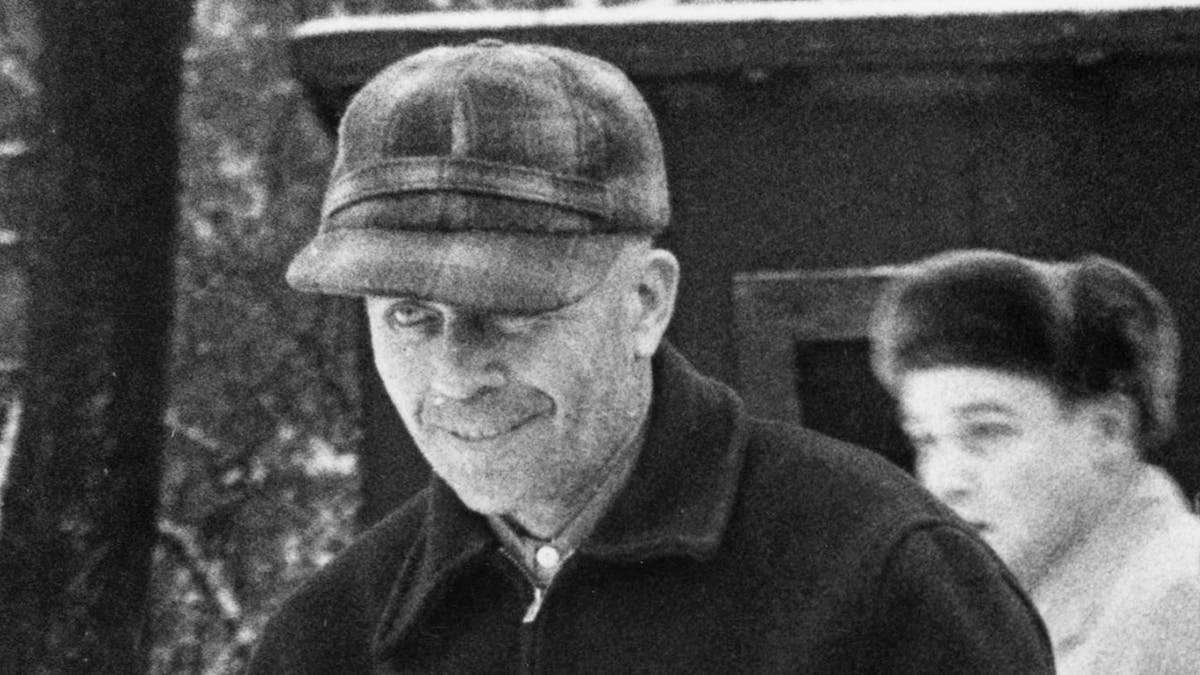

People love a good scare, and honestly, the legend of Ed Gein provides enough nightmare fuel to last several lifetimes. He’s the guy who inspired Psycho, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and The Silence of the Lambs. But when you start digging into the actual police reports from 1957, the lines between Hollywood horror and Wisconsin reality get messy. One question pops up constantly in true crime forums: did Ed Gein kill the nurse in real life, or is that just a bit of movie magic that stuck to his name over the decades?

The short answer is no. But the long answer is way more complicated because of who Gein actually was—and who he wasn't.

Most people associate Gein with a massive body count because his house was essentially a museum of the macabre. When Sheriff Art Schley and his men entered that farmhouse in Plainfield, they found things that defied human logic. We’re talking about chairs upholstered in skin and a box full of noses. Naturally, the public assumed he was a serial killer on the level of Ted Bundy or Jeffrey Dahmer. In reality, Gein was primarily a grave robber. He was a "ghoul" in the most literal, old-school sense of the word.

The Confusion Surrounding the Nurse

So, where does this "nurse" story come from? If you’ve seen Texas Chain Saw Massacre or any slasher flick from the 70s, you know the trope. There’s often a medical professional or a caregiver who meets a grisly end. Specifically, in the 1974 film Deranged—which is a very thinly veiled, almost beat-for-beat retelling of the Gein story—the protagonist kills a nurse. Because that movie was marketed as being based on a true story, a lot of people walked away thinking Gein actually hunted down a medical worker in Plainfield.

He didn't.

Gein’s confirmed victim list is surprisingly short, though no less horrific. There are only two names that everyone agrees on: Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden. Mary Hogan ran a local tavern. She went missing in 1954. When police finally searched Gein’s property three years later, they found her head in a paper bag. Bernice Worden was the owner of the local hardware store. Her disappearance is what actually led the police to Gein’s door in the first place. Her son, Frank Worden, was a deputy who noticed the last entry in the store's sales book was for a gallon of antifreeze, and he knew Gein had been talking about buying some.

The Victims We Know About

To understand why the "nurse" theory persists, you have to look at the atmosphere in 1950s Wisconsin. It was a time of deep repression and small-town secrets. When the news broke about what Gein was doing in that house, the entire state went into a collective panic. Every missing person case within a 50-mile radius was suddenly Gein’s fault.

📖 Related: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

Bernice Worden's death was the catalyst. Gein killed her on November 16, 1957. When the police arrived at his "House of Horrors," they found her body dressed out like a deer in the summer kitchen. It was a scene so visceral that Sheriff Schley ended up with physical and psychological trauma that many say led to his early death.

