You’re standing in a nursery, and you see a tag that says Pelargonium. Most people just say "Geranium." But here’s the kicker: they aren't the same thing. Not really. We’ve been mixing up different names of flowers for centuries, and honestly, it’s mostly because Latin is hard and common names are, well, common.

Naming a plant is weird. It’s part science, part folklore, and part accidental history. You have the "official" binomial nomenclature—that’s the genus and species—and then you have the nicknames that vary from one zip code to the next.

The Confusion Between Common and Botanical Labels

Carl Linnaeus is the guy we usually blame for the complicated stuff. Back in the 1700s, he decided every living thing needed a two-part name. It’s precise. If you go to a florist in Tokyo or a botanical garden in London and ask for Lavandula angustifolia, everyone knows you want English Lavender. But if you just say "lavender," you might end up with French lavender, which smells totally different and doesn't handle frost well.

Common names are messy. Take the "Bleeding Heart." It’s poetic, right? It looks like a little heart dripping a drop of blood. In a lab, it’s Lamprocapnos spectabilis. Most gardeners will tell you the common name is way better because it actually describes the flower's soul. But common names can also be dangerous. "Monkshood" sounds cool, but its other name is "Wolfsbane." It’s incredibly toxic. If you don’t know the scientific name (Aconitum), you might underestimate just how careful you need to be.

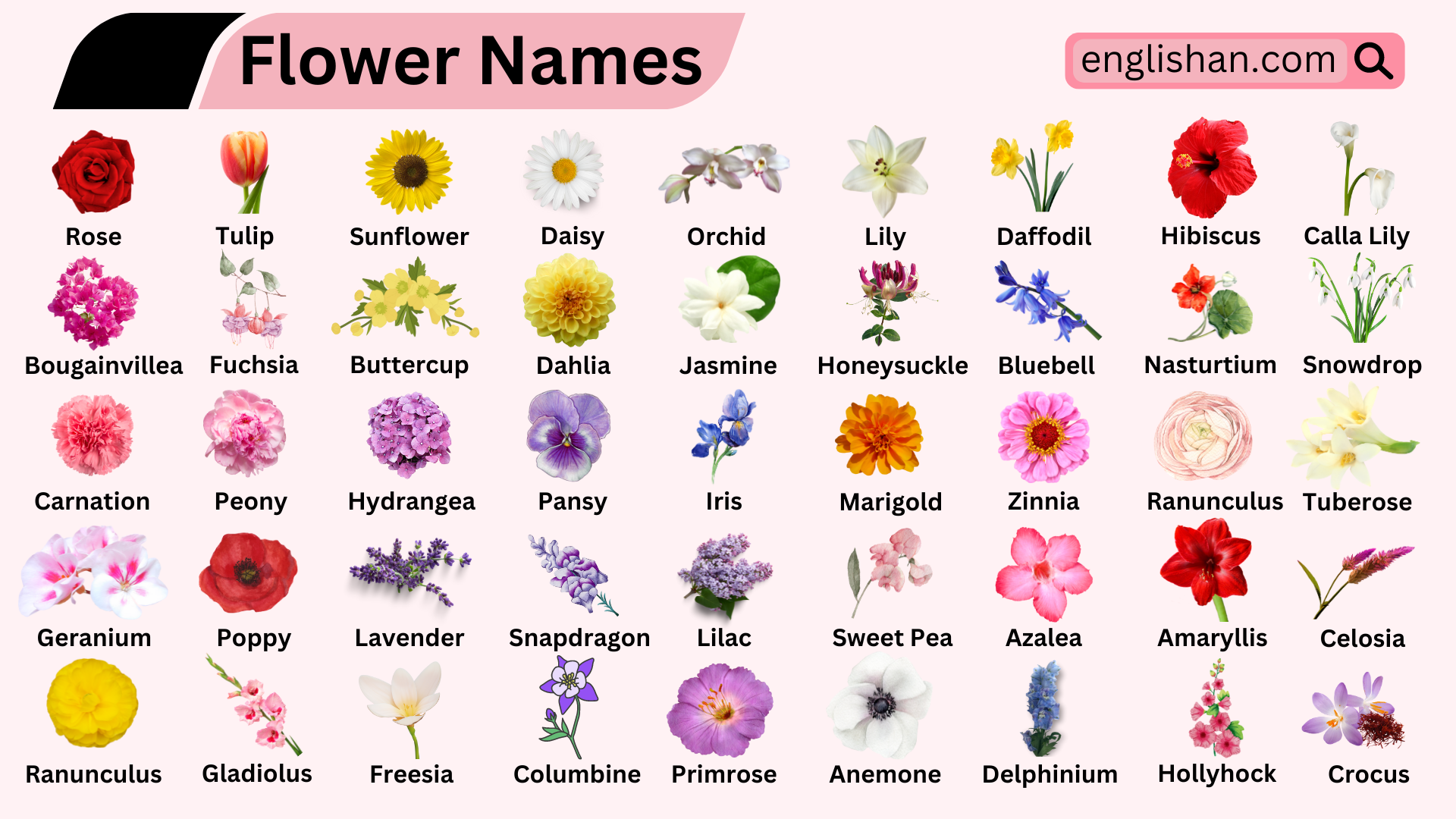

People get the different names of flowers mixed up all the time because of how they look. We call things "lilies" that aren't lilies at all. Daylilies? Not true lilies. Calla lilies? Nope. Water lilies? Not even close. A "true" lily must belong to the genus Lilium. Everything else is just an impostor using a famous brand name to get attention.

