You’ve seen them. Those thin, spindly blue lines tracing patterns under your skin, especially on the back of your hand or the crook of your elbow. Most people think a diagram of the veins in the body is just a boring poster in a doctor’s office, something meant for med students to memorize before a big exam. But honestly, your venous system is a chaotic, brilliant, and deeply personal network that says more about your health than almost any other map. It’s not just a plumbing system. It’s a dynamic pressure-regulation machine.

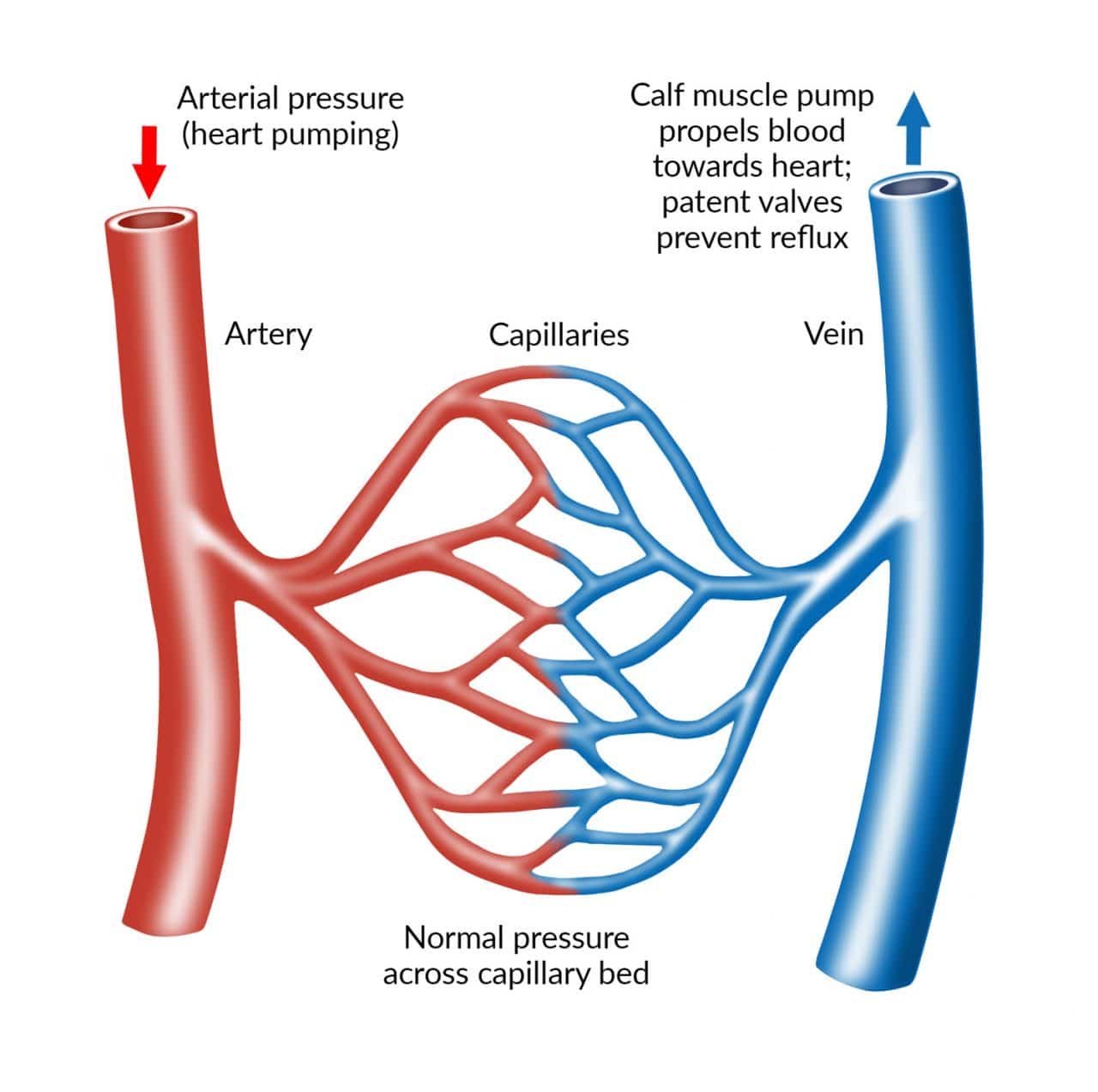

Blood is heavy. Think about that for a second. Your heart pumps it out with a lot of force through the arteries, but once that blood hits the tiny capillaries in your toes, it loses all that momentum. It has to climb back up to your chest against the relentless pull of gravity. That’s where the veins come in. Without a functional map of these vessels, your blood would basically just pool in your ankles until they swelled to the size of watermelons.

