You probably think of it as just another standard on the holiday playlist. It’s the one with the "tail as big as a kite" and the "silver and gold" imagery that feels right at home next to Silent Night or Joy to the World. But Do You Hear What I Hear wasn't born from a place of cozy fireplaces or snowy New England streets. It was written in a state of absolute, bone-chilling terror.

October 1962.

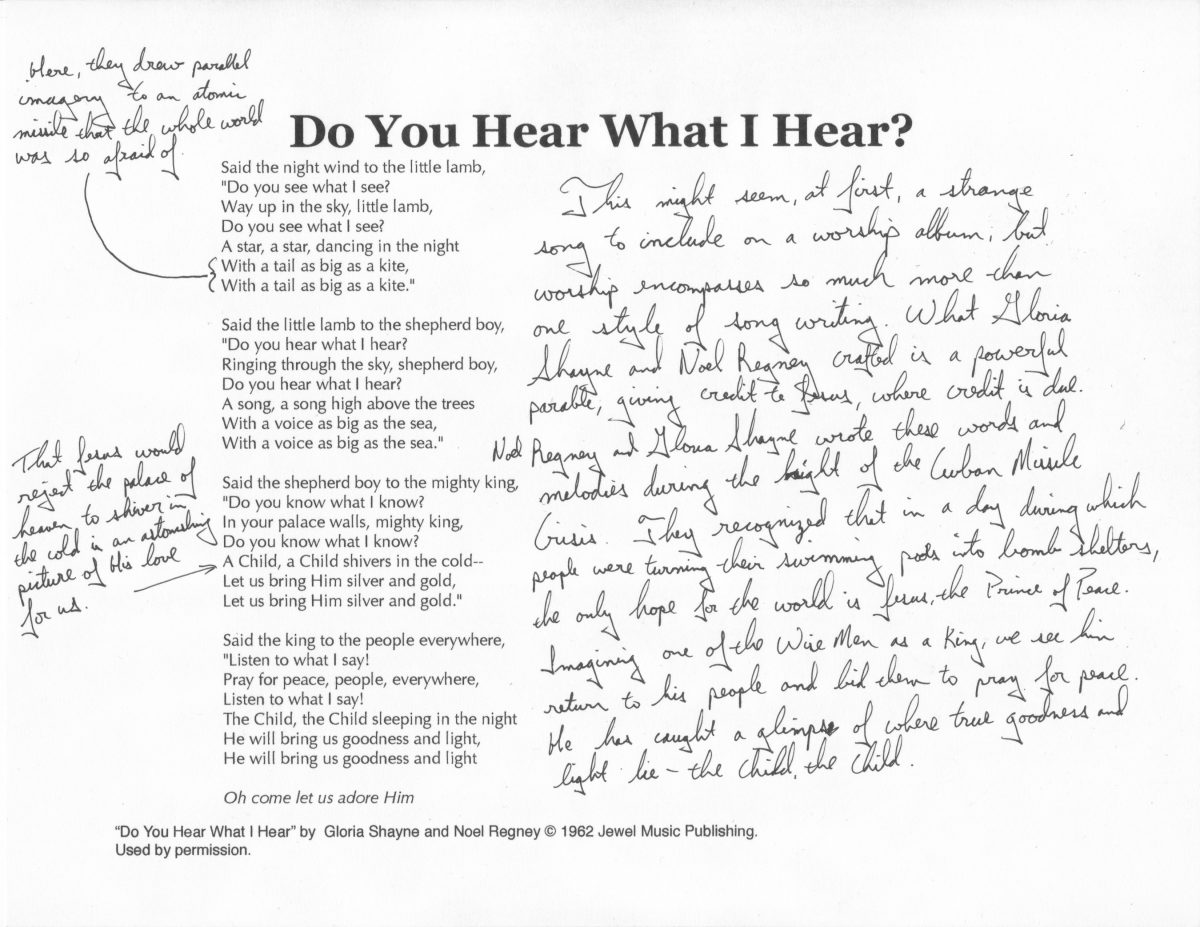

The Cuban Missile Crisis was at its peak. Americans were glued to their grainy television sets, watching news reports about Soviet ships and nuclear warheads just 90 miles off the coast of Florida. People were genuinely convinced the world was ending. It’s hard to wrap our heads around that level of collective anxiety today, but for Noel Regney and Gloria Shayne, it was the air they breathed.

They were a married songwriting duo living in Manhattan. Noel, a Frenchman who had been drafted into the Nazi army against his will before deserting to join the French Resistance, knew what war looked like. He’d seen the worst of humanity. When he walked down a New York City street during that tense October, he saw two mothers pushing baby strollers. The mothers looked at each other with eyes full of dread, but the babies—they were just smiling.

That specific moment of innocence in the face of annihilation sparked the first line of Do You Hear What I Hear.

The Song That Was Actually a Prayer for Peace

Most people assume the song is a literal retelling of the Nativity story. It isn't. Not exactly. While it uses the framework of the birth of Jesus, Regney and Shayne wrote it as a plea for nuclear disarmament.

When the lyrics mention a "star, dancing in the night," they weren't just thinking about the Star of Bethlehem. In the context of 1962, a bright light in the sky often meant something much more sinister: a missile. By framing the song as a call to "pray for peace everywhere," the couple was speaking directly to the geopolitical nightmare unfolding at that very second.

