Nicolas Roeg didn’t just make a horror movie. He made a puzzle about how we process grief, and honestly, we’re still trying to put the pieces together fifty years later. When people talk about Don't Look Now 1973, they usually jump straight to the "red coat" or that infamous, controversial bedroom scene between Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland. But there is so much more happening under the surface of Venice’s murky canals.

It’s a film that demands you pay attention. It punishes you if you don't.

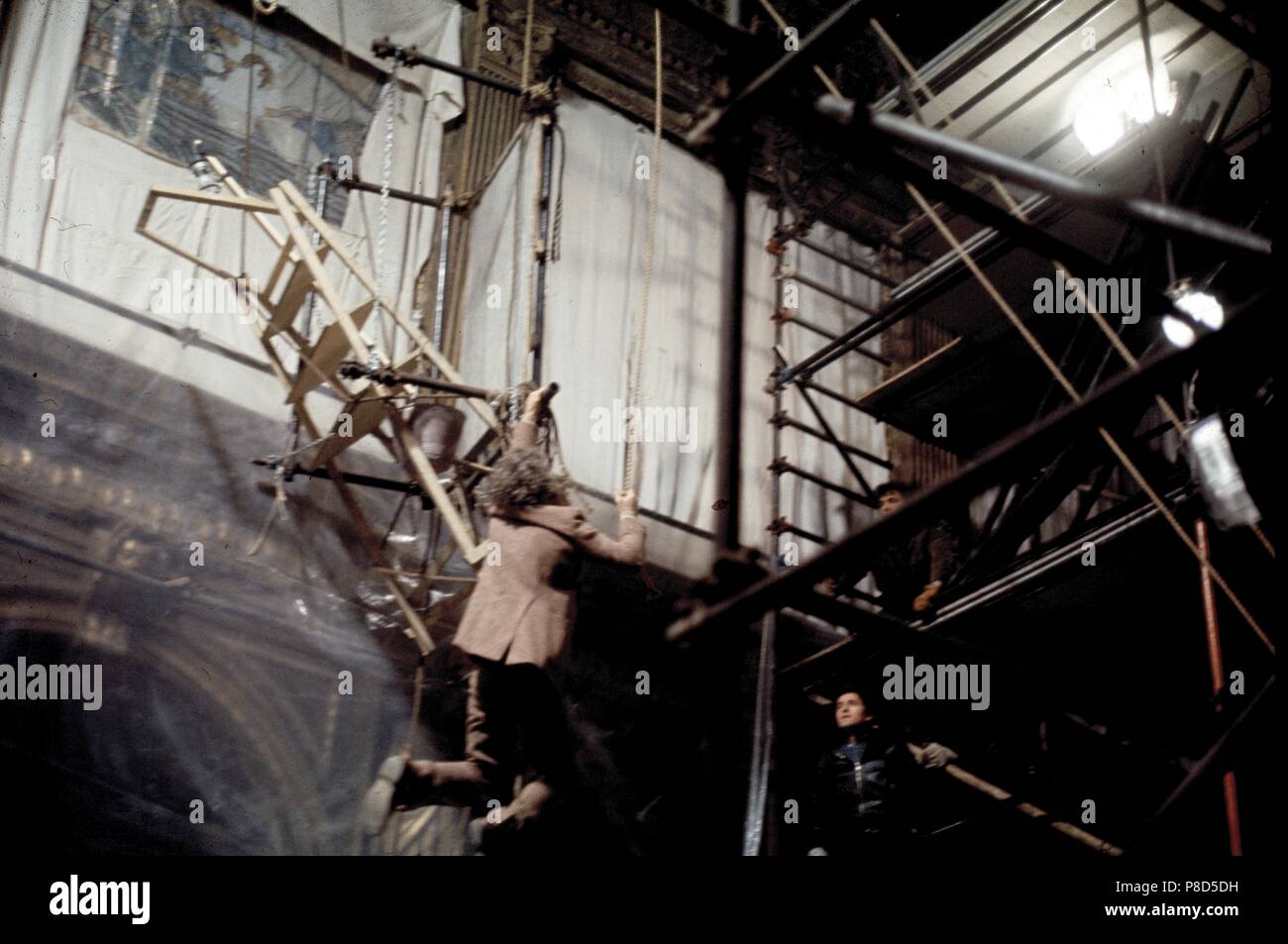

Based on a short story by Daphne du Maurier, the film follows John and Laura Baxter as they retreat to a decaying, wintry Venice following the accidental drowning of their daughter. John is there to restore an old church. Laura is just trying to survive the day. But when they encounter two sisters—one of whom claims to be psychic and sees their deceased daughter sitting between them—the movie shifts from a standard drama into a terrifying exploration of second sight and premonition.

The Visual Language of Grief and Water

Most directors use dialogue to tell you how a character feels. Roeg uses editing. He cuts between the past, the present, and the future so rapidly that you start to feel as disoriented as the characters. It’s called "fractured" editing.

