People often talk about measles like it’s a relic of the past, something your grandma caught back in the fifties and stayed home from school for a week. You might hear it described as a "rite of passage" or just a nasty rash followed by a few days of fever. But when you look at the hard data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC, a much darker picture emerges. Do people die from measles? Yes. They do. In fact, they die in numbers that are honestly staggering for a disease that we have a highly effective vaccine for.

It isn't just a fever. It’s a systemic assault.

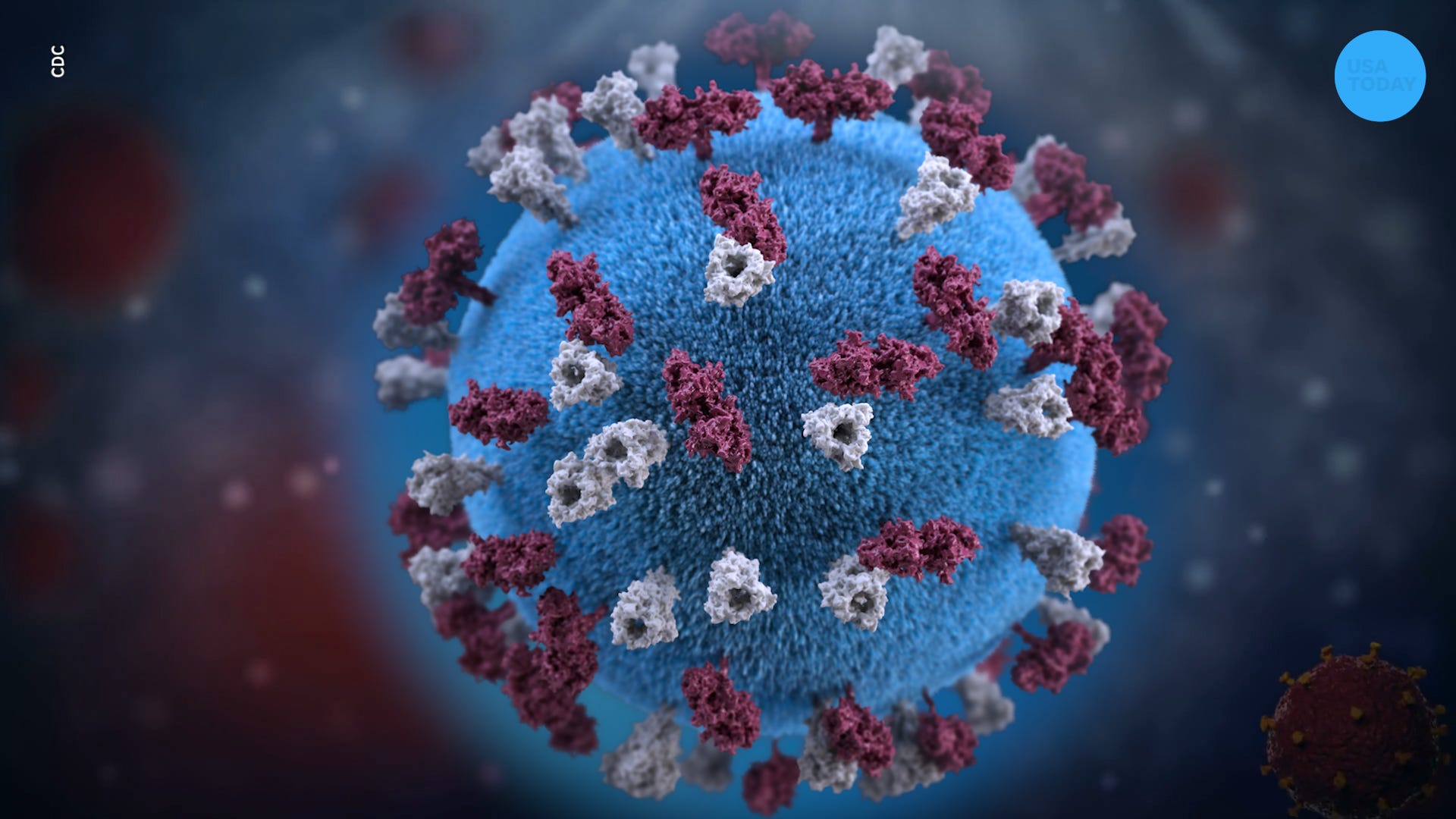

The virus doesn't just hang out on the skin. It goes deep. It attacks the lungs, the brain, and the very foundation of the immune system. While the majority of people in high-income countries might recover without permanent damage, the global reality is different. In 2023 alone, there were an estimated 10.3 million cases worldwide, and the death toll rose to over 107,000 people. Most of them were kids under the age of five. That is a lot of families grieving over a preventable tragedy.

Why measles is more than just a rash

When we ask if people die from this, we have to look at how it happens. Measles is a respiratory virus, but it’s famously nicknamed "the great disguiser" because it clears the way for other killers.

The virus causes what scientists call "immune amnesia." Basically, it wipes out the memory cells of your immune system. If you’ve already had the flu, or pneumonia, or a dozen other bugs, your body usually remembers how to fight them. Measles hits the reset button. For months or even years after "recovering" from the rash, a person is significantly more vulnerable to other infections. Many people don't die from the measles virus itself; they die from the secondary bacterial pneumonia that moves in while the immune system is distracted and broken.

Pneumonia is the most common cause of death in children who contract measles. The lungs get inflamed, they fill with fluid, and the body just can't get enough oxygen. It’s a terrifying way to go.

