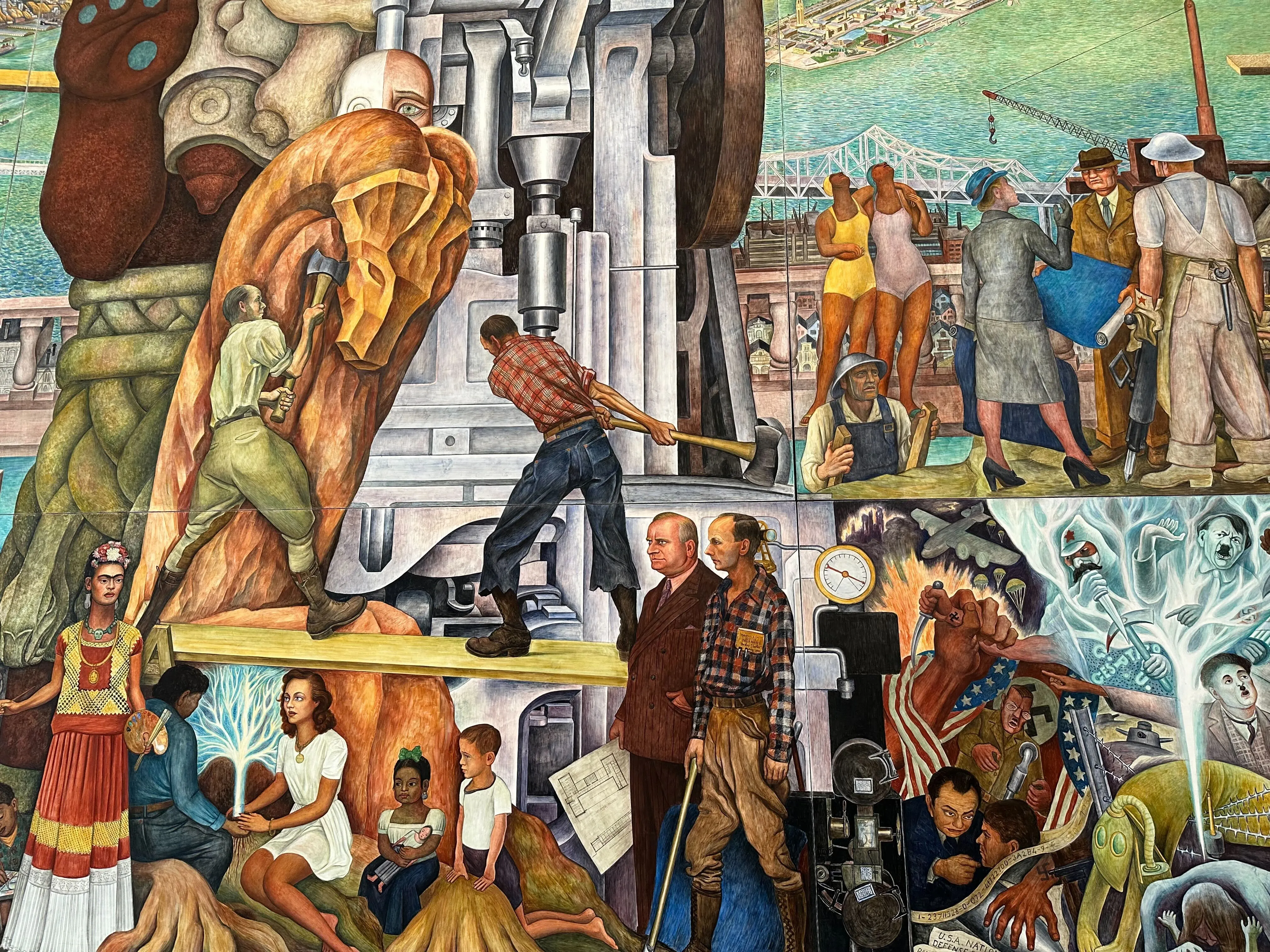

You’ve probably seen the photos. A massive, towering wall covered in workers, gears, and vibrant, earthy colors that feel like they’re vibrating. That’s the classic Diego Rivera look. But there is a lot more to Diego Rivera art pieces than just "big paintings of factories."

Honestly, the guy was a walking contradiction. He was a devout Communist who took massive paychecks from the world's richest capitalists, like the Rockefellers and the Fords. He painted the "common man" but lived a life of high-society drama and international fame.

If you look closely at his work today, you realize he wasn't just decorating buildings. He was basically live-tweeting the 20th century in wet plaster.