Water is everywhere. It’s the thing that took their daughter, and it’s the thing that surrounds them in Venice. But in Venice, the water isn't life-giving; it’s stagnant, smelly, and full of secrets. You've probably noticed how the color red pops against the grey, stone backdrop of the city. That isn't an accident. Every time you see a flash of red—a scarf, a poster, a piece of glass—it’s a breadcrumb leading John (and us) toward the inevitable.

John Baxter is a man of logic. He’s an architect. He believes in things he can touch and fix. This is his fatal flaw. He refuses to believe in the "unseen," even when his own subconscious is screaming at him through visions he can't explain. He thinks he’s chasing his daughter’s ghost to save her, or perhaps to save himself, but he’s actually walking toward his own execution.

👉 See also: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Why the Venice Setting Changes Everything

Venice in the winter is miserable. It's not the postcard version you see in travel brochures. It’s wet, cold, and claustrophobic. Roeg used this to emphasize the isolation of the Baxters. They are surrounded by people, yet they are utterly alone in their mourning.

The city acts as a labyrinth. The narrow alleys and dead ends reflect John’s mental state. He thinks he knows the way, but he’s constantly getting lost. If you've ever walked through Venice at night, you know that feeling of being watched by the buildings themselves. Roeg captures that paranoia perfectly. He didn't want a "pretty" movie; he wanted a movie that felt like a damp basement.

That Ending: Breaking Down the Red Macabre

We have to talk about the ending of Don't Look Now 1973. If you haven't seen it, stop reading. Seriously.

The reveal of the "figure in red" is one of the most jarring moments in cinema history. For the entire film, John believes he sees his daughter in her red mackintosh running through the Venetian streets. He follows her. He thinks it’s a miracle or a haunting. When he finally corners the figure, it’s not his daughter. It’s a female dwarf with a meat cleaver—a serial killer who has been stalking the city.

It’s a "gotcha" moment that works because it’s deeply rooted in the film’s themes. John’s "second sight" was real, but his interpretation was wrong. He saw his own funeral earlier in the film and didn't realize it. He saw the red coat and projected his grief onto it.

✨ Don't miss: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The violence is quick. It's brutal. It's messy.

Critics at the time were polarized. Some thought the ending was a cheap thrill, while others, like the legendary Pauline Kael, recognized it as a profound statement on the limits of human perception. It’s a reminder that we often see what we want to see rather than what is actually in front of us.

The Controversy of the Sex Scene

You can't discuss this film without mentioning the hotel room scene. At the time, it was so realistic that rumors circulated for decades that Sutherland and Christie weren't acting. They’ve both denied it repeatedly, but the rumor persisted because the chemistry was so raw.

Roeg’s genius here was the intercutting. He spliced scenes of the couple getting dressed for dinner with the act of lovemaking itself. It removed the "prurient" nature of the scene and turned it into a study of intimacy. It showed a husband and wife reconnecting through their shared tragedy. It made them human. When John dies at the end, the loss hurts more because we’ve seen that moment of genuine connection.

Technical Mastery and Roeg’s Legacy

The cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond is masterclass level stuff. He uses long lenses to compress the space, making the city feel like it’s closing in on the Baxters. The lighting is naturalistic, almost documentary-like, which makes the supernatural elements feel even more grounded and terrifying.

🔗 Read more: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

- Color Theory: Red is the warning. It represents the blood of the past and the blood of the future.

- Sound Design: The sound of splashing water is often heightened to an uncomfortable level.

- Structure: The film doesn't follow a linear path; it follows an emotional one.

Many modern horror directors, including Ari Aster (Hereditary) and Jordan Peele, have cited Roeg’s work as a massive influence. You can see the DNA of Don't Look Now 1973 in any film that uses "elevated" horror to discuss trauma. It proved that a "scary" movie could also be a deeply intellectual one.

How to Watch It Today

If you’re planning to revisit this classic or watch it for the first time, don't just put it on in the background while you scroll on your phone. It’s a movie that requires total immersion.

Look for the 4K restoration by Criterion or StudioCanal. The grain and the colors are vital to the experience. Pay attention to the background characters. Notice how many times John almost sees the truth before it hits him.

Actionable Takeaways for Cinephiles

- Watch for the motifs: Track every time the color red appears. You’ll notice it’s almost always linked to a moment of danger or a realization John ignores.

- Compare to the source material: Read Daphne du Maurier’s short story. It’s much shorter and leaner, but seeing how Roeg expanded the visual language of the story is a lesson in adaptation.

- Analyze the "Second Sight": Research the concept of "pre-cognition" in the context of the 1970s. The film was made during a period of high public interest in the paranormal (think The Exorcist or The Omen), but it handles the subject with much more ambiguity.

The film is a reminder that grief doesn't just go away. It changes how we see the world. It blurs the lines between what is real and what we fear. That is why Don't Look Now 1973 remains a staple of British cinema and a terrifying mirror for our own anxieties.

Don't look away. You might miss the very thing that’s coming for you.