You’re standing on a sidewalk in Boston or maybe a slushy corner in Philly, staring at your phone. The radar map shows a giant blob of dark green right over your head, but when you look up, the sky is just a depressing shade of gray and your jacket is bone dry. It’s frustrating. We have some of the most advanced meteorological tech on the planet scattered across the I-95 corridor, yet "doppler radar for the northeast" still feels like a coin flip during a Nor'easter. Why?

The truth is that radar isn't a camera. It doesn't "see" the rain; it hears the echo of energy bouncing off stuff in the air. In the Northeast, where the weather changes faster than a New York minute, that distinction is everything.

The Magic and the Mess of the NEXRAD Network

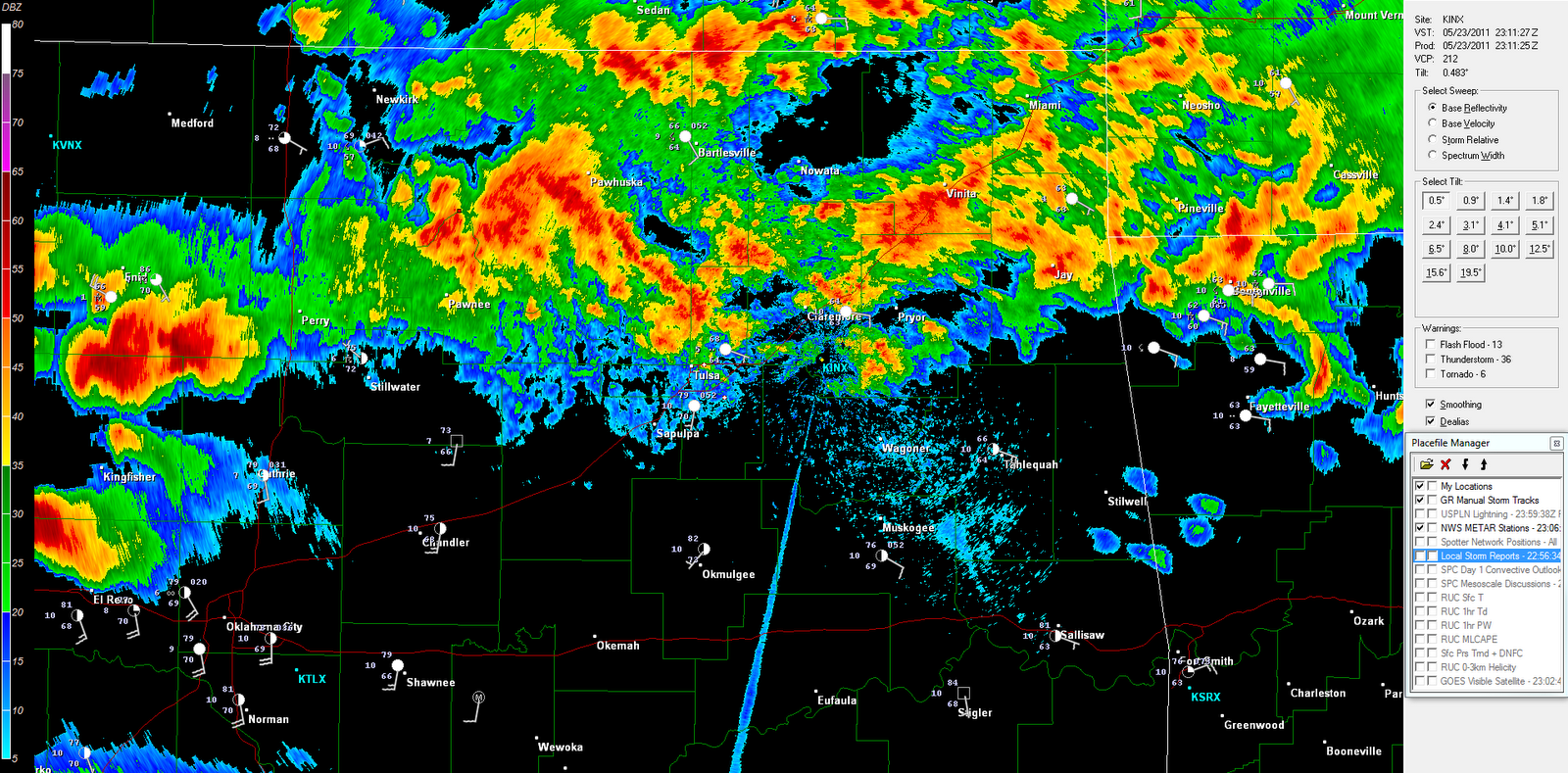

Basically, we rely on the WSR-88D, which is the technical name for those giant white soccer balls you see sitting on towers. There are key stations in Gray (Maine), Taunton (Massachusetts), Upton (New York), and Mount Holly (New Jersey). These things are beasts. They pulse out microwave energy, wait for it to hit a snowflake or a raindrop, and then listen for the return.

But here is the kicker. The Earth is curved.

