You probably grew up with the Grinch, a Lorax, and a Cat in a striped hat. Most people did. But if you look at the portfolio of Theodor Seuss Geisel between 1941 and 1943, you won't find many whimsical creatures or rhyming nonsense. Instead, you'll find Hitler, Mussolini, and some of the most biting, controversial political commentary of the 20th century.

Dr Seuss WW2 cartoons are a shock to the system.

It's jarring. Imagine the person who wrote Green Eggs and Ham drawing a "Slap the Jap" poster or depicting Charles Lindbergh as an ostrich sticking its head in the sand while Europe burns. This wasn't a side project. For two years, Geisel was the chief editorial cartoonist for the New York City newspaper PM. He produced over 400 cartoons during that stretch. He was loud. He was angry. Honestly, he was often quite problematic by modern standards. But to understand the man, you have to look at the ink he spilled before he ever became a household name for children’s literacy.

Why Geisel Swapped Whimsy for Warfare

Theodor Geisel didn't just stumble into political cartooning. He was deeply frustrated. By 1940, the United States was locked in a fierce debate over isolationism. On one side, you had the "America First" movement, led by figures like Charles Lindbergh. On the other, you had people like Geisel who believed that ignoring the rise of Fascism in Europe was moral suicide.

He couldn't sit still.

Geisel joined PM because it was a platform that accepted no advertising and took a hard-left, interventionist stance. He hated the idea that Americans could just "stay out of it." In one of his most famous Dr Seuss WW2 cartoons, he drew a woman wearing an "America First" sweater reading a book called The Wolf Chewed Up the Children and Spit Out Their Bones to two horrified kids. The caption? "Adolf the Wolf." The message? Isolationism is just a bedtime story we tell ourselves to ignore a slaughter.

He was ruthless. He didn't just poke fun at the Axis powers; he went after domestic figures he viewed as cowards or traitors. He drew US Senators as ostriches. He drew the Nazi regime as a massive, grinding machine fueled by human lives. It was a far cry from "One Fish, Two Fish."

📖 Related: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

The Darkness in the Ink: Racism and Propaganda

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. Or rather, the way Geisel drew Japanese people.

If you look through the archives of Dr Seuss WW2 cartoons, you’re going to see some deeply offensive imagery. Geisel utilized the common racial caricatures of the era—buck teeth, slanted eyes, Coke-bottle glasses. It wasn't just "of its time." It was active wartime propaganda designed to dehumanize the enemy.

One specific cartoon from February 13, 1942, remains a massive stain on his legacy. It depicts a long line of Japanese-Americans waiting to pick up packages of TNT from a "Honorable 5th Column" station, implying they were all sleeper agents waiting for a signal from Tokyo. This was published right as the US government was moving toward Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced internment of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans.

Geisel wasn't just a bystander. He helped fuel the fire.

Years later, he tried to make amends. He wrote Horton Hears a Who! after visiting Japan in 1953, and many scholars, including Richard H. Minear (author of Dr. Seuss Goes to War), view the book’s central theme—"A person's a person, no matter how small"—as a direct apology for his wartime xenophobia. He even dedicated the book to a Japanese friend. But the cartoons remain. They are a permanent record of how even a "gentle" genius can be swept up in the vitriol of total war.

Turning the Tide: From PM to the Army

By 1943, Geisel felt that drawing cartoons wasn't enough. He wanted to get closer to the action. He joined the United States Army as a Captain and became the commander of the Animation Department of the First Motion Picture Unit.

👉 See also: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

This is where things get interesting for film nerds.

He worked alongside legendary director Frank Capra. Together, they created the Private Snafu series. These were instructional, adult-oriented cartoons designed to teach soldiers what not to do. Snafu—an acronym for "Situation Normal: All Fouled Up"—was a bumbling soldier who constantly messed up security protocols or hygiene.

The humor was bawdy. It was crude. It was definitely not for kids. But the DNA of Dr Seuss was all over it. You can see the proto-Grinch in some of the character designs. You can hear the rhythmic cadence in the dialogue.

He also co-wrote Your Job in Germany and Our Job in Japan, orientation films for occupying forces. Your Job in Germany was later adapted into the Academy Award-winning documentary Design for Death. Think about that: the man who wrote The Lorax won an Oscar for a film about the rise of Japanese militarism.

The Connection to the Classics

You might think the Dr Seuss WW2 cartoons were just a weird detour. They weren't. They were the laboratory where he refined his most famous themes.

- The Sneetches: This story about birds who think they are better than others because of stars on their bellies? That's a direct response to his reflections on the Holocaust and Nuremberg laws.

- Yertle the Turtle: Geisel explicitly stated that Yertle was a representation of Adolf Hitler. The turtle king who builds a throne by stacking his subjects until the one at the bottom burps and topples the whole empire? That’s his commentary on the fragility of totalitarianism.

- Horton Hears a Who: As mentioned, this was his pivot toward universal human rights.

He learned how to use "the big lie" and "the big truth." He realized that if you can use a cartoon to make people hate, you can also use a cartoon to make people think. He took the visual language of propaganda—bold lines, exaggerated features, clear moral stakes—and applied it to children’s literature to teach empathy instead of enmity.