Noel wrote the lyrics. Gloria, who was a professional pianist and composer, wrote the music. Usually, it was the other way around for them. But Noel had the words burning in him. He famously said he couldn't even sing the song through without breaking down in tears because the emotions were so raw.

They took it to the Harry Simeone Chorale. You might know them from their definitive version of The Little Drummer Boy. They recorded it, and it was released just after the crisis peaked. It sold a quarter of a million copies in the first week. People weren't just buying a Christmas song; they were buying a sense of relief.

🔗 Read more: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

Why the Lyrics Feel a Little... Off

Have you ever noticed the imagery is a bit strange?

"A tail as big as a kite."

That’s not how we usually describe the Star of Bethlehem in traditional carols. It’s a very specific, visual description. It sounds like something a child would say, which was intentional. Regney wanted to capture the perspective of the marginalized—the night wind, the lamb, the shepherd boy—all moving up the social ladder to eventually reach the King.

The "King" in the song isn't just a biblical figure, either. In the final verse, the King speaks to "people everywhere." He tells them to listen to what he says. It’s a command for global unity.

"Pray for peace, people everywhere."

It is a blatant, unapologetic anti-war anthem disguised as a lullaby.

Bing Crosby and the Commercial Pivot

If the Harry Simeone Chorale made it a hit, Bing Crosby made it an institution.

In 1963, a year after the original release and just weeks before the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Crosby recorded his version. Bing was the undisputed king of Christmas. If he sang it, it was official. His deep, velvet baritone smoothed over some of the jagged edges of the song's origin. He turned the "prayer for peace" into a "holiday classic."

💡 You might also like: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Since then, it has been covered by everyone. Whitney Houston gave it a soulful, powerhouse gospel vibe. Carrie Underwood brought the country-pop shine. Spirited versions by Pentatonix and Kelly Clarkson keep it on the charts every December.

But honestly? Most of these covers miss the point. They play it as a triumphant, upbeat celebration. If you go back and listen to the original 1962 recording, there is a haunting, marching quality to it. It sounds like a procession. It sounds urgent.

The Compositional Magic of Gloria Shayne

We need to talk about Gloria Shayne. Often overshadowed by the "lyricist with a war past" narrative of her husband, she was a powerhouse. She wrote "Goodbye Cruel World" for James Darren and "Almost There" for Andy Williams.

The melody she crafted for Do You Hear What I Hear is a masterclass in tension and release. The way the song builds—starting with the whisper of the wind and ending with the booming declaration of the King—mirrors the way a rumor or a message spreads. It starts small and becomes undeniable.

She used a simple, rhythmic pulse that feels like a heartbeat. It’s steady. It’s reassuring. In a world that felt like it was spinning out of control in 1962, that steady beat was exactly what the public’s nervous system needed.

Common Misconceptions About the Song

It’s an ancient traditional carol.

Nope. It’s younger than the Ford Mustang. It was written in 1962. It just feels old because it uses archaic-sounding language like "Shepherd boy" and "mighty king."It’s strictly about the Bible.

As established, it's a political protest song. Regney was a pacifist. He wanted to use the most universal story of peace he knew—the birth of a child—to tell the leaders of the Cold War to stop the madness.Noel Regney was a Nazi.

This is a gross oversimplification that pops up in trivia circles. Regney was a Frenchman. He was forcibly conscripted into the German army because he lived in an occupied zone. He spent his time there actively sabotaging them and eventually escaped to join the French Underground. He hated war because he was a victim of it.📖 Related: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

How to Listen to It Now

Next time this song comes on while you're standing in line at the grocery store or driving through holiday traffic, try to strip away the tinsel.

Listen to the words as if you're hearing them for the first time in a world that might not exist tomorrow.

- The Night Wind: Think of it as the ignored messenger.

- The Lamb: The innocent bystander.

- The Shepherd Boy: The youth who has to carry the message to power.

- The King: The leader who actually listens.

It’s a blueprint for communication and empathy. It’s about passing a message of hope from the lowest rungs of society to the highest.

Making the Song Part of Your Season

If you're a musician or just someone who puts together the annual family playlist, try to find the versions that honor the original intent. The 1962 Harry Simeone Chorale version is the gold standard for a reason. It has a gravity that the modern, over-produced versions lack.

Actionable Insights for the Curious:

- Compare the Versions: Put the Bing Crosby version side-by-side with the Whitney Houston version. Notice how the "Peace" message is emphasized differently in 1963 versus 1987.

- Read the Lyrics as Poetry: Forget the melody for a second. Read the text. It functions perfectly as a poem about the transmission of truth.

- Contextualize Your History: If you have kids or students, use the song as a gateway to talk about the Cold War. It's a perfect example of how art reacts to the political climate of its time.

The world is still a loud, chaotic place. We still have "people everywhere" praying for peace. That’s probably why Do You Hear What I Hear hasn't faded away like so many other topical songs from the sixties. It tapped into a universal human fear, and more importantly, a universal human hope. It reminds us that even when the sky feels like it's falling, there's a reason to keep singing.

Stay curious about the stories behind the songs. Usually, the "classic" everyone knows has a much darker, much more interesting beginning than the radio edit lets on.