You’re sitting in the doctor's office, and that Velcro cuff starts squeezing your arm until it pulses. The machine beeps. Your nurse mumbles something like "118 over 76" and scribbles it down. You probably know that’s a "good" number, but honestly, if someone asked you to explain the diastolic systolic blood pressure definition right there, could you do it? Most people can’t. They know high is bad and low is... well, also sometimes bad. But the mechanics of what your heart is actually doing during those two distinct phases is where the real story of your health lives.

Blood pressure isn't just a static measurement. It’s a dynamic, living flow.

The Push and the Pause: Defining the Numbers

Think of your heart as a pump. That’s essentially all it is—a very sophisticated, muscular pump. When we talk about the diastolic systolic blood pressure definition, we are looking at the two phases of a single heartbeat.

The top number, systolic, is the pressure in your arteries when your heart beats. It’s the maximum force. When that left ventricle contracts, it slams blood into the aorta. Your arteries have to stretch to accommodate that sudden surge. If those pipes are stiff or clogged, that pressure goes up.

Then there’s the diastolic number, the bottom one. This is the pressure in your arteries when your heart rests between beats. It’s the "quiet" moment. But here’s the thing—it’s never actually zero. Your system is always under some level of tension. If it wasn't, your blood wouldn't keep moving toward your toes and your brain during the breaks.

✨ Don't miss: 2025 Radioactive Shrimp Recall: What Really Happened With Your Frozen Seafood

Why We Care About the Top Number Most (Usually)

For a long time, doctors obsessed over the diastolic number. They thought it was the better predictor of heart attacks. That’s shifted. Now, for people over 50, the systolic pressure is the primary focus. Why? Because as we age, our large arteries get stiff. It’s like a garden hose that’s been sitting in the sun too long; it doesn't give as much.

When your arteries stiffen, the systolic pressure climbs. This is often called "Isolated Systolic Hypertension." You might have a perfectly normal diastolic reading—say, 80—but a systolic reading of 150. That’s a red flag. It means your heart is working overtime just to push blood through a stubborn system.

