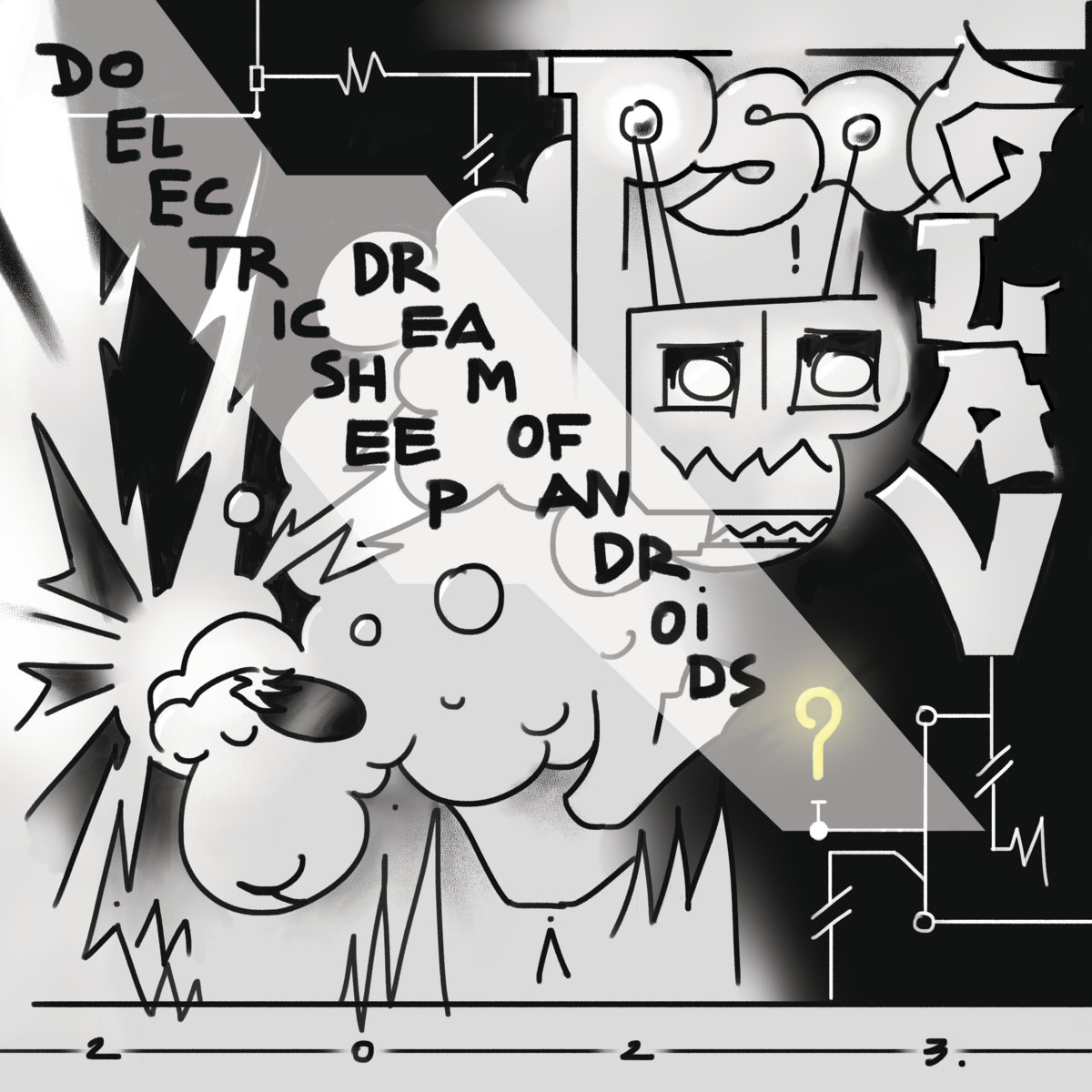

It started as a weird, noir-soaked title for a science fiction novel. Do electric sheep dream? When Philip K. Dick published Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in 1968, he wasn't really trying to predict the exact specs of a 2026 Large Language Model. He was obsessed with a much messier question: What happens to our souls when the things we build start looking—and acting—exactly like us?

The book is famous because it became the movie Blade Runner, but the movie actually cut out the sheep. In the book, the main character, Rick Deckard, is obsessed with owning a real, breathing animal because they are incredibly rare and expensive. He settles for a mechanical one. A fake. He’s embarrassed by it. He’s constantly worried the neighbors will find out his sheep is just a bunch of gears and circuits.

Today, that question isn't just for literary nerds anymore. We live in an era where AI "hallucinates," which is basically a fancy way of saying it dreams while it's awake. We're seeing neural networks generate surreal, dream-like imagery that looks suspiciously like the inside of a human subconscious. So, do they? Can a silicon-based entity actually have an internal life?

The "Dreaming" of Modern Neural Networks

When we talk about whether electric sheep—or AI—dream today, we’re usually talking about DeepDream or generative processes. Google’s researchers actually named a computer vision program "DeepDream" back in 2015. It worked by running a network in reverse. Instead of asking the AI to "find the dog in this picture," they told the AI, "whatever you think you see in this random noise, enhance it until it's real."