The "Detroit Industry" Murals: A Love Letter to Gears

Back in 1932, Edsel Ford—yes, Henry Ford’s son—invited Rivera to Detroit. The city was hurting. The Great Depression was hitting hard. Rivera spent months at the Ford River Rouge plant, just watching. He was obsessed with the way the machines looked.

He didn't see them as cold metal. To him, they were like modern-day Aztec deities.

The result? The Detroit Industry Murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). It’s a 27-panel masterpiece. In the center, you see the assembly of the 1932 Ford V-8 engine. It looks like a giant, pulsing heart.

But here’s what most people miss: Rivera didn't just paint the "cool" parts of the factory. He painted the vaccination of a child in one corner, which local clergy at the time called "sacrilegious." They thought it looked too much like a twisted Nativity scene. There was a huge outcry to have the murals whitewashed and destroyed.

👉 See also: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Luckily, Edsel Ford stood his ground. He basically told the critics that he liked the art and it was staying. Today, it’s a National Historic Landmark. It’s weird to think that one of the most "American" pieces of art in the country was painted by a Mexican Marxist who was technically trying to critique the very system paying his bills.

The Rockefeller Scandal: What Really Happened

If you want to talk about Diego Rivera art pieces and drama, you have to talk about Man at the Crossroads. This is the one that got destroyed.

In 1933, the Rockefellers hired Rivera to paint a mural for the RCA Building in New York. The theme was supposed to be about man looking toward a better future. Rivera, being Rivera, decided that a "better future" definitely included Vladimir Lenin.

He painted a portrait of Lenin holding hands with workers.

Nelson Rockefeller saw it and, understandably, freaked out a bit. He asked Rivera to remove Lenin and maybe put an anonymous face there instead. Rivera refused. He said he’d rather the whole thing be destroyed than change his vision.

The Rockefellers took him literally.

✨ Don't miss: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

They covered the mural with canvas, paid Rivera his full fee ($21,000, which was a fortune back then), and then a few months later, workers came in with axes and smashed it to bits. Rivera was furious. He later recreated the whole thing in Mexico City at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, retitling it Man, Controller of the Universe.

He even added a little "revenge" detail in the new version: a portrait of John D. Rockefeller Jr. drinking a martini near a depiction of syphilis bacteria.

The Mystery of the "Water, Source of Life" Mural

Not all of his stuff is in giant museums. Some of it is literally underwater—sort of.

The Cárcamo de Dolores in Mexico City's Chapultepec Park is one of his most underrated works. It’s a functional water distribution chamber. Rivera painted a mural called Agua, el Origen de la Vida (Water, the Source of Life) inside the actual tank where the water used to flow.

For years, the mural was submerged. He used a special rubber-based paint he thought would hold up, but the water eventually started to eat away at it.

It’s been restored now, and the water is diverted so you can actually see it. It’s a trippy, psychedelic look at evolution. You see microscopic organisms, fish, and then humans emerging from the muck. It’s quiet, weird, and feels much more personal than his loud, political stuff.

🔗 Read more: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Why You Should Care About These Pieces Now

People tend to think of Rivera as "Frida Kahlo’s husband" these days, which is a bit of an oversimplification. While Frida was looking inward at her own pain, Diego was looking outward at the world.

He wanted his art to be for everyone. That’s why he did frescos. You can’t easily sell a wall. You can’t put a mural in a private vault where no one can see it.

His style—those rounded, heavy figures and the crowded, "horror vacui" compositions—influenced almost every public muralist who came after him. From the WPA artists in the 1930s to modern street artists in Los Angeles and Chicago, his DNA is everywhere.

Actionable Ways to Experience Rivera’s Art

If you actually want to see these things in person, don't just go to a random gallery. You have to go to the buildings themselves.

- The Detroit Institute of Arts: This is the big one in the US. The Rivera Court is the only place in the world where you can stand in a room completely surrounded by his work.

- The National Palace (Mexico City): This is where you find The History of Mexico. It covers a massive staircase. It’s free to enter, but you need to bring a physical ID to get into the government building.

- Palacio de Bellas Artes: Go here to see the "revenge" version of the Rockefeller mural. It’s in the heart of Mexico City and the building itself is an Art Deco masterpiece.

- San Francisco: Check out the Pan American Unity mural. It moved around for a bit but it’s one of his most complex later works, showing the "marriage" of the North and South American spirits.

Rivera’s work isn't just "old art." It’s a reminder that art has always been messy, political, and a little bit dangerous. Whether you love his politics or hate them, you can't deny that when the guy hit a wall with a paintbrush, he made something that lasted.

To get the most out of a visit, try to spot the "hidden" faces. Rivera loved to paint his friends, his enemies, and even himself (usually as a small, frog-like man) into the crowds. It’s like a 20th-century version of Where’s Waldo, but with way more social commentary.