Why Regional Names Are Basically a Secret Language

Depending on where you grew up, a flower might have five different identities. In the American South, you might hear people talk about "Lenten Roses." They aren't roses. They are Hellebores. They bloom in late winter or early spring, often around Lent. It’s a functional name. It tells you when it shows up.

🔗 Read more: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Then you have the "Forget-Me-Not." The name is almost universal across Europe, rooted in a German legend about a knight who fell into a river while picking flowers for his lady. As he drowned, he tossed the bouquet and yelled, "Forget me not!" It’s a great story. Scientifically? It’s Myosotis.

Sometimes the name reflects how we use them. "Calendula" is often called "Pot Marigold." Why? Because people used to throw the petals into a cooking pot to color cheese or flavor stews. It’s a practical, blue-collar name for a flower that works for its living.

The Hidden History in Latin Roots

If you look at the different names of flowers through a linguistic lens, you start seeing patterns. Latin isn't just there to be annoying; it’s a physical description.

- Helianthus: Helios (sun) and anthos (flower). Literally, Sunflower.

- Chrysanthemum: Chrysos (gold) and anthemon (flower).

- Digitalis: From digitus, meaning finger. Because you can stick your finger inside the Foxglove bell.

It’s almost like a code. If you see the word officinalis in a flower’s name—like Rosmarinus officinalis—it means that plant was historically kept in an "officina," or a monastery's storeroom for medicines. It tells you that for hundreds of years, humans used that specific flower to heal something.

When Names Get Lost in Translation

We also have "cultivars." This is where things get really specific. You might have a Rose (the genus Rosa), but the name on the tag is "Peace" or "Double Delight." These are trademarked names. They’re like brand names for sneakers.

💡 You might also like: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

There’s a famous case with the "Poinsettia." We call it that because of Joel Roberts Poinsett, the first U.S. Minister to Mexico, who brought the plant north in the 1820s. In Mexico, its name is Flor de Nochebuena (Christmas Eve Flower). Its botanical name is Euphorbia pulcherrima, which translates to "the most beautiful Euphorbia." Three names, one plant, and a whole lot of cultural history packed into those red bracts.

And let’s talk about the "Dandelion." We think of it as a weed, but the name is actually a corruption of the French dent-de-lion, or "lion’s tooth." Look at the leaves. They’re jagged. They look like teeth. If we called it Taraxacum officinale at a backyard BBQ, people would think we were crazy, but calling it a lion's tooth makes it sound almost majestic.

Moving Beyond the Basics

If you want to actually master different names of flowers, you have to stop looking at them as just "pretty things" and start looking at their lineage.

Don't just buy a "Daisy." Ask if it’s a Shasta Daisy (Leucanthemum x superbum) or an English Daisy (Bellis perennis). One grows three feet tall and likes the sun; the other hugs the ground and pops up in your lawn. Using the wrong name leads to the wrong planting location, which usually leads to a dead plant.

The biggest mistake is assuming a common name is enough. It isn't. Not if you’re serious about gardening or even just buying a bouquet that won't wilt in two days. You need to know the "Latin plus Common" combo. It’s the only way to be sure what you’re actually holding.

📖 Related: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

Actionable Steps for Learning Flower Names

If you want to get better at identifying and naming plants without feeling overwhelmed, start here.

Grab a field guide that lists both names. Don't rely on apps that only give you one result. Look for books by the Royal Horticultural Society or similar local authorities. They emphasize the relationship between the common name and the botanical one.

Check the tags at the nursery. Most people toss them. Don't. Keep them in a drawer or take a photo. Note the genus. Once you know the genus, you start to see similarities between plants you never realized were related, like how a tomato flower looks a bit like a nightshade because, well, they are.

Learn the "Descriptor" Latin. Words like alba (white), rubra (red), or nanus (dwarf) appear in thousands of plant names. Once you know those five or ten words, you can look at a label and know exactly what the plant will look like before it even blooms.

Focus on one family at a time. Start with the Asteraceae family (daisies, sunflowers, zinnias). They all have that "composite" flower head. Once you recognize the family traits, the specific names become much easier to categorize in your head.

Don't be afraid to sound pretentious. If you call it a Hellebore instead of a Winter Rose, you aren't being a snob. You're being accurate. Accuracy keeps you from planting a "sun-loving" rose in a spot that only supports a shade-loving Hellebore. It’s about the health of the plant, not just the labels.