Bamboo is weird. It’s a grass, not a tree, yet it can grow taller than a house in a single season. Most people walk into a garden center, see something green and "zen," and buy it without realizing they might be planting a botanical landmine or, conversely, a plant that will just sit there and sulk for three years. If you’ve ever looked at the different types of bamboo available, you know it’s a mess of Latin names and conflicting advice.

Stop thinking about bamboo as one thing. It’s actually over 1,400 species.

Some will eat your neighbor's yard. Some will die if the temperature hits freezing. Others are basically indestructible. Understanding the nuances between running and clumping varieties—and the specific sub-species within them—is the difference between a beautiful privacy screen and a lifelong legal battle with the city over cracked pavement.

The Running vs. Clumping War

This is where everyone messes up.

If you remember one thing, make it this: Running bamboo (Leptomorph) has underground rhizomes that act like heat-seeking missiles. They travel horizontally and pop up wherever they want. This is the stuff of nightmares for suburban homeowners. Clumping bamboo (Pachymorph) stays in a tight circle. It grows outward from the center, slowly, like a bunch of tall grass.

Why would anyone ever plant a runner? Honestly, because they grow faster and create that "wall of green" look in half the time. If you have a massive property in a place like the Pacific Northwest, a grove of Phyllostachys aureosulcata (Yellow Groove) is stunning. But if you’re on a 5,000-square-foot lot in the suburbs, you’re playing with fire. Unless you install a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) root barrier at least 24 inches deep, that runner is going to find its way under your fence. It just will.

Clumpers are safer. Period. Species like Bambusa oldhamii are iconic for a reason. They get big, they look tropical, and they won't end up in your pool filter. But clumpers are usually less cold-hardy. You’ve got to match the biology to your zip code or you’re just throwing money away.

💡 You might also like: Dutch Bros Menu Food: What Most People Get Wrong About the Snacks

Cold-Hardy Giants: The Survivors

Most people think bamboo only grows in the tropics. Wrong.

There are different types of bamboo that thrive in the mountains of China and the chilly parts of the United States. Take the Fargesia genus. These are the gold standard for cold-hardy clumping bamboo. They are "mountain bamboos." They hate extreme heat. If you live in Georgia, a Fargesia murielae (Umbrella Bamboo) will probably shrivel and die from heat stress. But if you're in Chicago or New York? It’s a champ.

The Fargesia nitida is another one. It’s elegant, has slightly purple-toned canes (culms), and can handle temperatures down to -20°F. That’s insane for a plant that looks like it belongs in a rainforest.

Timber Bamboos: When Size Matters

If you want the "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" look, you’re looking for timber bamboo. These are the giants. Phyllostachys edulis, commonly known as Moso bamboo, is the big kahuna. It’s the stuff they use for flooring and textiles. In the right conditions, it can reach 75 feet in height with diameters of 7 inches.

Moso is a runner. Don't forget that.

The problem with Moso is that it’s finicky. It needs a very specific climate—hot, humid summers and mild winters. People try to grow it in California and wonder why it stays small. It’s because the humidity isn't there. If you want a giant clumper instead, go for Bambusa balcooa. It’s a beast from India. It’s thick-walled and used for construction. It won't run away, but it will take up a 10-foot circle in your yard within a decade. Plan accordingly.

📖 Related: Draft House Las Vegas: Why Locals Still Flock to This Old School Sports Bar

