You’re probably doing it right now without even realizing it. Whether you’re grabbing a coffee or shipping a package, you are part of a massive, invisible machine. Honestly, the division of labour meaning is way simpler than your high school economics textbook made it sound. It’s basically just the idea that if everyone does one specific thing really well, instead of everyone trying to do everything poorly, we all end up with more stuff and better lives.

Think about a simple pencil. No single human being on this planet knows how to make one from scratch. You’d need to mine graphite, cut cedar trees, smelt brass, and chemically engineer an eraser. It’s impossible for one person. But when we split those jobs up? We get millions of pencils for pennies.

What is the Actual Division of Labour Meaning?

At its core, the division of labour is the separation of a work process into a number of tasks, with each task performed by a separate person or group. It’s the backbone of modern civilization. Without it, you’d still be stitching your own shoes and hoping they don’t fall apart in the rain.

Adam Smith, the guy who basically invented modern economics, famously used a pin factory to explain this in his 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations. He noticed that one man working alone might struggle to make a single pin in a day. But in a factory where the work was split into eighteen distinct operations—one man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it—ten people could make 48,000 pins in a day. That’s a massive jump in productivity.

But it’s not just about factories anymore. We see this in software development where one person writes the backend code, another does the UI, and a third manages the cloud infrastructure. It’s also in your local restaurant. The "front of house" handles customers while the "back of house" handles the grill. If the chef had to stop cooking to go seat a table, your steak would be a hockey puck.

🔗 Read more: US Stock Futures Now: Why the Market is Ignoring the Noise

Why We Became Specialists

Specialization is the natural byproduct of this division. When you do the same thing over and over, you get fast. Scary fast. You develop what experts call "tacit knowledge"—those little tricks and muscle memories that can’t be taught in a manual.

There are three main reasons why splitting up tasks works so well:

- Skill Improvement: Practice makes perfect. Simple as that.

- Time Saving: You don’t lose time switching from one tool to another or moving from one station to the next.

- Innovation: When someone focuses on one tiny part of a process, they’re way more likely to figure out a better, faster way to do it or even invent a machine to do it for them.

It’s about efficiency. But it’s also about trade. Because I’m a writer and you’re (maybe) an accountant or a nurse, I can trade my words for your services. We both win because we’re both doing what we’re best at.

The Dark Side of Doing One Thing

It’s not all sunshine and productivity gains. Karl Marx had some pretty strong feelings about this, and honestly, he had a point. He argued that the division of labour meaning often led to "alienation."

💡 You might also like: TCPA Shadow Creek Ranch: What Homeowners and Marketers Keep Missing

