Imagine walking into a room where twenty-five people are all trying to learn how to bake a sourdough loaf. One person has been a professional pastry chef for a decade. Another has never cracked an egg. A third person is allergic to gluten, and a fourth doesn't speak English very well. If you stand at the front and read the exact same recipe at the exact same speed to all of them, most of that room is going to fail. The chef will be bored to tears, the novice will be panicked, and the gluten-intolerant student is basically wasting their time.

This is the fundamental problem with the "factory model" of education. It treats kids like a homogenous heap of raw material. Differentiated instruction is the antidote to that mess.

Honestly, it’s not some new-age fad or a complex algorithm. It’s just the common-sense realization that kids aren't robots. They come with different "operating systems." Some are visual learners, some have ADHD, and some are just having a really bad Tuesday because they skipped breakfast. Carol Ann Tomlinson, who is basically the godmother of this entire movement, defines it as a way of teaching where you proactively modify your curriculum, your teaching methods, and your resources to reach every kid. It's about being flexible. It’s about being human.

What Differentiated Instruction Isn't (The Big Misconceptions)

People get this wrong all the time.

Some teachers hear the term and immediately want to quit because they think it means writing thirty different lesson plans for thirty different kids. That’s impossible. You'd burn out in a week. Differentiated instruction isn't about individualized instruction in that way. It’s not a "personal tutor" model where the teacher is a short-order cook making thirty different meals.

It’s also not just "grouping the smart kids together." That’s tracking, and it usually ends up being pretty discriminatory. Real differentiation is fluid. You might group kids by interest one day, by skill level the next, and then have them work totally solo the day after that. It’s also definitely not just giving the fast workers "more" work. If a kid finishes their math sheet in five minutes, giving them ten more of the same problems isn't teaching; it's a punishment for being fast.

The Four Pillars: Content, Process, Product, and Environment

If you want to actually do this without losing your mind, you have to look at the four levers you can pull. Teachers call these the "elements" of differentiation.

1. The Content (The "What")

This is what the students are learning. Now, you usually can't change the state standards—the "what" is often set in stone by the school board. But you can change how students access that information.

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

For example, if you're teaching a unit on the Civil War, some students might read a traditional textbook chapter. Others might listen to a podcast or watch a documentary. A student with dyslexia might use text-to-speech software. The goal is the same—understanding the causes of the war—but the "entry point" is different. You're leveling the playing field.

2. The Process (The "How")

This is the "meat" of the lesson. How do the kids make sense of the ideas? This is where you see things like "tiered activities."

Think about a math class learning about ratios.

- Group A might work with physical blocks (manipulatives) to see the ratio in 3D.

- Group B might be solving word problems about sports statistics.

- Group C might be applying ratios to a complex architectural blueprint.

Everyone is doing math. Everyone is working on ratios. But the "how" is tuned to their current "readiness level." It's about finding that "Goldilocks Zone"—not too easy, not too hard.

3. The Product (The Evidence)

This is my favorite part. How does the student show you they actually learned the thing?

In a traditional classroom, you take a test. In a differentiated classroom, a student might write an essay, sure. But another might build a 3D model, record a video presentation, or create a detailed infographic. If the goal of the lesson is to demonstrate an understanding of "biodiversity," does it really matter if they show that through a poem or a lab report? Probably not. By giving kids a choice in the product, you're tapping into their natural strengths.

4. The Environment (The Vibe)

The physical and psychological space matters. Some kids need a silent corner with noise-canceling headphones to think. Others work best in a "collaboration station" where they can talk through ideas. Differentiation means the room doesn't have to look like a graveyard where everyone sits in silent rows. It can be a bit messy. It can be loud.

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

The Science of Why This Works

It’s not just "nice" to do this; it’s backed by neuroscience. The brain has three primary networks involved in learning: the recognition network (the "what"), the strategic network (the "how"), and the affective network (the "why" or the engagement).

When a student is forced to do work that is way above their "readiness" level, their amygdala—the brain's fear center—kicks in. They go into "fight or flight" mode. They stop learning. Conversely, if the work is too easy, the brain essentially turns off. Differentiated instruction keeps the brain in the "Zone of Proximal Development," a term coined by psychologist Lev Vygotsky. It’s that sweet spot where a student is challenged just enough to grow, but not so much that they break.

Real-World Classroom Examples

Let's look at a 4th-grade science unit on ecosystems.

The teacher, let's call her Mrs. Gable, knows she has a wide range of readers. Instead of one article, she uses a tool like Newsela to provide the same news story about "The Everglades" at five different reading levels. This is differentiation of content.

Then, during the lesson, she uses "choice boards." This is a 3x3 grid of activities. Students have to pick three to complete a "tic-tac-toe." Options include:

- Drawing a food web.

- Writing a "day in the life" story of an alligator.

- Researching a local invasive species.

- Building a terrarium.

One kid who struggles with writing but loves art picks the drawing and building options. They stay engaged for 45 minutes straight. No behavior issues. No "I'm bored." That’s the magic of it.

The Struggle is Real (The Hard Truths)

Let's be real for a second. This is hard.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

It takes more prep time. It requires a teacher who is incredibly organized and good at "classroom management." If you don't have a handle on your students' behavior, trying to have four different things happening at once is a recipe for a riot.

Also, many teachers feel pressured by standardized testing. They worry that if they aren't teaching "to the middle" on the exact same schedule, their scores will drop. But ironically, the data usually shows the opposite. When kids are met where they are, they actually perform better on those big tests because they haven't spent the year "checked out" or feeling stupid.