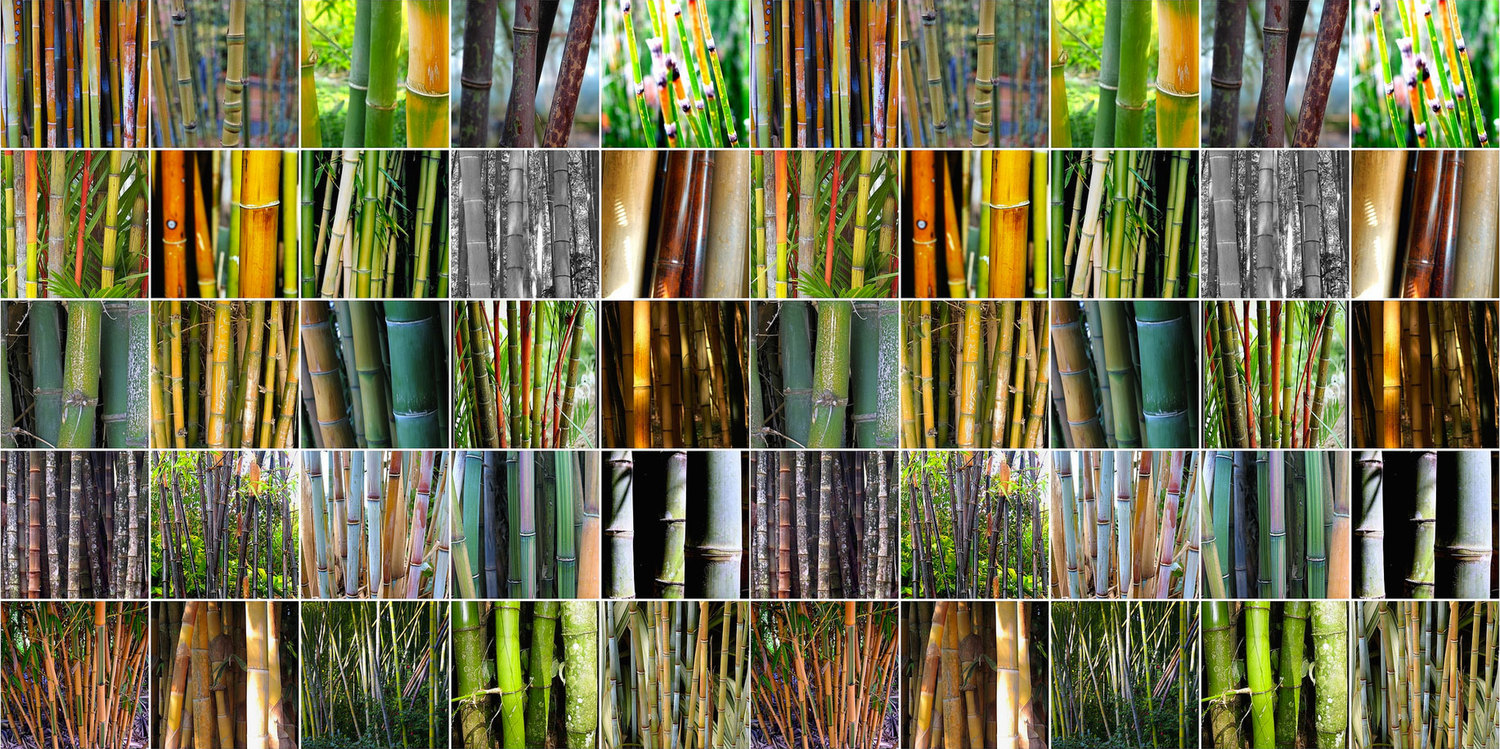

The Aesthetic Outliers: Black, Blue, and Striped

Sometimes you don’t want a forest; you want a statement.

- Black Bamboo (Phyllostachys nigra): This is arguably the most famous ornamental. The canes start green and turn a jet, polished black over two years. It’s a runner, but it’s a "polite" runner—it moves slower than its cousins. Still, keep it in a pot or behind a barrier.

- Blue Bamboo (Himalayacalamus hookerianus): Yes, it’s actually blue. Well, it’s a powdery, cool-toned teal. It’s a clumper. It’s breathtaking. It’s also incredibly sensitive to frost. If you live in a coastal, frost-free zone, it’s the ultimate "flex" plant.

- Buddha’s Belly (Bambusa ventricosa): This one is weird. If you stress it out—give it barely enough water—the spaces between the nodes (the "joints" of the bamboo) swell up like little bellies. If you give it plenty of water and fertilizer, it just grows straight and tall, losing its unique look. It’s a masterclass in how environment dictates form.

Living with the Different Types of Bamboo

You can't just plant bamboo and walk away. That’s how "invasive species" horror stories start. Even the clumpers need maintenance.

