scale of justice. But that's the same symbol used for the whole judicial system! It doesn't tell you that this amendment is specifically about lawsuits over money or property, not just criminal stuff.

Then there’s the Tenth Amendment. It’s the "States' Rights" amendment. Illustrators usually draw an outline of the United States with lines dividing the states. It looks like a puzzle. But that visualization can be misleading because it suggests a hard separation that doesn't always exist in our federalist system. It doesn't capture the "tug-of-war" between DC and your local state capitol.

Creating Your Own Visual Guide

If you're actually sitting down to create drawings of the 10 amendments, either for a project or just to understand them better, don't just copy what's on Google Images.

First, read the actual text. It’s shorter than you think.

Second, identify the "actor" and the "action." Who is doing what?

Third, think about the "threat." Most of these amendments are about what the government cannot do. Your drawing should reflect that protection.

Instead of drawing a person in jail for the Eighth Amendment, draw a person standing tall while a massive, oversized weight (representing a billion-dollar fine for a minor crime) is held back by a barrier. That’s the "excessive fines" part of the amendment that people always forget.

Actionable Steps for Visual Learners

If you're looking to use these visuals effectively, here is a practical way to approach it.

- Audit your icons: If you're using icons for a presentation, make sure they aren't generic. A "shield" icon is great for the Fourth Amendment, but adding a "Wi-Fi" symbol inside it makes it relevant to today's privacy debates.

- Contrast is key: When drawing the Fifth Amendment, show the contrast between the "Grand Jury" (big group) and the "Double Jeopardy" (two identical clocks or symbols with a big 'X' through one).

- Contextualize the Ninth and Tenth: These are the "power" amendments. Use arrows. Arrows pointing to "The People" for the 9th and arrows pointing to "The States" for the 10th. It visualizes the flow of authority.

- Check your sources: If you’re downloading images, look for those created by non-partisan legal groups like the National Constitution Center or the ACLU. They tend to be more legally accurate than random clip art.

Visualizing the law isn't just about making it pretty. It's about making it accessible. When we can see our rights, we are much more likely to remember them when it actually matters. The next time you see drawings of the 10 amendments, look past the lines and colors. Ask yourself if the image captures the tension between the state and the individual. That's where the real story of the Bill of Rights lives.