You’ve probably been there. You spend three hours meticulously shading a bicep, step back to admire your work, and realize the arm looks like a wet noodle attached to a bag of potatoes. It’s frustrating. Honestly, drawing of human anatomy is the single most humbling hurdle any artist faces. You can draw a tree or a sunset and people will say it looks "artistic" even if it’s messy. But the human brain is hardwired to recognize people. If an eye is two millimeters too low, your viewer’s "uncanny valley" alarm goes off immediately.

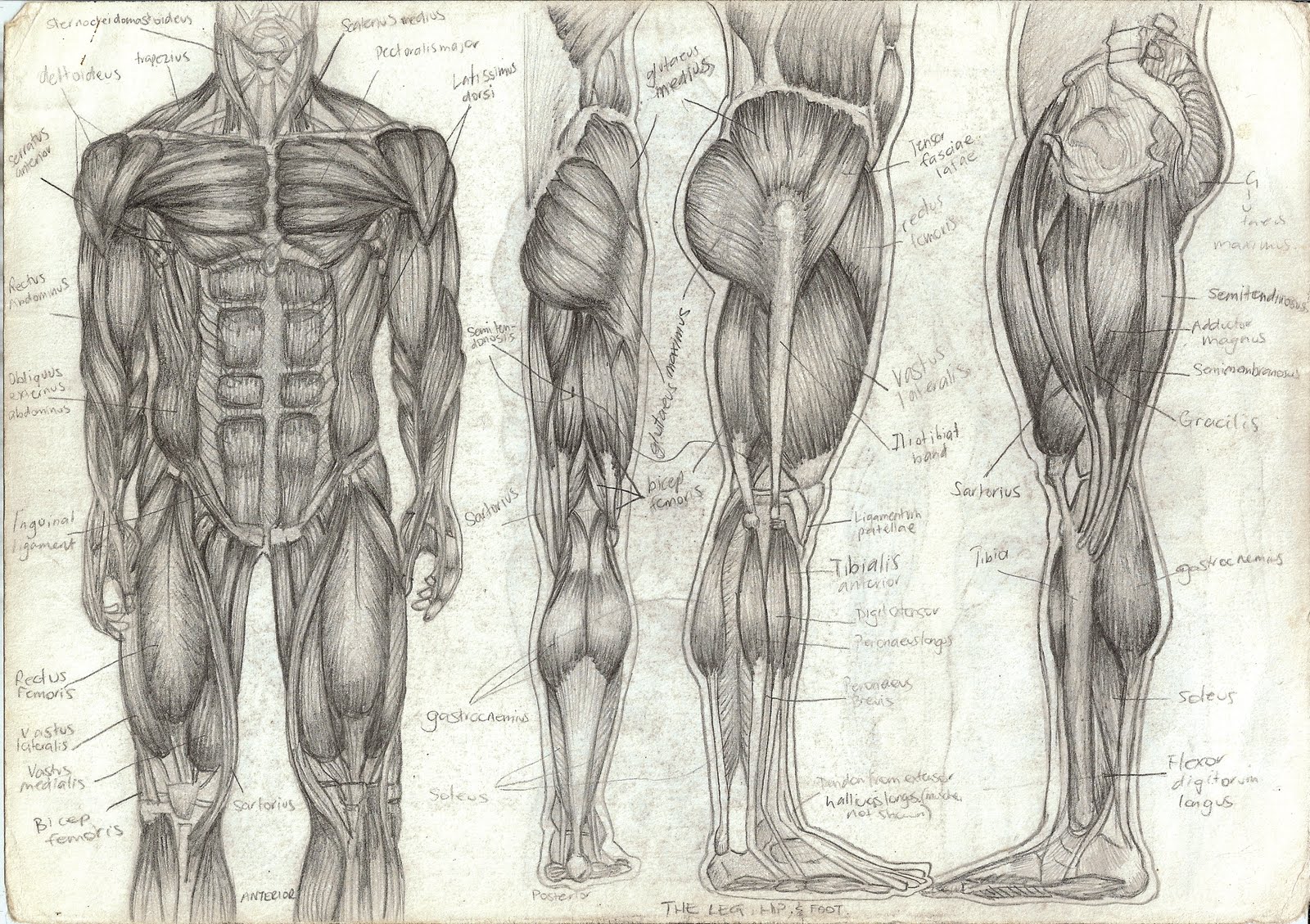

Forget the idea that you need to memorize every single Latin name for every tiny fiber. You don’t need to be a surgeon. You need to be an architect. Most people start with the skin, but the pros start with the bones. If the skeleton is wrong, the muscles have nowhere to sit. If the muscles are wrong, the skin looks like a saggy suit. It’s all layers.

The Bone Trap and Why Proportions Fail

Most beginners learn the "eight heads tall" rule. You know the one: the average human is eight heads high. It’s a fine baseline, but here’s the kicker—almost nobody in real life is actually eight heads tall. Most of us are closer to seven or seven and a half. If you stick rigidly to the "ideal" proportion, your figures will look like Greek statues, which is fine if you're drawing Hercules, but terrible if you're trying to capture a real person at a bus stop.

Andrew Loomis, the legendary illustrator from the mid-20th century, revolutionized how we think about the head. The "Loomis Method" isn't just about a circle; it’s about understanding the skull as a sphere with the sides chopped off. When you’re doing a drawing of human anatomy, the skull dictates everything about the face. If you don't understand that the jaw is a hinge attached to the cranium, your portraits will always look flat.