✨ Don't miss: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The Archive Today: Where to See Them

If you want to see these for yourself, the Mandeville Special Collections Library at the University of California, San Diego, holds the bulk of his original work. It’s a massive archive.

You’ll notice the ink is often heavy. He used a lot of cross-hatching. There’s a frantic energy to the drawings that feels different from his later, more polished books. It’s the work of a man who thought the world was ending and was trying to draw a way out of the darkness.

It’s worth noting that while some of these cartoons are celebrated for their anti-fascist stance, many are omitted from modern retrospectives. Collectors and historians often grapple with how to present this work. Do you highlight the bravery of an artist standing up to the Nazis when no one else would? Or do you condemn the racism he promoted against Japanese-Americans?

The answer is probably both.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Seuss Archives

Looking back at Dr Seuss WW2 cartoons isn't just a history lesson. It offers a blueprint for how we consume and create media today.

- Contextualize Everything: When you see a Seuss book today, remember it wasn't written in a vacuum. His books are responses to the world he saw. Read them with that "political eye" and you'll find layers you missed as a kid.

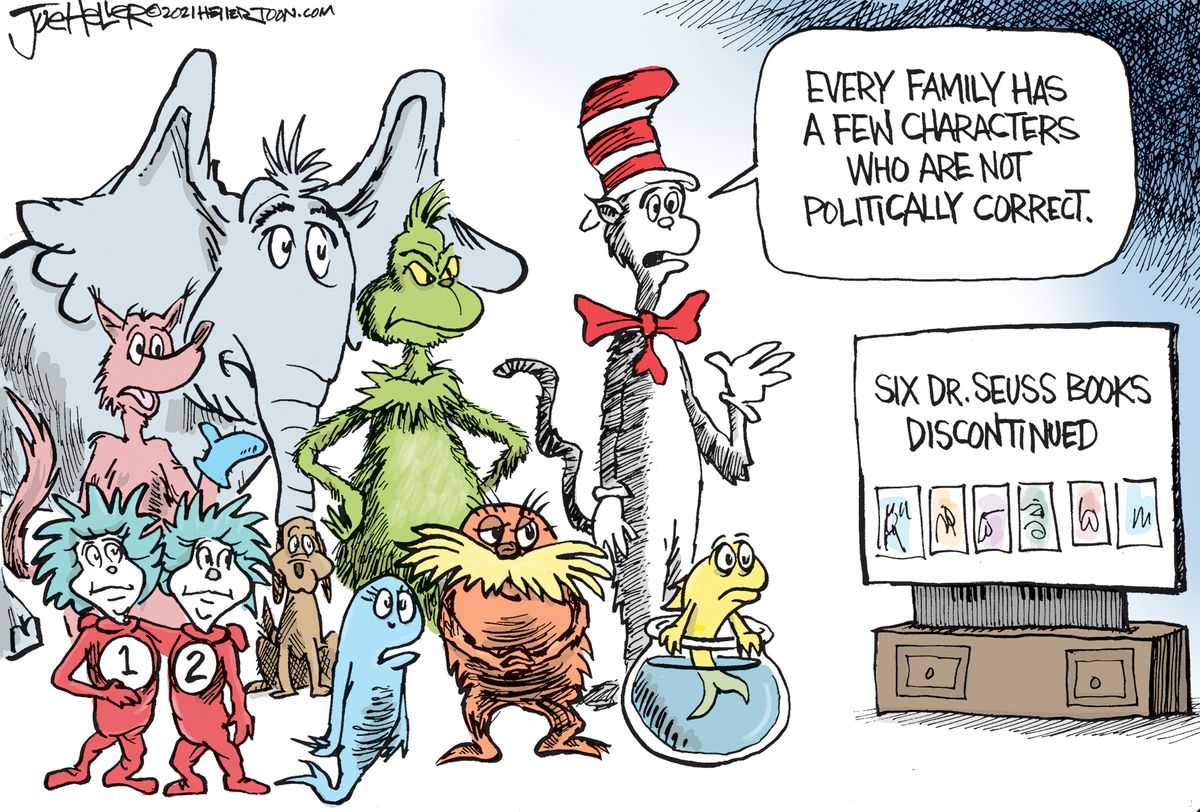

- Acknowledge Complexity: It is possible for an artist to be both a hero and a villain in the same story. Geisel’s work against the Nazis was vital; his work against Japanese-Americans was harmful. We don't have to "cancel" or "sanitize" him to recognize both truths.

- The Power of Satire: Geisel proved that simple drawings could communicate complex geopolitical realities better than a thousand-word editorial. If you're a creator, never underestimate the power of a single, well-placed metaphor.

- Growth is Possible: The transition from the man who drew "The 5th Column" to the man who wrote Horton Hears a Who is one of the most significant moral arcs in American art. It shows that people—and their work—can evolve if they are willing to confront their own biases.

To truly understand Dr Seuss, you have to look at the shadows. You have to look at the propaganda. Only then does the light in his children’s books actually make sense. He knew what a world without empathy looked like because he had spent years drawing it.

If you want to dive deeper, check out Dr. Seuss Goes to War by Richard H. Minear. It's the definitive collection and provides the necessary historical framework to understand why these cartoons look the way they do. Also, look for the Private Snafu shorts on public domain archives; they are a fascinating look at the bridge between his political work and his eventual career as the world's most famous children's author.