Thinning is the secret. Every year, you should cut out the oldest canes. This isn't just for aesthetics. It lets light into the center of the clump and encourages the plant to put up thicker, healthier new shoots (culms). Use a sharp saw. Bamboo is high in silica—it’s basically natural glass—so it will dull your tools fast.

Watering is the other big thing. When bamboo is first planted, it’s a thirsty beast. Once established, it’s remarkably drought-tolerant, but if you want that lush, deep green color, you can’t let it bake in dry soil.

Mulch is your best friend. In the wild, bamboo drops its own leaves and creates a thick mat of mulch that keeps the roots cool and recycles silica back into the soil. Don’t rake up the leaves! Leave them there. They are the best fertilizer the plant could ask for.

Addressing the "Invasive" Myth

Is bamboo invasive? Technically, in many parts of the U.S., certain running species are classified as such. But "invasive" is often a stand-in for "unmanaged."

👉 See also: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

If you plant a Mint plant in the ground, it will take over your garden. We don't call it an ecological disaster; we call it a mistake. Bamboo is the same. The different types of bamboo have different "aggressiveness" levels. Phyllostachys bissetii is a monster that will cover an acre before you can blink. Chusquea culeou, a solid-caned clumper from South America, will sit in its corner and mind its business for thirty years.

The responsibility lies with the planter. If you choose a runner, you must use a barrier. If you choose a clumper, you must ensure it’s hardy for your zone.

Real-World Applications and Sustainability

Beyond the backyard, the different types of bamboo are literally changing the construction industry. We are seeing a shift from traditional timber to engineered bamboo.

Why? Because a pine tree takes 25 years to reach maturity. Moso bamboo takes five.

Research from organizations like INBAR (International Network for Bamboo and Rattan) shows that bamboo can sequester significantly more carbon than many tree species. It’s not just a plant; it’s a carbon sink. When you buy bamboo flooring or clothing, you’re usually dealing with Phyllostachys edulis. However, be careful with "bamboo fabric." Most of it is just rayon made from bamboo cellulose through a heavy chemical process. It’s not as "green" as the marketing suggests.

If you want true sustainability, use the raw poles. Build a trellis. Make a fence. That’s where the material shines.

How to Actually Choose Your Bamboo

Don't buy based on a picture on a website. Follow these steps instead:

- Check your USDA Hardiness Zone. If you’re in Zone 5, your options are limited to specific Fargesia species. If you’re in Zone 9, the world is your oyster.

- Measure your footprint. Do you have a 3-foot wide strip or a 20-foot wide field? If it’s a narrow strip, you need a clumper or a very well-contained runner.

- Identify the goal. Privacy? Look at Bambusa multiplex (Hedge Bamboo). It’s dense and leafy from top to bottom. Timber? Look at Phyllostachys vivax.

- Source from a specialist. Big box stores often mislabel bamboo or just call it "Green Bamboo." Go to a nursery that specializes in bamboo. They will know the difference between a Bambusa and a Phyllostachys.

Actionable Steps for Success

If you're ready to pull the trigger and add some of these plants to your landscape, start with a plan that accounts for the long game.

- Kill the "Plant and Forget" Mentality: Before planting, dig your trench for the root barrier if you've chosen a runner. Use 60-mil or 80-mil HDPE barrier. Leave about 2 inches of the barrier above ground so you can see if a rhizome tries to "hop" over the top.

- Test Your Soil: Bamboo likes slightly acidic soil (pH 6.0 to 6.5) with plenty of organic matter. If you have heavy clay, you'll need to amend it or the roots will rot in the standing water.

- Install Irrigation: Drip lines are perfect for bamboo. It likes consistent moisture, not a flood-and-drought cycle.

- Check Local Ordinances: Some cities have banned the planting of running bamboo. Always check your local laws before putting a Phyllostachys in the ground, or you might face heavy fines and the cost of professional removal, which can run into the thousands.

- Focus on the "Leap" Year: Remember the old gardening adage for bamboo: The first year it sleeps, the second year it creeps, and the third year it leaps. Don't be disappointed if your new plant doesn't explode in size immediately. It's building a root system. By year three, you'll be glad you planned for its full size.