Look at the ribcage. It’s not a box. It’s an egg. A common mistake is drawing the torso as one solid block. In reality, the ribcage and the pelvis are two solid masses connected by a flexible "accordion" of muscle and spine. When the body twists, those two masses tilt in opposite directions. This is called contrapposto. It’s why statues like Michelangelo’s David look alive while your stiff, front-facing sketches look like wooden mannequins.

Muscles Aren't Balloons

People love drawing muscles. It’s fun. But muscles aren't just lumps under the skin. They are functional pulleys. Take the deltoid (the shoulder muscle). It doesn't just sit on top of the arm. It actually wraps around and inserts into the humerus. If you don't show that "overlap," the arm looks like it’s glued to the side of the chest.

The Mystery of the Forearm

The forearm is arguably the hardest part of any drawing of human anatomy. Why? Because it’s a chaotic mess of twisting muscles. You have the supinator and the pronator muscles that literally cross over each other when you turn your palm down.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

- When the palm is up, the bones (radius and ulna) are parallel.

- When the palm is down, the radius actually crosses over the ulna.

If you don't account for this "twist," your arms will look like sausages. George Bridgman, who taught at the Art Students League of New York for decades, was the master of this. His book Constructive Anatomy focuses on the "blockiness" of these forms. He didn't see a forearm; he saw a series of interlocking wedges. That’s how you should see it too.

The "Gesture" Secret

You can have perfect anatomical knowledge and still produce boring art. This is where gesture comes in. Gesture is the "story" of the pose. It’s the long, sweeping line that goes from the tip of the fingers down to the heel.

Basically, you should be able to capture the essence of a person in 30 seconds. If you spend those 30 seconds drawing an earlobe, you’ve lost the rhythm. Pro artists usually do "gesture drawings" where they focus entirely on the movement before they ever think about where the kneecap goes. It’s about flow.

Why Hands and Feet Ruin Everything

Let’s be real: everyone hates drawing hands. We hide them in pockets or behind backs. But hands are just a series of boxes and cylinders. The palm is a square. The fingers are three-part hinges. The most important thing to remember is the "fan" shape. Fingers don't grow out of the hand like stalks of corn; they radiate from the wrist.

Feet are even worse for some. Most people draw them like flat wedges. But the foot has an arch. It’s a tripod! The weight of the body is distributed between the heel, the base of the big toe, and the base of the little toe. If you understand that tripod, your figures will actually look like they are standing on the ground rather than floating above it.

Light, Shadow, and the Illusion of Volume

Anatomy is nothing without light. You're trying to trick the eye into seeing 3D on a 2D surface. This is where chiaroscuro comes in—the contrast between light and dark.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

When light hits a bicep, it creates a "core shadow," a "reflected light," and a "cast shadow." Many beginners forget reflected light. They think shadows are just black. But shadows are full of bounced light from the floor or other body parts. Adding that tiny sliver of light on the edge of a shadow is what makes a drawing of human anatomy look like it’s popping off the page.

The Impact of Modern Tools

Nowadays, we have 3D posing apps and high-definition photography. These are great, but they can be a trap. Photos "flatten" anatomy. The camera has one lens, but your eyes have two. This is why drawing from a live model is still the gold standard in art schools. A camera doesn't feel the weight of a limb, but a sketcher can. If you can't get to a life-drawing class, use "Proko" or "Line of Action"—sites that provide timed references to keep you from overthinking.

Common Myths That Hold You Back

- Myth 1: You need to know every bone. False. You just need to know the landmarks. The collarbone, the pelvis "points," the spine, and the elbows. These are the spots where the bone is right under the skin.

- Myth 2: Smooth skin looks more realistic. Nope. Real bodies have bumps, tendons, and fat. If you smooth everything out, your drawing looks like a 3D render from 2004.

- Myth 3: Proportions are fixed. Every body is different. A marathon runner’s anatomy looks nothing like a powerlifter’s. Learning the "average" is just a way to know how to break the rules later.

The masters—Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Loomis, Bridgman—all had different styles, but they shared one thing: they studied the "why" of the body. They didn't just draw what they saw; they drew what they understood.

Actionable Steps for Better Anatomy

If you want to stop making your drawings look "off," you need a system. Don't just wing it.

Carry a sketchbook everywhere. Don't draw "pretty" pictures. Do 10-second scribbles of people at the grocery store. Focus on how their weight shifts when they carry bags. That's real anatomy.

Trace the skeleton over photos. Take a magazine or a printed photo of a person and use a red marker to draw the skeleton inside them. This trains your brain to see through the skin. It's like X-ray vision for artists.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Focus on "Landmarks." Next time you draw, find the "bony landmarks" first. Locate the pits of the neck, the acromion process of the shoulder, and the iliac crest of the hip. Connect these points before you draw a single muscle.

Study the "Box" method. Instead of drawing rounded limbs, try drawing the body using only boxes. This helps you understand the perspective and how the body occupies space. If you can draw a box in perspective, you can draw a torso.

Limit your time. Give yourself 2 minutes to draw a full figure. This forces you to ignore the details (like fingernails or hair) and focus on the big shapes—the ribcage, the pelvis, and the flow of the spine.

Flip your canvas. If you're drawing digitally, hit the "flip horizontal" button. If you're on paper, hold it up to a mirror. You will immediately see that the eyes are lopsided or the legs are two different lengths. It’s a brutal but necessary reality check.

Anatomy is a lifelong study. Even the best concept artists for Disney or Marvel still go back to basics. It’s not about being perfect; it’s about making the figure feel like it has weight, breath, and a skeleton underneath. Stop worrying about the "perfect line" and start worrying about the "solid form."