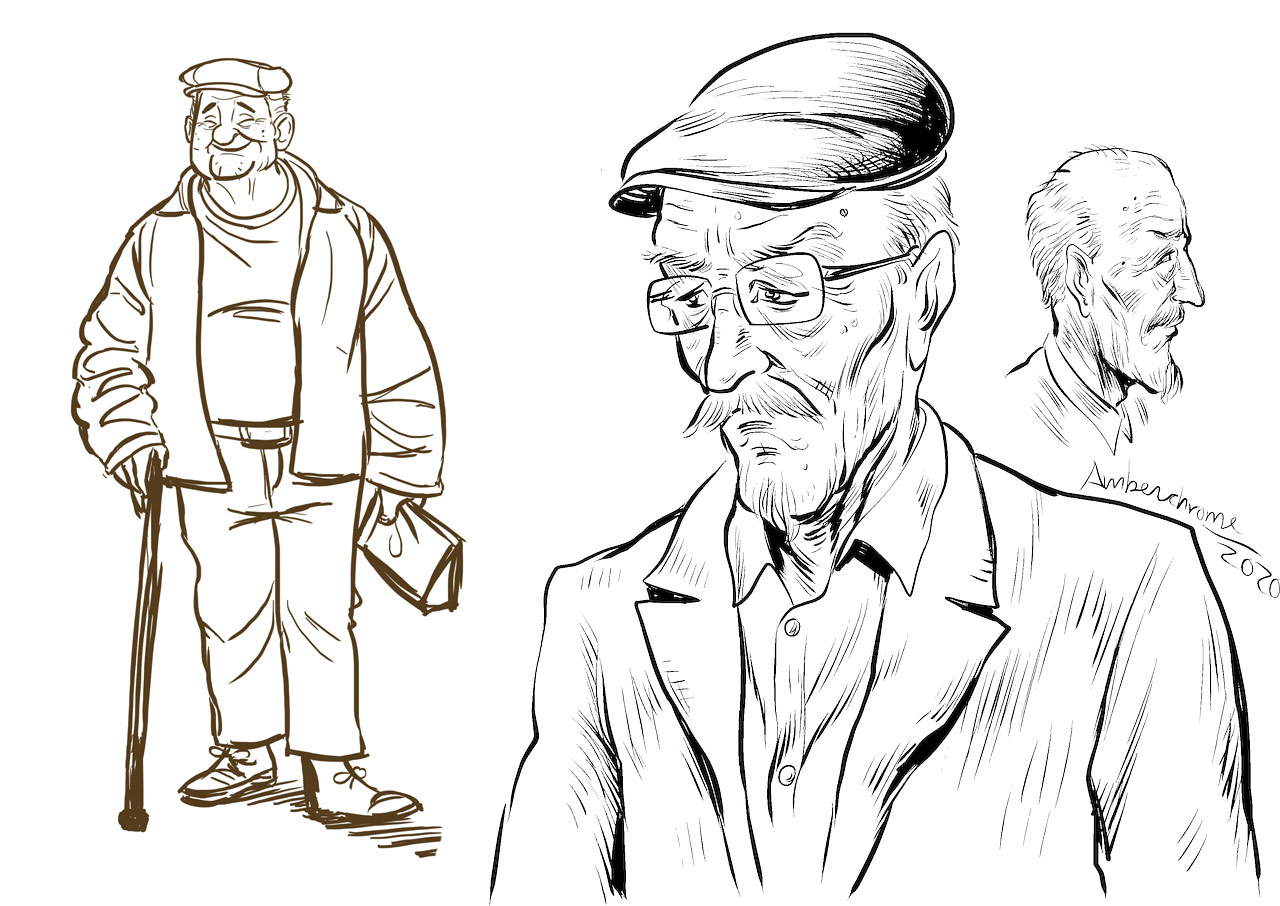

Age is a map. Honestly, when you sit down to start drawing an old man, you aren’t just sketching a person; you’re documenting decades of gravity, sunlight, and expression. Most beginners fail because they treat wrinkles like random scratches on a surface. That’s a mistake.

Wrinkles aren't just lines. They are structural folds. If you don’t understand the underlying bone loss and fat migration that happens as we age, your portrait will look like a young man wearing a rubber mask. It looks "off." You know the feeling. You spend three hours on a sketch, and it still feels like a caricature rather than a human being with a history.

The Bone Deep Reality of Aging Anatomy

Standard portrait tutorials usually focus on the "ideal" proportions—the Loomis method or the Riley rhythm lines. Those are great for a 25-year-old model. But for an older subject? The skull itself changes.

Research in the Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery has highlighted that facial aging isn't just about skin. It’s about "skeletal remodeling." Basically, the eye sockets (orbits) get wider and deeper. The jawbone—the mandible—actually loses volume.