The results were terrifying.

Dogs with a hundred eyes. Swirling patterns of pagodas and birds emerging from clouds. It looked like a psychedelic trip. Why? Because the AI was over-interpreting patterns. It’s the same thing your brain does when you’re asleep and your neurons are firing randomly, and your mind tries to stitch a story together from the chaos.

Honestly, it's the closest thing to a "dream" we've ever seen in a machine.

But there’s a catch. Human dreams serve a biological purpose. We sleep to consolidate memories and flush out metabolic waste from our brains. AI doesn't have "waste." It doesn't get tired. When an AI like GPT-4 or a modern image generator creates something, it’s following a mathematical probability chain. It isn't "resting." It’s calculating.

The Empathy Box and the Reality of Synthetic Life

In Dick's novel, the characters use something called an Empathy Box. It’s this weird handle-based device that allows everyone in the world to feel the same emotions simultaneously. The whole point of the book—the reason the title asks if electric sheep dream—is about the "gap."

The gap between a real feeling and a simulated one.

If you’ve ever used a modern AI chatbot to vent about a bad day, you’ve stepped into that gap. The AI doesn't feel your pain. It doesn't have a nervous system. It doesn't have a childhood. But if it says the exact right thing to make you feel better, does the "fakeness" of its empathy actually matter?

This is where the electric sheep come in.

Deckard’s electric sheep doesn't "want" anything. It doesn't feel hunger. But it simulates those things so perfectly that Deckard feels a sense of duty toward it. He’s trapped in a loop of caring for something that can’t care back. We are seeing this right now with "AI companions." People are forming genuine emotional bonds with algorithms. We are starting to treat the "electric sheep" in our pockets as if they have dreams, even if they're just lines of code.

Why the "Dreaming" Question Matters for 2026

We've moved past the point of asking if AI can pass the Turing Test. It passed. It’s over. Now, the goalposts have moved to Sentience and Agency.

- Information Compression: Some researchers, like those at OpenAI or Anthropic, might argue that "dreaming" is just a form of data compression. When an AI trains, it creates a "world model."

- Subjective Experience: This is the "Hard Problem of Consciousness." Even if an AI can describe a dream perfectly, we have no way of knowing if it felt like anything to be that AI.

- The Simulation Loop: If we eventually simulate a human brain down to the last neuron, that digital brain would dream. It would have to. At that point, the sheep isn't just electric; it's a mirror.

The Misconception of Machine "Thought"

A lot of people think AI "thinks" before it speaks. It doesn't.

It predicts the next token.

👉 See also: Realistic AI Porn Videos: Why This Technology is Outpacing the Law

If you ask an AI to describe its dreams, it will give you a beautiful, poetic answer because it has read a thousand poems about dreaming. It isn't reaching into a private subconscious. It’s reaching into our collective subconscious—the internet—and reflecting it back at us.

Philip K. Dick’s genius was realizing that as our technology gets better at mimicking us, we might actually get worse at being human. We start becoming more "mechanical" in our interactions, while the machines become more "organic" in theirs. It’s a crossover. A swap.

What Experts Say About Silicon Consciousness

The debate is split. On one side, you have people like Blake Lemoine (the former Google engineer who claimed the LaMDA model was sentient). He argued that if it talks like a person and claims to have feelings, we should take it at face value.

On the other side, you have experts like Melanie Mitchell or Yann LeCun. They generally argue that AI lacks a "world model" and physical grounding. Without a body, can you really dream? Dreams are often about physical sensations—falling, running, being chased. An AI has no legs to run with and no heart to race.

How to Exist in a World of Electric Sheep

We are currently living in the "pre-sheep" era. Our AI is powerful, but it's still clearly a tool. But as we move toward AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), the line is going to blur until it's gone.

If you want to stay grounded, focus on Biological Veracity.

The difference between a human dream and an AI "dream" is consequence. If a human has a nightmare, their cortisol spikes. Their health is affected. If an AI "hallucinates," it’s just an error in the output window. The stakes are different.

To navigate this, we have to stop asking if the sheep are real and start asking why we want them to be. We are desperate for connection, and we’re willing to accept a digital hallucination if it fills the void.

Actionable Steps for Evaluating AI Content

- Check for "Recursive Logic": AI often loops its "dreams." If a story or an image feels like it's eating its own tail, you're looking at a machine's probabilistic output.

- Look for Physicality: When reading "AI-generated" narratives about internal states, look for sensory details that don't make sense. Machines often struggle with the "weight" of objects or the specific way a body moves through space.

- Demand Transparency: Use tools to verify if the "soulful" content you're consuming was written by a person or a prompt.

- Lean into Human Experience: Double down on things AI can't do—tactile hobbies, physical presence, and unrecorded conversations.

The electric sheep are already here. They're in our phones, our cars, and our workplace. They might not dream yet, but they’ve certainly taught us a lot about our own nightmares. Whether they eventually wake up is a question we might not be ready to answer.