Honestly, if you've ever sat through a high school biology class, you probably remember the teacher droning on about the "control center" of the cell. They likely told you that the nucleus is the brain of the operation, holding all the DNA in a neat little package. But here is the thing: when it comes to the most successful organisms on the planet, that rule doesn't apply.

So, do bacteria have a nucleus? The short answer is no. They don't. Not even a little bit.

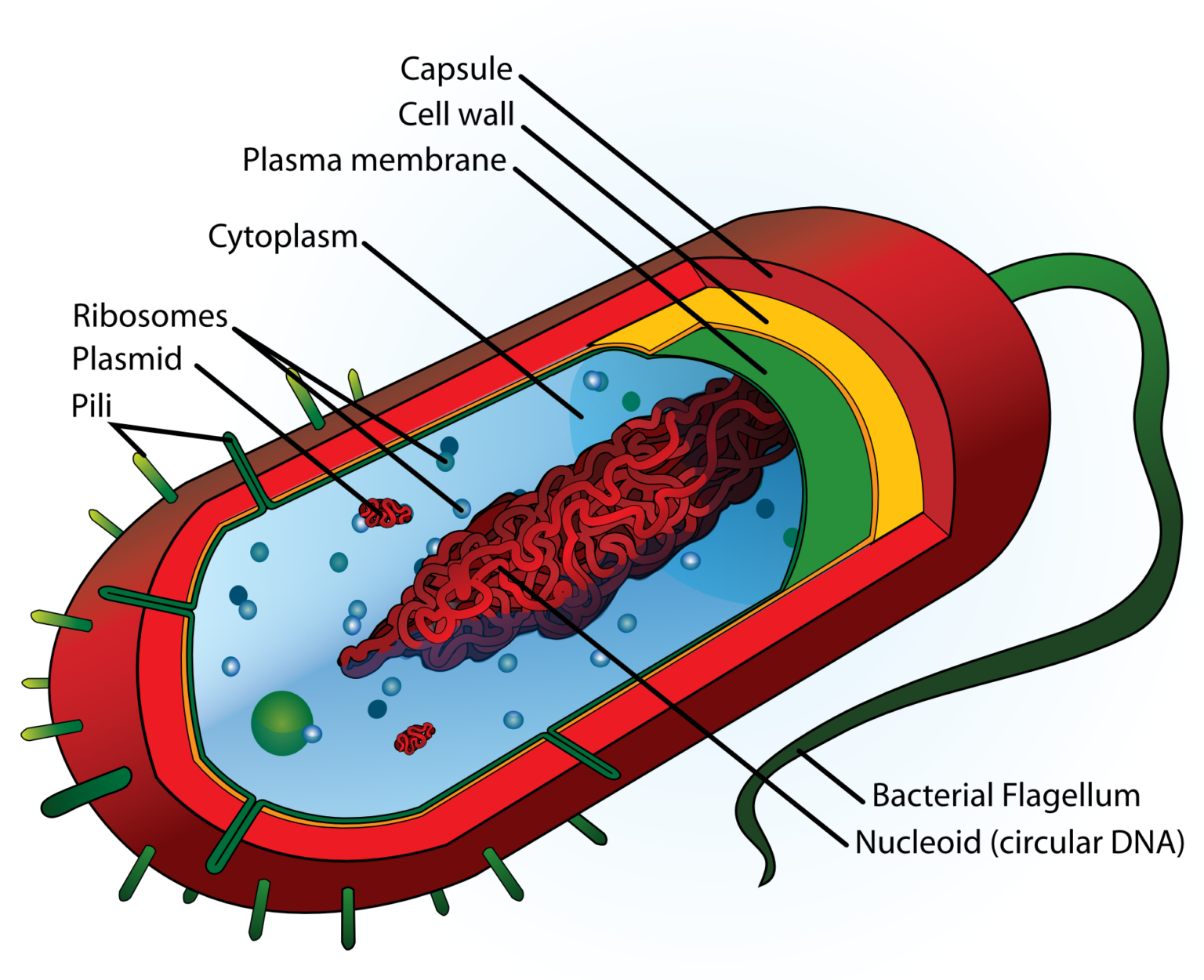

Bacteria are the ultimate minimalists of the biological world. While our cells—and the cells of plants, fungi, and even yeast—are like sprawling mansions with separate rooms (organelles) for different tasks, a bacterium is more like a studio apartment. Everything happens in one open space. There is no velvet rope or "VIP section" for their genetic material. This fundamental difference is what separates the prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) from the eukaryotes (everything else with complex cells).

The "Nucleoid" vs. The Nucleus

Just because bacteria lack a membrane-bound nucleus doesn't mean their DNA is just floating around like loose change in a dryer. That would be chaotic. Instead, they have something called a nucleoid.

The nucleoid is basically an irregularly shaped region within the cell where the genetic material sits. Think of it like a messy pile of yarn on a rug. It isn't boxed up, but it stays in its general area because of specific proteins that help keep it somewhat organized. In a human cell, the DNA is wrapped around proteins called histones. In bacteria, they use "nucleoid-associated proteins" (NAPs) to do a similar job, though the mechanics are different.

