He was bleeding before he even got into the cockpit. Honestly, that’s the most Evel Knievel way to start a world-record attempt. On September 8, 1974, the atmosphere at the Twin Falls, Idaho, jump site wasn't just electric—it was borderline homicidal. Thousands of people had descended on the rim of the canyon, fueled by beer, sun, and the morbid curiosity of seeing a man potentially plummet 500 feet to his death. People often ask, did Evel Knievel jump the Snake River, and while the short answer is technically "yes," the actual execution was a magnificent, terrifying failure that almost drowned the world’s most famous daredevil in a cockpit full of river water.

It wasn't a motorcycle. You've probably seen the toys or the posters of Evel on his Harley-Davidson XR-750, but a bike wouldn't work here. The gap was nearly a mile wide. To clear that kind of distance, Knievel needed a rocket. Specifically, the Skycycle X-2.

The Steam-Powered Pipe Dream

The physics of the jump were handled by Doug Malewicki and Robert Truax. Truax was a legitimate rocket scientist who had worked for the Navy and NASA, which gave the project a veneer of scientific credibility it probably didn't deserve given the budget and the stakes. They didn't use conventional rocket fuel. Instead, the Skycycle was essentially a giant pressure cooker on wheels. It used superheated water that, when released through a nozzle, flashed into steam and provided thousands of pounds of thrust.

Knievel wasn't a scientist. He was a showman from Butte, Montana, who understood one thing: people pay to see the crash.

