Ever looked at a cliffside and thought it looked like a giant, messy layer cake? Geologists do this for a living. They stare at these stacks of rock, called strata, to read the history of the Earth. But sometimes, the cake is missing a whole layer of frosting and sponge. You’re looking at one layer of rock, and the one sitting right on top of it is actually millions of years younger. There’s a gap. A literal hole in time. This specific kind of "missing time" is called a disconformity.

It’s weird.

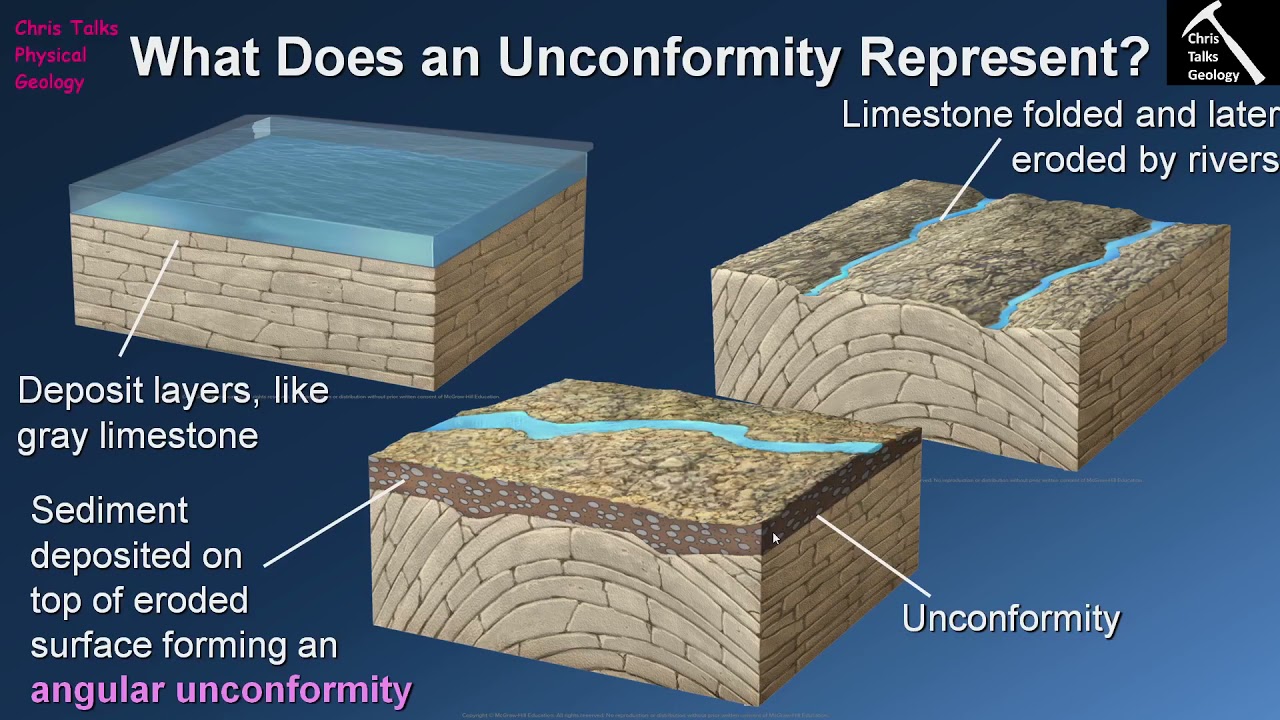

Usually, when we think of geological gaps, we imagine dramatic, tilted rocks crashing into flat ones. That’s an angular unconformity. But a disconformity is sneaky. It’s a hidden break in the sedimentary record where the layers above and below the gap are still parallel. They look perfectly fine. They look like they belong together. But they don't. You might be standing on a limestone bed from the Devonian period, and the sandstone directly touching it started as beach dunes in the Cretaceous. Where did the 250 million years in between go?

Spotting the Invisible Gap

If you aren't looking closely, you’ll miss it. Because the layers stay parallel, a disconformity doesn't scream for attention like other geological features do. It’s the "silent" unconformity. To find it, you usually need a microscope or a very keen eye for fossils.

👉 See also: Marshalls Wayne New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Think about the Grand Canyon. It’s the world’s best textbook for this stuff. Within those red and orange walls, there are massive disconformities. The Redwall Limestone and the Temple Butte Formation look like a continuous sequence of deposition, but there is a massive time jump between them. Geologists call these "paraconformities" if the gap is nearly impossible to see without dating the rocks, but generally, we’re talking about an erosional surface.

Something happened. Either the land rose up and the wind and rain scrubbed away the top layer, or the sea level dropped and stopped depositing new mud altogether.

Essentially, you have three stages:

- Sediment settles at the bottom of a sea or lake. It hardens into rock.

- The area is uplifted or the water dries up. Erosion begins. Rain, rivers, and wind eat away at the surface. This creates an uneven, rugged top.