It’s actually pretty efficient. Since there’s no nuclear membrane, the machinery that reads the DNA and builds proteins can get to work immediately. In your cells, the instructions (mRNA) have to be shipped out of the nucleus before they can be read. In bacteria? It’s all happening at once. It’s like the difference between ordering a pizza and having it delivered (eukaryotes) versus just eating it while you're still in the kitchen (bacteria).

Why Doesn't a Bacterium Need a Nucleus?

Size matters here. Most bacteria are tiny. We are talking roughly 0.5 to 5.0 micrometers in length. When you are that small, things move around via simple diffusion. You don't need a complex shipping and receiving department (the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum) because everything is already right there.

🔗 Read more: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

But there is a bigger reason: speed.

Bacteria are built for rapid growth. Escherichia coli (E. coli), the famous gut resident, can double its population every 20 minutes under the right conditions. If it had to deal with the logistical nightmare of a nuclear envelope, it simply couldn't replicate that fast. By ditching the nucleus, bacteria have optimized for a "grow fast, die young, leave a billion copies" lifestyle.

The Weird Exceptions That Break the Rules

Science loves a good curveball. For decades, we thought the "no nucleus in bacteria" rule was absolute. Then we found the Planctomycetota.

Specifically, a bacterium called Gemmata obscuriglobus.

This little rebel has internal membranes that actually surround its DNA. For a long time, researchers like Ronald Fuerst argued this might be a true bacterial nucleus. It sparked a massive debate in microbiology. Is it a real nucleus? Or just a very fancy fold in the cell membrane? Most current research, including studies using 3D electron microscopy, suggests it’s not quite a "true" nucleus like ours, but it’s remarkably close. It shows that evolution isn't a straight line; it's more like a messy bush where different organisms find similar solutions to the same problems.

Plasmids: The Bonus Genetic Material

While we are talking about DNA, we have to mention plasmids. These are tiny, circular pieces of DNA that sit outside the main nucleoid.

💡 You might also like: Why the 45 degree angle bench is the missing link for your upper chest

If the main bacterial chromosome is the "instruction manual" for staying alive, plasmids are like "expansion packs" or "cheat codes." They often carry genes that provide a specific advantage, like resistance to antibiotics or the ability to digest weird chemicals.

Because there’s no nucleus to lock them away, bacteria can actually swap these plasmids with each other. It’s called horizontal gene transfer. It’s basically the bacterial equivalent of you shaking hands with a friend and suddenly knowing how to speak French. This is exactly how "superbugs" in hospitals spread antibiotic resistance so quickly. They don't wait for the next generation to evolve; they just trade the "resistance" plasmid like a Pokémon card.

How This Affects Your Health

Understanding that bacteria do not have a nucleus isn't just for passing a quiz. It’s the reason many of our best medicines work.

Take antibiotics like rifampicin. These drugs target the specific ways bacteria read their DNA. Because the bacterial machinery is different from yours (and because their DNA is "exposed" in the nucleoid), the drug can attack the bacteria without killing your own cells. If bacterial DNA were tucked away in a nucleus identical to ours, many of our current treatments would be far more toxic to the human body.

Breaking Down the Misconceptions

People often think "no nucleus" means "primitive." That’s a mistake. Bacteria have been around for about 3.5 billion years. They’ve survived every mass extinction the planet has thrown at them. They live in boiling volcanic vents, the freezing Antarctic ice, and, well, inside your stomach.

They aren't "simple." They are streamlined.

📖 Related: The Truth Behind RFK Autism Destroys Families Claims and the Science of Neurodiversity

By getting rid of the nucleus, they’ve managed to:

- Replicate at breakneck speeds.

- Adapt to new environments through rapid gene swapping.

- Keep their energy requirements low.

Real-World Evidence: The Endosymbiotic Theory

If you really want to understand the relationship between the nucleus and bacteria, you have to look at your own mitochondria. You might have heard they are the "powerhouse of the cell," but they were originally free-living bacteria.

Billions of years ago, a larger cell essentially "swallowed" a bacterium. Instead of digesting it, they formed a partnership. This is the Endosymbiotic Theory, championed by the brilliant biologist Lynn Margulis. The "swallowed" bacterium eventually became the mitochondria. This is why your mitochondria still have their own DNA, which—you guessed it—is circular and lacks a nucleus, just like modern bacteria.

Actionable Insights and Next Steps

Now that we've cleared up the "do bacteria have a nucleus" mystery, what do you actually do with this info?

- Reframe your view of "germs." Most bacteria aren't "trying" to make you sick; they are just following their biological programming to replicate as fast as possible in a nutrient-rich environment (which happens to be you).

- Respect the Antibiotic Course. Because bacteria lack a nucleus and can swap plasmids easily, they "learn" to fight drugs quickly. If you don't finish your prescribed antibiotics, you leave the "smartest" bacteria alive to trade their resistance genes with others.

- Probiotic Awareness. When you take probiotics, you are essentially introducing "good" prokaryotes into your system to compete for space with the "bad" ones. Their lack of a nucleus makes them highly reactive to their environment, which is why diet changes affect your gut microbiome so quickly.

- Deep Dive into Microbiology. If this weird world interests you, look up the work of Nick Lane or Ed Yong. They dive deep into how these microscopic, "nucleus-free" entities actually run the entire planet.

Bacteria might be "roommate-style" cells without a private nuclear office, but that simplicity is exactly why they are the most dominant life form on Earth. They don't need a nucleus to be complex; they just need a little DNA and a lot of speed.