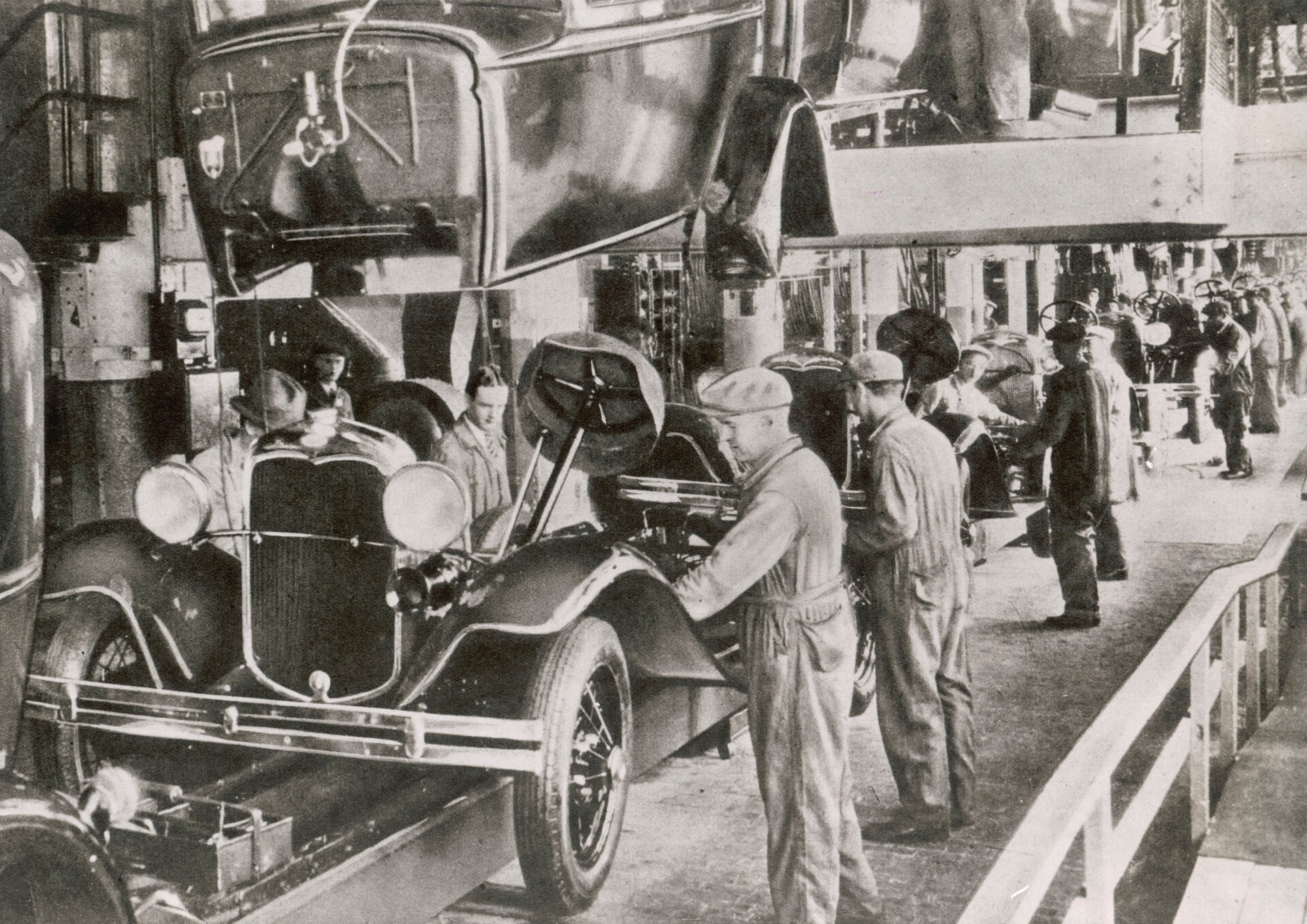

When you spend ten hours a day just tightening one specific bolt on a car assembly line, you lose your connection to the final product. You aren't a craftsman anymore; you’re just a "cog in the machine." This can lead to a total lack of job satisfaction. Smith even worried about this himself, fearing that people would become "as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become" if their work was reduced to a few simple, repetitive tasks.

Then there's the risk of "deskilling." If a job is broken down into tiny, brainless steps, the employer doesn't need to pay for a skilled artisan. They can hire anyone off the street for minimum wage. This creates a power imbalance.

Modern Variations: Global and Digital

Today, the division of labour has gone global. This is what people usually mean when they talk about "supply chains." Your iPhone isn't just "made in China." It’s designed in California, uses chips from Taiwan, camera lenses from Germany, and cobalt mined in the Congo.

We also see it in the "gig economy." Platforms like Upwork or Fiverr are basically massive marketplaces for specialized tasks. Instead of hiring a full-time marketing person, a small business might hire one person to write a blog, another to design a logo, and a third to run their Facebook ads. It’s the division of labour, but unbundled from the traditional 9-to-5 job.

📖 Related: Starting Pay for Target: What Most People Get Wrong

Different Types You Should Know

- Social Division: This is the big picture. It’s how society splits up into occupations like doctors, farmers, and teachers.

- Technical Division: This happens inside a single firm or factory. It’s the "assembly line" model.

- Territorial Division: When certain regions specialize in certain goods. Think Napa Valley for wine or Silicon Valley for tech.

Is the Division of Labour Dying?

Surprisingly, some people think we might be moving backward—or at least sideways. With the rise of AI and automation, those repetitive tasks Smith talked about are being handled by robots. This is forcing humans back toward being "generalists" who can manage multiple systems, or "super-specialists" who do the high-level creative work machines can't touch.

Multi-tasking is often seen as a virtue now, but it’s actually the enemy of the division of labour. When you jump between emails, a spreadsheet, and a Zoom call, your productivity drops by about 40%. We’re fighting against the very thing that made the industrial revolution possible.

How to Use This in Your Own Life

Understanding the division of labour meaning isn't just for economists; it’s a productivity hack for your actual life.

- Audit your "switching costs." Stop trying to do five different types of tasks in one hour. Batch your deep work.

- Outsource the low-value stuff. If your time is worth $50 an hour and you’re spending two hours a week mowing the lawn for "free," you’re actually losing $100. Hire a teenager and spend those two hours doing what you’re actually good at.

- Identify your "Niche." In a globalized world, being a generalist is dangerous. Be the best at one specific, valuable thing.

- Watch for burnout. If your job has become too specialized and you feel like a robot, you need to find ways to reconnect with the "whole" of what you’re creating.

The division of labour is why we aren't all living in huts trying to figure out how to make fire. It’s the engine of wealth. But like any engine, if you run it too hard without maintenance, things start to break. Keep your specialization sharp, but don't let it turn you into a machine.

Next Steps for Implementation

- Map Your Workflow: Write down every task you did today. Group them into "types" (admin, creative, communication).

- Identify Your Pin: Find the one task that produces the most value for you—your version of "drawing out the wire."

- Protect Your Time: Block out four hours twice a week where you do only that high-value task, ignoring all other divisions of your job.

- Evaluate Your Tools: Look for one piece of software or a service that can take a repetitive, low-skill task off your plate entirely.