Because the beam travels in a straight line, the further you get from the physical tower, the higher in the atmosphere the beam is scanning. If you’re in a "radar hole"—like parts of the Hudson Valley or the hilly terrain of Western Mass—the radar might be screaming that there’s a blizzard 5,000 feet up, while at the surface, the air is too dry for anything to actually land. Meteorologists call this virga. It’s the ultimate tease.

🔗 Read more: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

Why the "Doppler" Part Actually Matters

The term Doppler refers to the frequency shift. You know that sound a siren makes when it gets higher as it approaches and lower as it moves away? Christian Doppler figured that out in the 1840s. In the context of the Northeast, this allows the National Weather Service (NWS) to see the wind inside the storm.

During a 2020 tornado outbreak in Connecticut, it wasn't the "reflectivity" (the colors you see on the news) that saved lives; it was the "velocity" data. By comparing the wind moving toward the radar and the wind moving away, computers can spot a couplet—a tiny spinning vortex—long before a funnel cloud actually touches a backyard in Cheshire.

Dual-Pol: The Secret Weapon for New England Winters

A decade ago, radar only sent out horizontal pulses. It was great at measuring how wide a drop was, but not much else. Then came Dual-Polarization (Dual-Pol). Now, the radar sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses.

This is huge for us. Why? Because a raindrop is flat like a hamburger bun, and a snowflake is all over the place.

💡 You might also like: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

- Correlation Coefficient (CC): This tells the NWS if everything in the air is the same shape. If the CC drops, it means the radar is seeing a mix of rain, snow, and sleet.

- Differential Reflectivity (ZDR): This helps distinguish between a giant, wet snowflake and a small, dense hailstone.

Honestly, without Dual-Pol, forecasting the "rain-snow line" during a January storm would be pure guesswork. In the Northeast, three miles can be the difference between six inches of powder and a flooded basement. The radar helps us see exactly where that melting layer—the "bright band"—is sitting in the sky.

The Geography Problem: Mountains and Oceans

The Northeast is a nightmare for radar beam propagation. You’ve got the Appalachian spine to the west and the Atlantic to the east.

When a storm moves up the coast, the radar at Upton (KOKX) is looking out over the water. But salt spray can actually mess with the signal. Then you have "anomalous propagation." This happens when a temperature inversion—common in New England springs—bends the radar beam back down toward the ground. Suddenly, the radar screen shows a massive storm over Hartford, but it’s actually just the beam hitting the ground because the atmosphere is acting like a funhouse mirror.

How to Read Doppler Like a Pro

Stop looking at the "composite" view on your weather app. Most free apps default to composite, which shows the strongest reflection from any altitude. It’s misleading.

📖 Related: The Dogger Bank Wind Farm Is Huge—Here Is What You Actually Need To Know

You want "Base Reflectivity." This shows you what’s happening at the lowest tilt, closest to the ground. If you see a weird jagged line moving toward the coast, that’s often a sea-breeze front or a "gust front" from a thunderstorm.

Also, watch for "bins." Radar data is chopped into little blocks. In the Northeast, high-resolution (Super-Res) data is now standard, allowing us to see features as small as 250 meters. This is how we spot "debris balls" in the rare event of a tornado—it’s literally the radar bouncing off pieces of houses or trees lofted into the air.

The Future: Phased Array and Beyond

The current WSR-88D units are aging. They are mechanical; the dish has to physically rotate and tilt. It takes about 4 to 6 minutes to complete a full scan of the sky. In a fast-moving squall line on the Long Island Sound, 5 minutes is an eternity.

The next leap is Phased Array Radar (PAR). Instead of a spinning dish, it uses a flat panel with thousands of tiny antennas that steer the beam electronically. It can scan the entire sky in under a minute. While the Northeast doesn't have a full network of these yet, the research being done at the National Severe Storms Laboratory suggests this will eventually make our current doppler radar for the northeast look like a black-and-white TV.

Practical Steps for Tracking Northeast Weather

Don't just rely on the colorful blobs. To really understand what's coming, follow these steps:

- Check the CC (Correlation Coefficient) Map: During a winter storm, look for a "blue" or "yellow" drop in the middle of the red. That's your rain-snow transition line. If that line is moving toward you, get the shovel ready.

- Use the "Terminal Doppler": Major airports like Logan, JFK, and Newark have their own specialized radars (TDWR). They have a shorter range but much higher resolution for low-level wind shear. If you live near a major city, these radars often give a better "street-level" view than the big NWS stations.

- Identify Radar Holes: Know your distance from the nearest station. If you are more than 60 miles from Taunton or Mount Holly, remember the radar is looking several thousand feet above your head. What you see on the screen might take 20 minutes to actually hit the ground.

- Verify with mPING: Use the mPING app from NOAA. It lets citizens report what is actually falling (rain, ice, snow) at their specific location. Meteorologists use this to "ground truth" what the doppler radar is telling them.

Radar is a tool, not a crystal ball. Understanding that it’s measuring echoes—not just "weather"—is the first step to never being surprised by a "sudden" downpour again.