Imagine a public square in 1757 Paris. A man named Robert-François Damiens is about to be executed for trying to kill King Louis XV. The scene is horrific. His flesh is torn away with red-hot pincers, his hand is burned with sulfur, and eventually, four horses pull his body into pieces.

Michel Foucault starts his masterpiece, Discipline and Punish, with this exact, stomach-churning description. It’s a shock to the system. But why did he start there? He wasn't just trying to be edgy or gross us out. He was showing a massive shift in how the world works. Within eighty years, that kind of public, bloody spectacle basically vanished. It was replaced by something much quieter, much more boring, and—if you ask Foucault—much more terrifying: the modern prison.

Honestly, most people think the move from public torture to private jail cells was just "human progress." We got nicer, right? Foucault says no. He argues we didn't get more "humane"; we just found a more efficient way to control people. Instead of breaking the body, the state started trying to "fix" the soul.

The Birth of the Modern Soul

Foucault’s central argument in Discipline and Punish is that power changed its shape. In the old days, power was "sovereign." The King had to show his face and his strength. If you broke the law, you offended the King personally, and he’d crush you to prove he was still the boss. It was loud. It was messy.

Then came the "disciplinary" era.

This isn't about one guy in a crown. It's about a sprawling web of experts—doctors, psychiatrists, wardens, and teachers. They don't want to kill you. They want to train you. They want to turn you into what Foucault calls a "docile body." This is basically someone who is useful, obedient, and fits perfectly into the machinery of capitalism. Think about your school days. The bells, the rows of desks, the permission to pee, the constant grading. That’s discipline. It’s not about being "good"; it’s about being predictable.

It’s kinda wild when you realize that Foucault sees the school, the hospital, the factory, and the prison as essentially the same building with different names. They all use the same tricks to keep us in line.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The Panopticon: You Are Always Being Watched (Or Might Be)

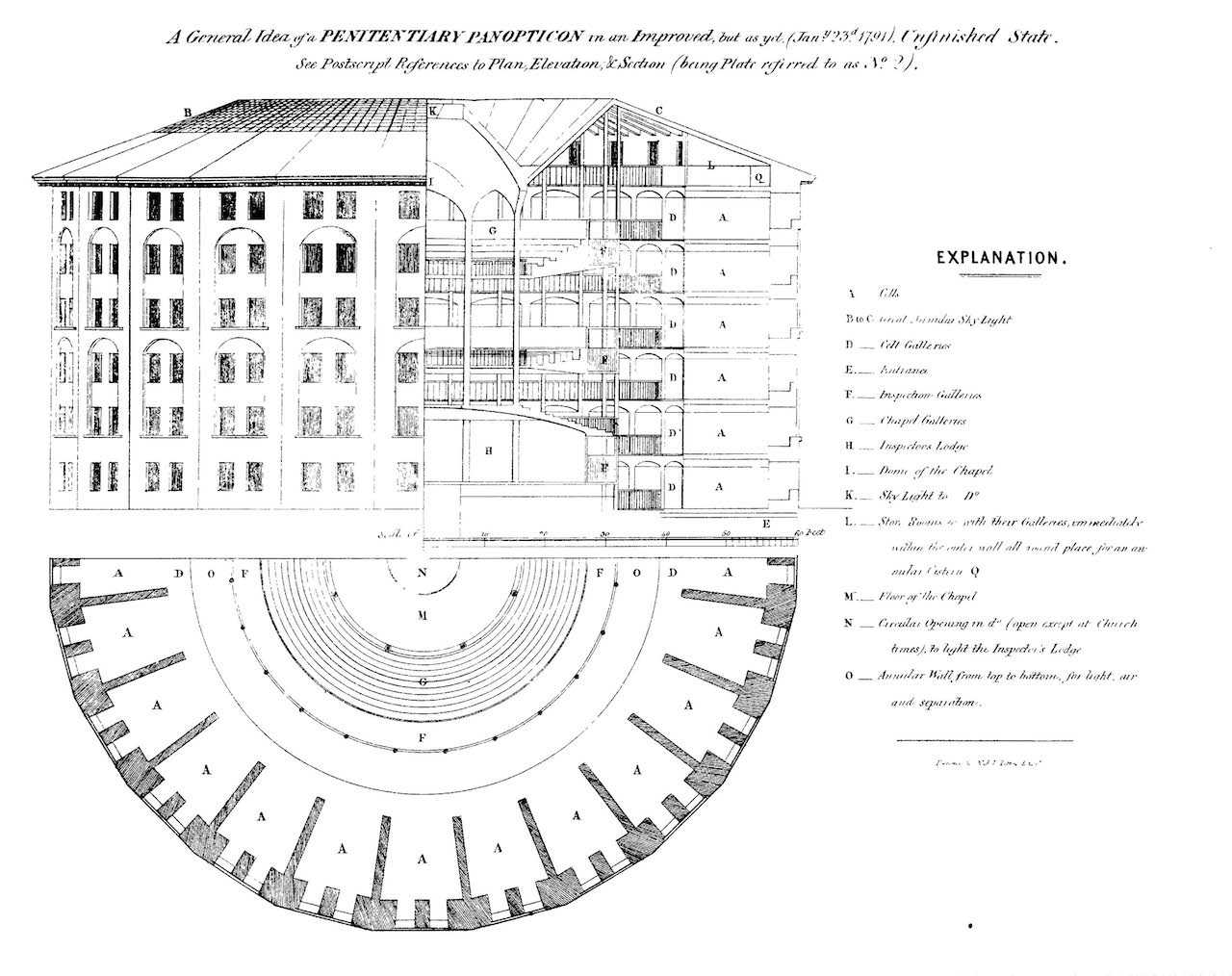

If you’ve ever felt like you’re being watched while walking through a store with cameras, you’ve experienced the Panopticon. This is the most famous part of Discipline and Punish. Foucault borrows an architectural idea from Jeremy Bentham, a philosopher who designed a circular prison where one guard in a central tower could see into every cell.