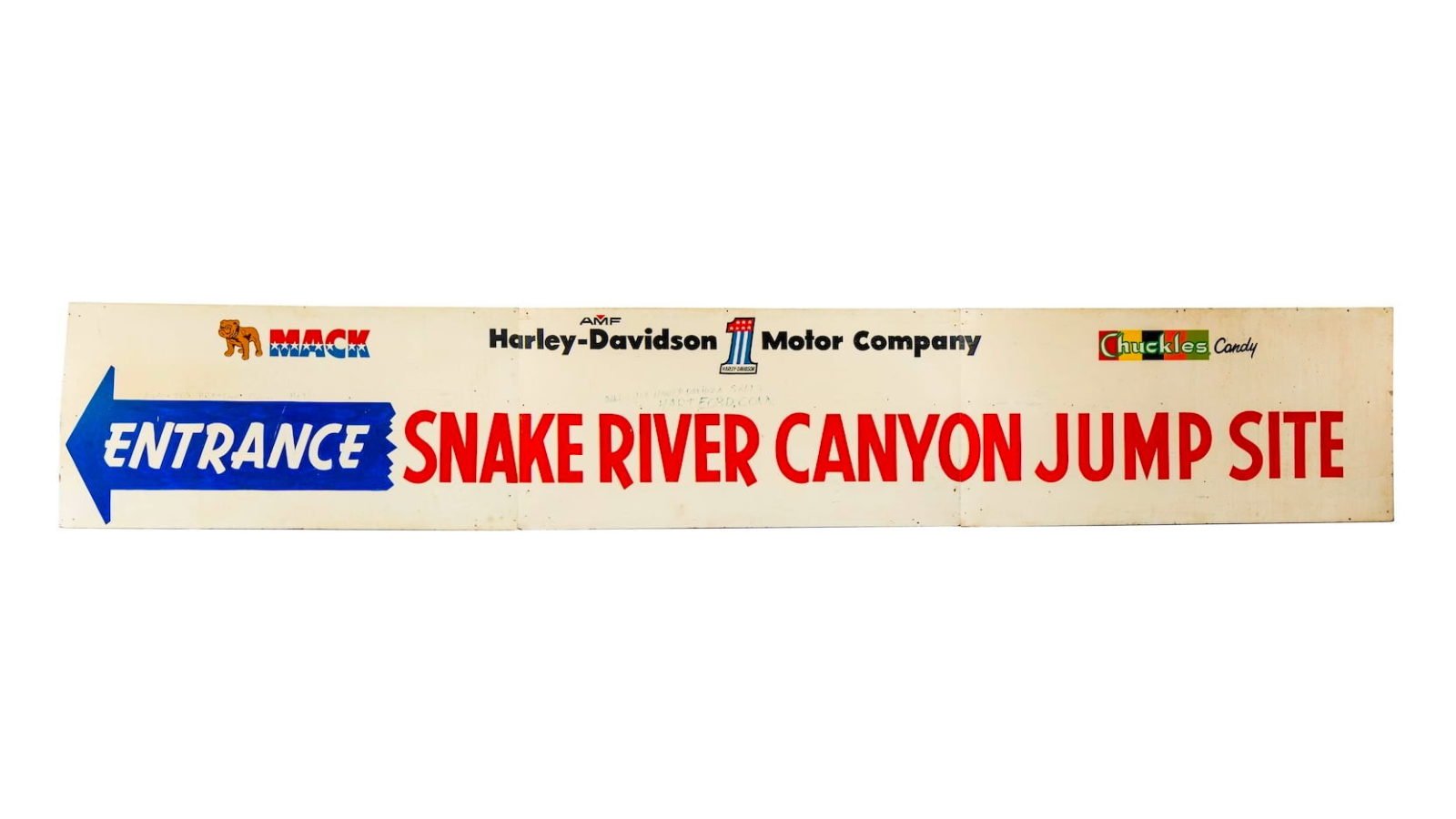

The build-up to the event was a media circus that makes modern influencers look like amateurs. Knievel had sold the rights to ABC's Wide World of Sports, but the live feed was actually handled through Top Rank, shown in theaters via closed-circuit television. It was the precursor to the modern Pay-Per-View model. Tension was so high at the site that the "canyon rats" (the rowdy spectators) started rioting, overturning beer trucks and harassing the security guards.

Then came the moment of truth.

What Actually Happened Over the Canyon

When the countdown hit zero, the Skycycle X-2 blasted off the ramp with a deafening roar. For about two seconds, it looked like it might actually work. The rocket surged up the massive steel ramp, screaming toward the opposite rim.

But then, disaster.

The drogue parachute—the small chute meant to stabilize the craft before the main one deployed—deployed prematurely. It popped out while the rocket was still under full thrust. Imagine trying to win a drag race while someone throws an anchor out your window. The drag from the parachute immediately fought against the steam engine, causing the Skycycle to lose its forward momentum and begin a slow, agonizing tumble into the canyon.

📖 Related: How to watch vikings game online free without the usual headache

The wind caught the chute. Instead of soaring across to the other side, Evel was blown backward, drifting toward the very wall he had just launched from.

He didn't make it to the other side. Not even close. The Skycycle crashed into the rocky talus at the bottom of the canyon, just feet from the water's edge. If he had landed in the river, the heavy straps holding him into the cockpit would have likely pinned him underwater, and he would have drowned inside his own rocket.

Why the Failure Didn't Kill the Legend

Technically, if you're looking for a successful transit from Point A to Point B, the answer to did Evel Knievel jump the Snake River is a resounding no. He failed to reach the north rim. He landed at the bottom.

However, in the world of 1970s sports entertainment, the "jump" was the event itself. Knievel walked away with a few scrapes and a massive payday—reportedly around $6 million. He had survived. To the public, the fact that he strapped himself into a steam-powered tin can and fired himself into a canyon was enough to cement his status as a folk hero.

The Engineering Flaw

Years later, the debate still rages among enthusiasts. Was the parachute deployment a mechanical failure, or did Evel pull the lever himself?

Some crew members, including those who worked closely on the X-2, suggested that Knievel might have panicked and pulled the chute early. Knievel always denied this, blaming a faulty bolt or a design flaw in the release mechanism. If you look at the footage—and there is plenty of it—the chute definitely deploys while the steam is still venting at high pressure. It was a chaotic mess of physics and bad luck.

The canyon itself is a brutal environment. The thermals and wind gusts inside the Snake River Gorge are unpredictable. Even if the chute hadn't deployed, the aerodynamics of the Skycycle were questionable at best. It was essentially a lawn dart with a seatbelt.