- The area sinks again or the sea returns. New sediment drops right on top of that rugged surface, filling in the old cracks.

Because the new layers are laid down flat on a surface that was also once flat (even if it got a bit bumpy from erosion), the horizontal "stacking" looks consistent. It’s like taking a book, ripping out chapters five through twelve, and gluing chapter thirteen directly to chapter four. The page numbers don't match, but the book still closes flat.

Why Does This Actually Matter?

It matters because of oil, water, and climate.

When there’s an erosional surface like a disconformity, it often creates "vuggy" space—basically little caves and holes in the rock. If you are an oil company looking for a reservoir, these gaps are gold mines. They are porous. They hold fluids. If you don't understand where the disconformity is, you might drill into a solid block of rock and find absolutely nothing, while a few hundred yards away, the "missing" time has created a massive pocket of natural gas.

From a climate perspective, these gaps are a nightmare for researchers. If you’re trying to track how carbon dioxide levels changed over 500 million years, a disconformity is a corrupted file in your hard drive. It’s a period where the Earth "forgot" to save its progress.

James Hutton, the father of modern geology, was the first to really grapple with these gaps at places like Siccar Point. While he was focusing on angular unconformities, his work paved the way for us to realize that the Earth is way, way older than we thought. If we see these massive gaps where rock should be but isn't, it implies that the Earth has gone through endless cycles of birth and destruction.

The Fossil Problem

Biostratigraphy is usually how we catch a disconformity in the act. Imagine you’re looking at a layer of rock full of trilobites. Simple, crunchy little sea bugs. Then, in the very next centimeter of rock above it, you find the teeth of a primitive mammal.

Trilobites went extinct about 252 million years ago. Primitive mammals didn't show up in that form until much later.

The fossils tell the truth. Even if the rock looks like one continuous unit, the "evolutionary jump" is too big. You’ve found a disconformity. You've found a place where the geological clock stopped ticking—or rather, where the clock kept ticking but the hands were ripped off.

How to Tell a Disconformity Apart from its "Cousins"

Geology loves jargon. It’s easy to get confused.

- Nonconformity: This is when sedimentary rock sits on top of igneous or metamorphic rock (like granite). It’s a total mismatch of rock types.

- Angular Unconformity: The old rocks are tilted at an angle, and the new ones are flat on top. This is the easiest one to see from a car window.

- Disconformity: The layers are parallel. The only way to know there's a gap is by looking at the erosion surface or the fossils.

- Paraconformity: This is the "pro level" disconformity. There is no visible erosion. The layers look like they were laid down five minutes apart, but the fossil record says it was fifty million years.

Honestly, identifying a paraconformity is one of the hardest tasks in field geology. You need to send samples to a lab for radiometric dating or find microscopic "index fossils" (like pollen or tiny shells called foraminifera) to prove the time gap exists.

Real World Example: The Ozark Plateau

In parts of Missouri and Arkansas, the geology is relatively flat. You might see a bluff of limestone that looks uniform. However, if you're a specialist, you'll notice that the Mississippian-age rocks are sitting directly on top of Ordovician-age rocks.

That is a gap of nearly 100 million years.

During that time, the area was likely a high-standing plain. No new rocks were forming. The rocks that were there were being chewed up by the elements. When the oceans finally crept back over the middle of North America, they dumped new limey mud on top of a surface that had been exposed to the air for an eternity. The result? A disconformity that covers thousands of square miles but is almost invisible to the naked eye.

Actionable Insights for Rock Hounds and Students

If you’re out hiking or studying for a geology quiz, don't just look at the color of the rocks. Look at the "contacts"—the lines where two types of rock meet.

- Check for "Basal Conglomerates": Right at the line of a disconformity, you’ll often find chunks of the older rock embedded in the newer rock. These are pebbles that were sitting on the ground when the new sediment arrived.

- Look for uneven lines: If the contact line between two horizontal layers looks wavy or jagged like a saw blade, you’re likely looking at an old erosional surface.

- Fossil hunting: If you find a layer with sea shells and the layer directly above it has land plants, you’ve found a major environmental shift that often signals an unconformity of some kind.

- Use State Geologic Maps: Most people don't realize that every state has a detailed map showing the age of the bedrock. If you see two different colors touching on the map that represent wildly different eras (like "O" for Ordovician and "D" for Devonian), go to that spot. You’re looking for a disconformity.

Understanding these gaps changes how you see the world. You realize that the ground beneath your feet isn't a solid, unbroken record. It’s a fragmented story. It’s a diary with half the pages missing, and the "missing" parts are just as important as the ones we can actually read.

Start by visiting a local roadcut. Look for those horizontal lines. If you see a sharp, irregular break between two flat layers, you aren't just looking at rock. You're looking at a ghost of a landscape that vanished millions of years ago.