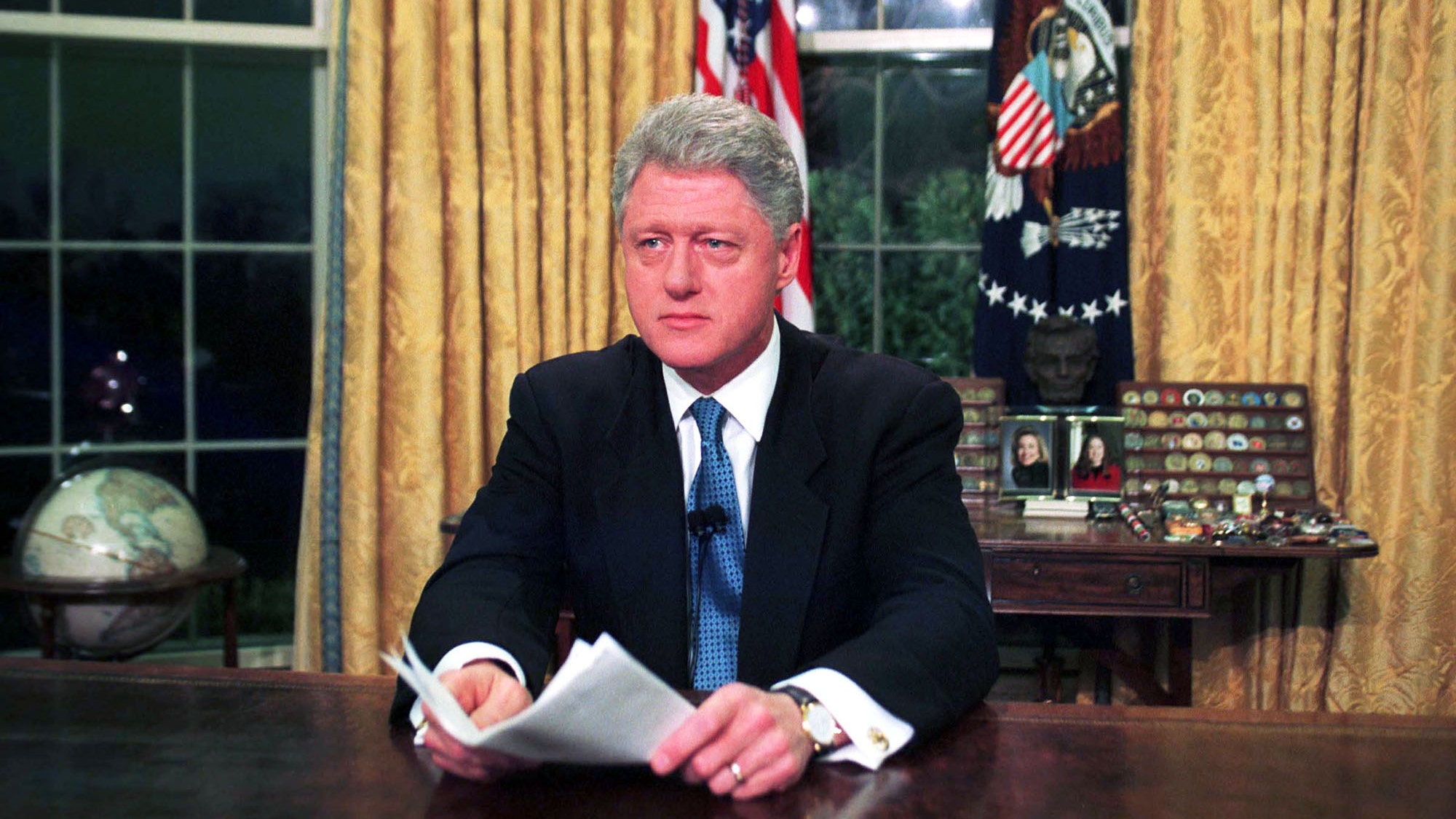

You’ve probably heard the soundbite. It’s a classic of 1990s political lore. Standing before Congress in 1996, Bill Clinton leaned into the microphone and declared, "The era of big government is over." It was a shocking thing to hear from a Democrat. But was it just talk? When you look at the raw data, the answer is actually a resounding yes. Bill Clinton did reduce the federal workforce, and he did it on a scale that hasn't been seen since.

By the time he left office in 2001, the federal civilian workforce had shrunk by roughly 426,000 employees.

That’s not a rounding error. It was a massive, systematic pruning of the executive branch. To put it in perspective, the federal government under Clinton became the smallest it had been since the Eisenhower administration. Honestly, if a politician tried to pull that off today, the headlines would be inescapable. But back then, it was part of a specific mission led by Vice President Al Gore called "Reinventing Government."