But the nurse? She just doesn't exist in the court records.

There were rumors about a missing girl from a nearby town, and some speculated Gein was involved in the disappearance of two hunters, but nothing was ever proven. Gein confessed to the murders of Hogan and Worden, but he adamantly denied killing anyone else. He insisted that the rest of the "materials" in his home came from late-night trips to local cemeteries. He even named the graves. He told investigators he would go into a daze, visit the graves of middle-aged women who reminded him of his mother, Augusta, and bring them home.

Why the "Nurse" Myth Still Floats Around

Movies are powerful. They shape our collective memory of historical events more than history books do. When Robert Bloch wrote the novel Psycho, he lived only 35 miles away from Plainfield. He was struck by the idea that a "normal" neighbor could be a monster. But Bloch added layers of fiction to make the story work as a thriller.

Later, when Thomas Harris created Buffalo Bill for The Silence of the Lambs, he pulled from Gein’s habit of making "suits" out of skin. In the fictional world, these killers often targeted people with specific roles—nurses, students, travelers.

If you're asking did Ed Gein kill the nurse in real life, you might be thinking of his brother, Henry. Now, this is where the real-life mystery actually gets interesting. Henry Gein died in 1844 under very suspicious circumstances during a marsh fire near the family farm. He had bruises on his head that didn't match a fire-related death. Ed was the one who led the police to the body. At the time, the coroner ruled it heart failure, but modern criminal profilers almost universally believe Ed killed Henry because Henry had been critical of Ed’s obsessive relationship with their mother.

👉 See also: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

But Henry wasn't a nurse. He was a laborer.

The Reality of the Plainfield Investigation

Let’s look at the facts of the 1957 search. The investigators found:

- A wastebasket made of human skin.

- Human skin covering several chair seats.

- Skulls on his bedposts.

- A belt made from female nipples.

- A lampshade made from the skin of a human face.

It’s easy to see why people assume he was a prolific serial killer. How could one man get all that "material" from just two murders? The answer, as disgusting as it is, was the graveyards. Gein was a skilled handyman. He knew the layout of the town. He knew who died and when. He admitted to opening at least nine graves. Authorities actually exhumed some of those graves to see if he was telling the truth. In many cases, the coffins were indeed empty or tampered with.

Honestly, the truth is almost weirder than the fiction. Gein wasn't a hunter. He wasn't a "stalker" in the way we think of modern serial killers. He was a broken, schizophrenic man who was trying to literally crawl back into his mother's skin.

Distinguishing Fact from Film

If you want to be a true crime stickler, you have to separate the "Plainfield Ghoul" from the "Leatherface" characters.

- Ed Gein: Confirmed 2 murders. Total bodies involved in the house: parts from roughly 15-20 individuals (mostly from graves).

- The Movie Counterparts: Often kill dozens, including nurses, teenagers, and police officers.

There is no record in the Wisconsin Department of Justice archives or the local Waushara County files that mentions a nurse as a victim. No missing persons reports for nurses in that area align with Gein's timeline of activity.

✨ Don't miss: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

The idea of Gein killing a nurse likely stems from a conflation of his "caregiver" persona. In his later years, after being found "not guilty by reason of insanity," Gein was sent to the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. He was actually described as a model patient. He was gentle, soft-spoken, and helpful to the—you guessed it—nursing staff. He spent decades around nurses before dying of cancer and respiratory failure in 1984.

It’s a bit of a dark irony. The man who mutilated bodies was apparently a "perfect gentleman" to the nurses who cared for him in his old age.

What This Tells Us About True Crime

We have a tendency to want our villains to be "bigger" than they are. We want them to have these elaborate backstories and high body counts because it makes the evil feel more significant. But Ed Gein was a lonely, isolated man living in filth. He was a product of a bizarre, abusive upbringing and a complete break from reality.

When you ask did Ed Gein kill the nurse in real life, you're really asking about the boundaries of his madness. His madness was focused. It was centered on his mother, Augusta. He wasn't out to kill the world; he was trying to recreate a person he lost. That doesn't make him any less of a monster, but it does make him a different kind of monster than the ones we see on the big screen.

How to Verify True Crime Facts

If you’re diving into the Gein case or any other historical crime, here’s how to avoid getting tricked by "movie facts":

- Check the Primary Sources: Look for the actual trial transcripts or the initial police reports from 1957.

- Verify the Victim List: Stick to names confirmed by the coroner. In Gein's case, it's Worden and Hogan.

- Identify the "Based On" Influence: Recognize that "inspired by a true story" usually means 90% fiction and 10% name-dropping.

- Look at Local Archives: Small-town newspapers from the era (like the Stevens Point Journal) are gold mines for what was actually happening on the ground versus what the national media sensationalized later.

Gein’s story is grim enough without adding fictional nurses to the mix. The reality of a man sitting in a dark farmhouse surrounded by the remains of the local deceased is plenty terrifying on its own.

For those looking to understand the full scope of the case, the best next step is to look into the psychological evaluations performed by Dr. Schubert during Gein's initial incarceration. They provide a chilling look into the mind of a man who didn't see himself as a killer, but as a hobbyist of the dead. You might also want to research the "Plainfield Ghoul" era of Wisconsin folklore to see how the community processed the trauma of Gein's discovery through dark humor and urban legends.