How to Start (Actionable Steps)

If you're an educator or even a parent looking to advocate for this, you don't have to flip the whole system overnight. Start small.

Step 1: Get the Data. You can’t differentiate if you don't know your kids. Use "exit tickets"—small slips of paper where kids answer one question at the end of class. This tells you immediately who got it and who didn't. No more guessing.

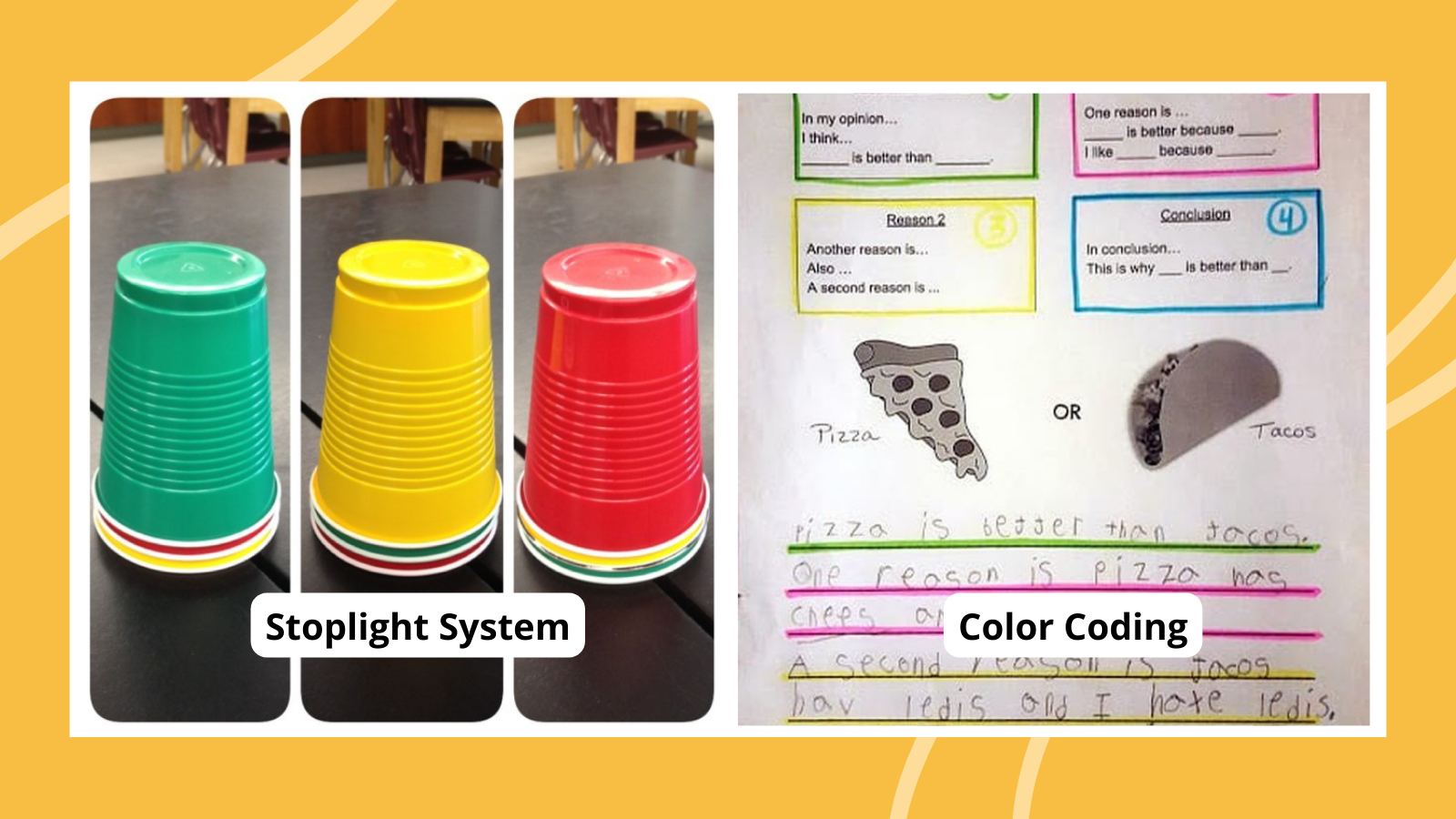

Step 2: Flexible Grouping. Stop thinking of "the high group" and "the low group." Instead, group kids by interest. If you're teaching persuasive writing, let the "video game kids" write a pitch for a new console and the "animal kids" write a plea for a local shelter. The skill is the same; the motivation is different.

Step 3: The "Think-Pair-Share" Upgrade. Instead of just asking a question to the whole class, give them thirty seconds of "think time" (great for introverts), then have them "pair" with a neighbor (great for English Language Learners to practice), then "share" with the class. This is a tiny, zero-prep way to differentiate the process.

Step 4: Use Technology Wisely. Tools like Khan Academy or Duolingo are built-in differentiation. They move at the student's pace. If a kid gets it, the app moves them on. If they don't, it gives them more practice. Use these tools as "stations" while you work one-on-one with a small group that’s struggling.

Ultimately, differentiated instruction is about seeing the human in the desk. It’s about realizing that a "one-size-fits-all" education actually fits nobody. It takes a lot of heart, a fair amount of coffee, and a willingness to be wrong. But when you see a "struggling" student's eyes light up because they finally got a "product" they're proud of, you realize there's no going back to the old way.

Focus on the "Small Wins" first. Pick one lesson next week. Change just one thing—the reading level, the seating, or the final project options. See what happens to the energy in the room. That's where the real change begins.