When you start drawing an old man, you have to account for this recession. The chin might become less prominent, or the angle of the jaw might soften. Because the bone is receding, the skin has less "scaffolding" to hold onto. That’s why you get jowls. It’s physics. Gravity pulls the soft tissue down into those newly created gaps.

Look at the zygomatic bone—the cheekbone. In a young person, the fat pads sit high on that bone. In an older man, those fat pads slide down toward the mouth. This creates the nasolabial fold, that deep line running from the nose to the corner of the lips. If you just draw a line there, it’s a cartoon. To make it real, you have to shade the "shelf" of skin that is hanging over the crease.

🔗 Read more: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Why the Eyes are the Hardest Part

The eyes tell the story, but they are technically a nightmare to get right.

Ptosis is the medical term for drooping eyelids. It happens to almost everyone. The levator muscle, which lifts the eyelid, gets tired over seventy years. When you’re drawing an old man, the upper eyelid often disappears under a fold of skin from the brow.

Then there are the "bags" under the eyes. These aren't just dark circles. These are herniated fat pads. They have a specific weight. Notice how the skin there is almost translucent. You can often see tiny capillary networks or slight discolorations.

Don't forget the eyebrows. Men’s eyebrows often get bushier and more chaotic as they age. But the hair also thins in spots. Use quick, flicking strokes with a sharp H-grade pencil for the stray hairs, but keep the bulk of the brow soft. If you draw every hair with the same pressure, it looks like a hairpiece.

Lighting the Map: Form Over Line

Stop thinking in lines. Think in planes.

💡 You might also like: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

If you look at the work of Rembrandt, specifically his later self-portraits, he didn't obsess over every tiny crow’s foot. He obsessed over how light hit the different elevations of the face. An old man's face is a series of peaks and valleys.

If your light source is from the side—what we call Rembrandt lighting—one side of a wrinkle will be in bright highlight, and the other will be in deep shadow. There’s usually a mid-tone in between. That’s what gives the skin texture.

Texture and the "Paper Skin" Effect

Old skin is thinner. It's often called "parchment skin" because it loses its collagen and elastin. This means the skin doesn't bounce back.

When you’re drawing an old man, try using a blending stump sparingly. If you smudge everything, you lose that leathery, textured quality. Instead, use a technique called "scumbling" or small, circular marks to build up the uneven tone of the skin. Age spots—technically solar lentigines—aren't perfectly round. They’re irregular. They vary in opacity.

The Ears and Nose Never Stop Growing

Actually, that’s a bit of a myth. They don’t "grow" in the sense that they are producing new cells at a rapid rate. It’s more that the cartilage continues to break down and expand, and gravity pulls them downward.

📖 Related: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

An old man’s ears are often significantly larger in proportion to his head than a teenager’s. The lobes stretch. The nose becomes broader and the tip often droops. If you use the standard "eyes are in the middle of the head" rule without adjusting for the sagging features, the forehead will look way too big.

Hands: The Secondary Portrait

If you are drawing more than just the face, the hands are vital. The skin on the back of an old man's hand is incredibly thin. You should see the tendons. You should see the blueish bulge of the veins.

The knuckles often show signs of osteoarthritis—they get knobby and slightly deviated. Don't smooth them out. The character of an old man is found in these "imperfections."

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Symmetry: Nobody is perfectly symmetrical, especially not older people. One side of the face might have deeper laugh lines than the other. Maybe they’ve slept on their right side for fifty years. Capture that tilt.

- The "Cracked Earth" Look: Don't draw every wrinkle with the same intensity. If every line is dark, the face looks like a dry lakebed. Pick the "anchor" wrinkles—the ones that define the movement of the face—and let the others be suggestions.

- Ignoring the Neck: The "turkey neck" or the prominent cords of the neck muscles (platysmal bands) are huge age indicators. A sharp jawline on an 80-year-old looks fake. Blend the jaw into the neck with soft shadows.

Practical Next Steps for Your Portrait

Start by doing a "skull study." Before you even try drawing an old man from a photo, look at a diagram of a human skull and then look at a photo of an elderly person. Try to visualize where the bone has shrunk.

Next, grab a 2B pencil and focus entirely on the "T-zone"—the brow, the nose, and the folds around the mouth. Don't worry about the hair or the ears yet. Just try to capture the weight of the cheeks.

Use a kneaded eraser to "lift" highlights off the tops of wrinkles. This is the secret to making them look three-dimensional. A line is a 2D concept; a fold is 3D. The eraser creates the light that makes the fold pop.

Finally, find a high-resolution reference photo that hasn't been filtered. Avoid celebrity photos that have been retouched. You want to see the pores, the broken capillaries, and the uneven pigment. That is where the beauty of the drawing lives. Authenticity beats "prettiness" every single time in portraiture.