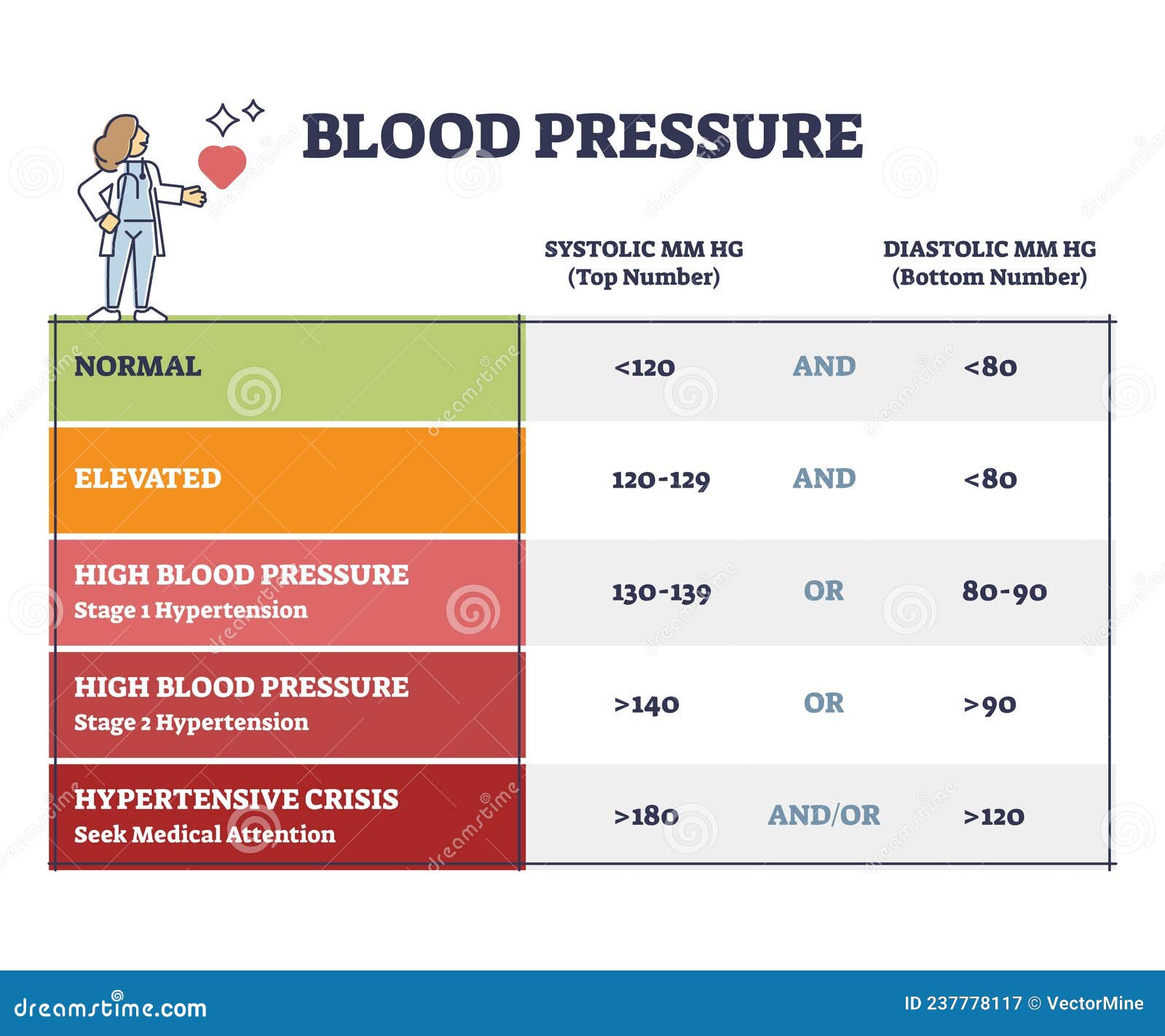

According to the American Heart Association, a normal reading is less than 120/80 mmHg. If you’re consistently hitting 130 systolic, you’ve officially entered Stage 1 Hypertension territory. It’s a sneaky condition. You won't feel it. There’s no "high blood pressure headache" for most people until they are in a crisis. It just quietly wears down the lining of your blood vessels.

The Underestimated Diastolic Pressure

Don't ignore the bottom number though. While systolic gets the headlines, diastolic pressure tells us a lot about the health of your smallest vessels. If your diastolic is high, it means your heart never truly gets a "rest" period. It’s like trying to relax while someone is constantly pushing against your chest.

🔗 Read more: Barras de proteina sin azucar: Lo que las etiquetas no te dicen y cómo elegirlas de verdad

High diastolic pressure is more common in younger adults. If you’re 30 and your pressure is 120/95, that’s a problem. It suggests that your peripheral resistance—the tension in your smaller arteries—is too high. Over years, this "constant squeeze" damages the kidneys and the eyes.

Real-World Factors That Mess With Your Readings

You’ve probably heard of "White Coat Syndrome." It’s real. Some people see a doctor and their systolic spikes 20 points instantly. But there’s also "Masked Hypertension," where your pressure is normal at the office but dangerously high at home while you’re yelling at your kids or stressing over an email.

Specific things change your diastolic systolic blood pressure definition in the moment:

- Caffeine: A double espresso can spike systolic pressure by 5-10 points almost immediately.

- The "Full Bladder" Effect: Believe it or not, having a full bladder can add 10 to 15 points to your reading. Always pee before the cuff goes on.

- Arm Position: If your arm is dangling by your side instead of resting at heart level, the reading will be wrong. Gravity is a factor.

- Talking: If you’re chatting with the nurse while the machine is running, you’re likely adding 5 points to the result.

The New Guidelines and Why They Matter

In 2017, the goalposts moved. The American College of Cardiology lowered the threshold for "high" blood pressure. They didn't do it to sell more meds—they did it because the data showed that damage starts much earlier than we thought.

💡 You might also like: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

If your reading is 125/82, you aren't "fine." You’re "Elevated."

This matters because blood pressure is a leading cause of stroke and heart failure. When the pressure is too high for too long, the heart muscle physically thickens. It gets beefy and stiff, just like any other muscle under a heavy load. But a "beefy" heart is a bad thing. It becomes less efficient at pumping, eventually leading to heart failure.

Taking Action Without Panicking

So, you have the diastolic systolic blood pressure definition down. What now?

First, get a home monitor. One reading at the doctor is a snapshot; a week of readings at home is a movie. You want the movie. Omron and Withings make solid, validated devices. Take your pressure at the same time every morning.

Second, look at your salt intake, but maybe look at your potassium more. Everyone talks about cutting sodium, which is important, but potassium helps your body flush sodium out and relaxes blood vessel walls. Bananas are okay, but spinach, sweet potatoes, and white beans are potassium powerhouses.

Third, move. You don't need to run a marathon. A brisk 20-minute walk drops systolic pressure by making your blood vessels more elastic. It’s literally "stretching" your pipes from the inside out.

Your Immediate Next Steps

- Check your last physical results. Look for the two numbers. If the top is over 130 or the bottom is over 80, it’s time to pay attention.

- Buy an upper-arm blood pressure cuff. Avoid the wrist ones; they are notoriously finicky and often inaccurate depending on how you hold your hand.

- Track for 7 days. Take two readings in the morning and two in the evening. Average them out. This average is your "true" blood pressure, far more accurate than any single check-up.

- Reduce sodium to under 1,500mg for two weeks. See if your numbers budge. Some people are "salt-sensitive," others aren't. This quick test tells you which one you are.

- Schedule a follow-up if your home average is high. Take your log of numbers to your doctor. They will love you for having actual data to work with.