The "Reinventing Government" Initiative

It wasn't just about firing people. That’s a common misconception. Most of the reduction came from a project officially known as the National Performance Review (NPR). Launched in March 1993, this wasn't some dusty academic study. Gore was tasked with making the government "work better and cost less."

The administration didn't want a "meat-axe" approach. Instead, they focused on "streamlining." They looked at the ratios of managers to workers and realized the middle was bloated. In some agencies, there was a manager for every seven employees. Clinton wanted to double that span of control. They also targeted "red tape" functions—the people whose entire jobs were to check the work of other people.

Specifically, they went after:

👉 See also: Otay Ranch Fire Update: What Really Happened with the Border 2 Fire

- Personnel specialists (HR)

- Budget analysts

- Procurement officers

- Accountants and auditors

By 1999, the administration had cut 78,000 management positions alone. They closed nearly 2,000 field offices. They even killed off the Tea-Tasters Board—yes, that was a real thing—and the Bureau of Mines.

Where the Cuts Actually Happened

If you dig into the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data from the 1990s, you see a very specific pattern. While almost every department saw some shrinkage, the Department of Defense (DoD) took the biggest hit.

The Cold War had ended. The "Peace Dividend" was ripe for the picking. Out of those 426,000 lost jobs, over 300,000 were civilian positions within the DoD. It’s easy to say, "Well, they just cut the military," but that's a bit of a simplification. Even without the Defense cuts, non-defense agencies still saw a reduction of more than 100,000 workers.

For instance, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) saw its staff plummet by nearly 45% as it privatized training and investigation functions. The General Services Administration (GSA) cut its staff by about 23% by streamlining how the government buys supplies and manages real estate.

One notable exception? The Department of Justice. It actually grew. This was the era of the 1994 Crime Bill, and the administration was busy hiring thousands of new law enforcement officers and border patrol agents.

✨ Don't miss: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

How They Did It (Without Massive Layoffs)

You’d think cutting 400,000 jobs would lead to a revolution in the streets of D.C. It didn't.

Clinton and Gore were savvy. They didn't rely on mass pink slips, which would have been a political nightmare. Instead, they used the Federal Workforce Restructuring Act of 1994. This law gave agencies the authority to offer "buyouts"—cash incentives of up to $25,000 for employees to resign or retire early.

It worked. Most people took the money and ran. Between buyouts and natural attrition (people retiring and not being replaced), the "involuntary separations" or actual layoffs were kept surprisingly low. Out of the first 240,000 people to leave, only about 20,000 were actually fired or laid off.

The Criticism: Did It Actually Shrink?

Here is where the nuance kicks in. Critics, like those from the Volcker Alliance or the Brookings Institution, often argue that the "reduction" was a bit of a shell game.

They point to outsourcing.

🔗 Read more: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

While the number of "civilian federal employees" went down, the number of federal contractors went up. Basically, the government stopped paying a guy a salary and benefits directly and started paying a private company to provide that same guy. Paul Light, a professor at NYU and a leading expert on the "true size of government," has argued that the "hidden workforce" of contractors and grantees actually grew, meaning the government didn't necessarily get smaller; it just changed its tax form.

There was also the "hollowing out" effect. By losing so many middle managers and junior-level staff, some agencies lost their institutional memory. The share of federal workers under age 35 dropped from 26% to 17% during the Clinton years. The government was getting older and, in some cases, less tech-savvy right as the internet revolution was hitting.

Why This Matters Today

Understanding did Bill Clinton reduce the federal workforce is crucial for anyone looking at modern government reform. It proves that significant downsizing is possible within the executive branch, but it also shows the trade-offs.

If you're looking for the "how-to" on government efficiency, here are the actionable takeaways from the Clinton era:

- Focus on Ratios: Don't just cut randomly. Target the "control" layers—the people who manage the managers.

- Use Buyouts, Not Layoffs: If you want to avoid morale-killing litigation and union fights, voluntary incentives are the most effective tool for headcount reduction.

- Watch the "Shadow Workforce": If you cut internal staff but increase your contract spending, you haven't actually saved the taxpayer money; you've just moved it to a different line item.

- Identify Obsolete Missions: Clinton succeeded because he could point to the end of the Cold War. True workforce reduction usually requires identifying a function that the government simply doesn't need to do anymore.

The Clinton years remain the gold standard for anyone arguing that "the era of big government" can, in fact, be put on a diet. Whether it made the government better is still a debate for the history books, but the numbers don't lie: the workforce definitely got smaller.

To better understand the long-term impact of these changes, you should review the 1999 NPR Status Report or the BLS Monthly Labor Review from December 2000, which provide the final tallies on these historic cuts.