📖 Related: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

The brain and the long-term threat

Then there’s the brain. This is where things get really heavy. Encephalitis—swelling of the brain—occurs in about 1 out of every 1,000 cases. Some people recover. Others are left with permanent deafness or intellectual disabilities.

But there is a "ghost" version of the disease called Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE). It is rare, but it is 100% fatal. SSPE is a slow-motion tragedy. A child catches measles, seems to get better, and then, 7 to 10 years later, the virus—which has been dormant in the brain—reawakens. It begins a slow, progressive destruction of the central nervous system. It starts with mild behavioral changes and ends with the loss of the ability to walk, talk, or swallow. There is no cure. When we discuss the mortality of measles, SSPE is the ultimate reminder that this virus doesn't always leave when the rash fades.

Breaking down the risk factors

Who is most at risk? It isn't random.

- Malnourished children: Specifically those lacking Vitamin A. In these cases, the mortality rate can soar to 10% or higher.

- The immunocompromised: People with HIV, leukemia, or those on chemotherapy can’t fight the virus off.

- Infants: Those too young to be vaccinated (usually under 12 months) rely entirely on "herd immunity" to stay safe.

- Unvaccinated adults: Interestingly, adults who catch it often have a much harder time than school-aged kids, frequently ending up hospitalized with severe respiratory distress.

Do people die from measles in developed nations?

It’s easy to look at global stats and think, "That’s a problem for other places." But that’s a dangerous mindset. In the United States and Europe, the death rate is roughly 1 to 3 deaths for every 1,000 reported cases. That sounds low until you realize how fast measles spreads.

It is one of the most contagious diseases known to man. If one person has it, 90% of the people around them who aren't immune will catch it. You don't even have to touch the person. The virus hangs in the air for up to two hours after an infected person has left the room.

👉 See also: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

During the 2019 outbreaks in the U.S. and the 2024 surges across Europe, we saw hospitals overwhelmed. When hospitals are full, the quality of care for everything drops. We’ve seen deaths in modern pediatric ICUs because sometimes, even with the best ventilators and fluids, the inflammatory response is just too much for a small body to handle.

The Vitamin A connection

One of the most fascinating (and vital) pieces of clinical knowledge regarding measles is Vitamin A. The WHO actually recommends that every child diagnosed with measles receive two doses of Vitamin A supplements. Why? Because the virus rapidly depletes the body’s stores of this vitamin.

Low Vitamin A leads to eye damage and blindness, but more importantly, it weakens the lining of the gut and lungs. This makes it easier for the virus to cause fatal damage. In many parts of the world, a simple supplement is the difference between life and death. Even in the U.S., doctors often check these levels in hospitalized kids because the deficiency can happen so fast.

What changed in the last few years?

You might be wondering why we are seeing more headlines about this lately. Honestly, it’s a mix of things.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted routine immunization schedules globally. Millions of kids missed their first or second dose of the MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) vaccine. On top of that, there has been a significant rise in vaccine hesitancy fueled by misinformation.

✨ Don't miss: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

When the vaccination rate in a community drops below 95%, the virus finds the gaps. It’s like a forest fire looking for dry brush. In 2024 and 2025, we saw massive spikes in cases in places like the UK, Romania, and parts of the Pacific Northwest in the U.S. These weren't just numbers on a screen; they were kids in oxygen tents.

Complications you don't hear about

Beyond death, the "morbidity"—the long-term health impact—is intense.

- Permanent blindness.

- Chronic ear infections leading to deafness.

- Severe diarrhea causing dangerous dehydration.

- "Croup" or severe laryngitis that can block the airway.

It’s a brutal virus. It doesn't care about your lifestyle or your organic diet. It’s a biological machine designed to replicate, and it does so by hijacking your cells.

Real talk: The vaccine works

The MMR vaccine is one of the most studied medical interventions in history. Two doses are about 97% effective at preventing the disease entirely. If you do catch it while vaccinated (a breakthrough case), it’s almost always incredibly mild—no pneumonia, no brain swelling, no death.

Before the vaccine was introduced in 1963, nearly every child caught measles. In the U.S. alone, that meant roughly 400 to 500 deaths every single year. Globally, it was millions. We’ve forgotten what that fear feels like, which is perhaps why some people feel comfortable skipping the shot. But the virus hasn't changed. It hasn't "weakened" over time. It’s the same killer it was sixty years ago.

Moving forward: What you should do

Understanding the risks is the first step. If you're wondering if you or your kids are safe, here is the checklist of what actually matters.

- Check your records: Most people born after 1968 in the U.S. received two doses. If you aren't sure, a simple blood test called a "titer" can check your immunity.

- Watch for symptoms: It starts like a cold—fever, cough, runny nose, and red eyes. The rash usually appears 3-5 days later, starting at the hairline and spreading down.

- Isolate immediately: If you suspect measles, do not just walk into a doctor's office or ER. Call ahead. They need to prep a room so you don't infect everyone in the waiting area.

- Support the vulnerable: If you are around infants or people with cancer, your immunity is their shield. This isn't just about your health; it's about the "herd."

- Trust the experts: Pediatricians see the complications firsthand. If they are worried about measles, it's because they've seen what it does to a child's lungs and brain.

Measles is a disease of "ifs." If we keep vaccination high, it stays away. If we let our guard down, people die. It’s that simple. While the world faces many complex health threats in 2026, this is one where we actually have the solution sitting in a vial. Using it is just a matter of remembering history so we don't have to repeat it.