The kicker? The prisoners can’t see into the tower.

They never know if the guard is actually looking at them or taking a nap. Because they might be watched, they start watching themselves. They internalize the guard. They become their own jailer.

This is the "automatic functioning of power." You don’t need a whip if the person is already disciplining themselves because they’re afraid of being caught. In the 21st century, we don’t even need the stone tower anymore. We have algorithms, "likes," credit scores, and Ring doorbells. We are living in a digital Panopticon where we constantly curate our lives to look "normal" or "productive" because the gaze of the "tower" (the internet/state/employers) is everywhere.

Why "Discipline and Punish" Hits Different in 2026

You’d think a book about 18th-century French prisons would be dusty. It’s not. It’s actually the blueprint for understanding why we feel so burnt out today.

Foucault talks about "The Examination." This is the process where power turns you into a "case." Think about how much data is collected on you daily. Your steps, your sleep quality, your productivity metrics at work, your search history. We are constantly being measured against a "norm."

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

- If you sleep too little, you’re an outlier.

- If you work too slowly, you’re a problem.

- If your BMI is off, you’re a "patient."

This "normative power" is subtle. Nobody is forcing you at gunpoint to track your calories or get a 4.0 GPA, but the pressure to be "normal" is so heavy it might as well be a physical weight. Foucault points out that this is how modern society maintains order. We don't punish people for being "evil" as much as we try to "correct" them for being "abnormal."

The Illusion of the "Gentle" Reformer

A lot of historians look at prison reformers like John Howard or Elizabeth Fry as heroes of mercy. Foucault isn't so sure. He acknowledges they wanted to stop the cruelty of the old dungeons, but he argues their "reforms" actually extended the reach of the state.

When execution was the main punishment, the state only cared about you for the ten minutes it took to kill you. The rest of the time, you were mostly left alone. Once the "reformers" brought in the penitentiary, the state suddenly cared about your thoughts, your habits, your sexuality, and your childhood. The "humanization" of punishment was actually the expansion of control into the most private parts of the human mind.

It’s a trade-off. We traded the occasional, terrifying violence of the King for the constant, nagging "management" of the bureaucracy.

Resistance Isn't What You Think It Is

One of the most frustrating (and brilliant) things about Foucault is that he doesn't give you a simple "out." There’s no big revolution that fixes everything because power is everywhere. It’s in the way we talk, the way we study, and the way we treat our bodies.

But he does suggest that by understanding these "micro-physics of power," we can start to resist in small ways. Resistance, for Foucault, often means refusing to be what the system wants you to be. It's about rejecting the "labels" and "norms" that experts try to pin on you.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

If the goal of discipline is to make us "docile" and "useful," then perhaps the greatest act of rebellion is being "useless" or "unpredictable" on your own terms.

Actionable Insights: Breaking the Disciplinary Cycle

So, how do you actually use Discipline and Punish in your real life? It’s not about burning down a prison; it’s about auditing how power works on you.

1. Audit your "Internalized Guard" Next time you feel a pang of guilt for not being "productive" on a Saturday or for not looking "perfect" on social media, ask yourself: Who is the guard in the tower? Realize that the "norm" you are trying to meet is often a construct designed to make you a more efficient "unit" for someone else.

2. Question the "Expert" Label Foucault was wary of anyone claiming to have the "scientific truth" about human behavior. When a lifestyle coach, a corporate manager, or a social media algorithm tells you how you "should" function, recognize it as an exercise of power. You aren't a "case study"; you're a person.

3. Recognize the Architecture of Control Look at the spaces you inhabit. Your open-office plan at work? That’s a Panopticon designed for "visibility." Your fitness tracker? That’s a "cell" of data collection. By seeing these things for what they are—tools of discipline—you can start to detach your self-worth from the metrics they produce.

4. Protect the "Abnormal" The system survives by marginalizing the "abnormal." Foucault’s work encourages us to be skeptical of "correction." Instead of trying to "fix" people who don't fit the mold, we should question why the mold exists in the first place.

Discipline and Punish is a dark book, but it’s also liberating. It reminds us that the "way things are" isn't natural or inevitable. It was built. And if it was built, it can be questioned. We might live in a world of cameras and "norms," but knowing how the trap works is the first step to stepping out of it.

Final Thoughts on Foucault's Legacy

Foucault died in 1984, long before the iPhone or the "surveillance capitalism" of the 2020s. Yet, his analysis of how power uses "visibility" to control us feels like it was written yesterday. He correctly predicted that the "carceral" logic of the prison would eventually leak out and soak into every corner of society. Today, we don't just live in a society that has prisons; we live in a society that is a prison-like structure of constant monitoring and "normalization." Understanding this doesn't make the cameras go away, but it does give you your mind back.