The 2016 Success That Proved It Was Possible

For decades, the Snake River jump remained an "unfinished" piece of American history. It sat there, a taunting gap in the Idaho landscape. It wasn't until 2016 that professional stuntman Eddie Braun decided to finish what Knievel started.

👉 See also: Liechtenstein National Football Team: Why Their Struggles are Different Than You Think

Braun didn't try to reinvent the wheel. He built a "Spirit of Evel" rocket that was nearly identical to the original X-2, using the same steam-powered technology. He even hired Scott Truax, the son of the original designer, to build it.

On September 16, 2016, Braun strapped in. He launched. The chute stayed tucked until it was supposed to. Braun soared across the canyon, clearing the gap effortlessly and landing safely on the other side.

This success actually adds a layer of nuance to Evel's story. It proved that the rocket worked. The design was sound. The failure in 1974 wasn't a failure of imagination or engineering—it was a failure of execution.

Impact on Idaho and the Stunt World

Twin Falls is still defined by that day in 1974. If you visit today, you can still see the massive dirt ramp structure sitting on the edge of the canyon. It’s a weirdly haunting monument to human ego.

The event changed how stunts were televised. It showed that the "build-up" was just as valuable as the "pay-off." It also highlighted the absolute lack of regulation in the early days of extreme sports. There were no safety commissions or standardized protocols. It was just a guy, a rocket, and a prayer.

Breaking Down the Numbers

- Distance attempted: Approximately 1,600 feet.

- Top speed reached: Around 350 mph before the chute popped.

- Altitude: The ramp was roughly 500 feet above the river floor.

- The "Payday": Knievel walked away with roughly $6 million, which is about $35 million in today's money.

What Most People Get Wrong

The biggest misconception is that he fell into the water. Most people picture him splashing down like a failed cannonball. In reality, the wind saved him. By blowing the chute back toward the south rim, the wind kept him on the rocks.

Another common myth is that he used a jet engine. People hear "rocket" and think of a fighter jet. But the X-2 was strictly steam. No combustion. No fire. Just 500-degree water being forced through a hole.

How to Experience the History Yourself

If you're a fan of American history or extreme sports, the Snake River Canyon is a pilgrimage site.

✨ Don't miss: Cómo entender la tabla de Copa Oro y por qué los puntos no siempre cuentan la historia completa

1. Visit the Launch Site

The original dirt mound is located on private property but is clearly visible from the Snake River Canyon Rim Trail in Twin Falls. It’s a surreal experience to stand where the ramp once stood and look across that massive gap. You realize how insane you’d have to be to try it.

2. Check out the Museums

The Evel Knievel Museum in Topeka, Kansas, is world-class. They have the "Skycycle X-2" (a backup/prototype) and the "Big Red" Mack truck he used to haul his gear. They even have a VR experience that simulates the jump.

3. The Perrine Bridge

While you're in Twin Falls, you'll see the Perrine Bridge. It's one of the few places in the U.S. where BASE jumping is legal year-round without a permit. It’s the modern spiritual successor to Evel’s madness.

Moving Forward: The Legacy of the Leap

Evel Knievel didn't "clear" the Snake River, but he conquered the public imagination. He taught a generation that failing spectacularly is sometimes better than succeeding quietly.

If you're looking for actionable insights from the 1974 disaster, look at the importance of redundant systems. In modern engineering, we use "fail-safes." Knievel had a "fail-deadly" setup. One bolt goes, the chute pops, the jump ends.

To really understand the event, you have to look past the result. You have to look at the courage it took to sit in that seat. He knew the parachute was a risk. He knew the steam was volatile. He did it anyway because he had promised the world he would.

Whether he made it to the other side or not is almost irrelevant. The fact that we are still talking about a three-minute event from 50 years ago tells you everything you need to know about who won that day.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Watch the original 1974 footage with a focus on the parachute deployment; you can clearly see the "tug" that ruins the trajectory.

- Compare it to Eddie Braun’s 2016 "Spirit of Evel" jump to see how the physics should have looked.

- Research Robert Truax’s other projects—he was a pioneer of low-cost space flight long before SpaceX was a thought.