Understanding the Map: It’s Not Just One Big Tube

When you look at a professional diagram of the veins in the body, the first thing that hits you is the sheer complexity. It isn’t a straight shot. You’ve got the Deep Venous System, which does the heavy lifting, tucked away near the bones and surrounded by muscle. Then you have the Superficial System—the ones you can actually see—which help regulate your body temperature.

The "bridge" between these two? Perforator veins. They act like one-way shunts.

Let's talk about the big players. The Superior Vena Cava and the Inferior Vena Cava are the literal highways. The Superior handles everything from the chest up. The Inferior takes care of the rest. If you imagine your body as a massive city, these are the 12-lane interstates leading straight into the heart’s right atrium. But the real magic happens in the legs.

The Great Saphenous Vein is a bit of a legend in the medical world. It’s the longest vein in the human body, running from your ankle all the way up to your groin. It’s also the vein surgeons often "harvest" when someone needs a heart bypass. It’s redundant enough that you can live without it, but vital enough that it carries a significant portion of your return blood flow.

The Mystery of the Blue Color

We need to clear something up right now because it drives biology teachers crazy. Your blood is never blue. Not inside your body, not in a vacuum, not ever. It’s dark red when it’s deoxygenated and bright cherry red when it’s fresh from the lungs. The reason a diagram of the veins in the body is almost always colored blue is purely for contrast.

Why do they look blue through your skin? Physics. It’s called the Tyndall effect. Blue light has a shorter wavelength and doesn't penetrate as deeply into your tissue as red light does. The red light gets absorbed by the blood, while the blue light reflects back to your eyes. You’re basically seeing an optical illusion caused by how light bounces off your subcutaneous fat and the vessel walls.

🔗 Read more: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

The Valves: The Unsung Heroes of Venous Return

If you zoom in on a microscopic level of any venous map, you’ll see these tiny, crescent-moon-shaped flaps. These are the valves. Arteries don’t have them because they have the heart’s "pump" pushing things along. Veins are low-pressure. They need these one-way doors to prevent blood from flowing backward.

When you walk, your calf muscles contract. This is often called the "Second Heart." This contraction squeezes the deep veins, forcing blood upward. The valves open to let it pass and then snap shut so it can't fall back down when the muscle relaxes.

- Valvular Insufficiency: This is what happens when those doors get "leaky."

- Varicose Veins: When the blood pools, the vein stretches and twists. It’s literally a topographical change in your body’s map.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): This is the scary one. A clot forms in the deep system, often because of stasis (blood sitting still too long, like on a 15-hour flight to Tokyo).

Dr. Eugene Strandness, a pioneer in vascular surgery at the University of Washington, spent decades mapping how these flow patterns change under stress. His work showed that the venous system isn't static; it's constantly rerouting itself based on your posture and activity level.

Why the "Standard" Diagram Is Usually Wrong

Here is a secret: nobody’s venous map looks exactly like the textbook. Arteries are pretty predictable. They usually go where they are supposed to go. Veins? They are rebels.

Medical illustrators like Frank Netter created the gold standard for what a diagram of the veins in the body should look like, but in a real cadaver lab or an ultrasound suite, things get messy. People have "accessory" veins. Some people have double inferior vena cavas. Others have unique branching patterns in their arms that make them "hard sticks" for nurses trying to start an IV.

If you’ve ever had a phlebologist (a vein specialist) look at your legs with a duplex ultrasound, they aren't looking for a perfect match to a poster. They are looking for your specific "highway" and where the "traffic jams" are occurring.

The Portal System: The Body’s Security Detail

There is one part of the venous map that is totally weird and different: the Hepatic Portal System. Normally, blood goes Heart -> Artery -> Capillary -> Vein -> Heart.

💡 You might also like: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

The Portal System says "Wait a minute."

It takes nutrient-rich (and potentially toxin-rich) blood from your stomach and intestines and sends it straight to the liver before it goes back to the heart. It’s a specialized detour. The liver acts like a customs office, checking everything you just ate for poisons or bacteria before allowing that blood to circulate to your brain and lungs. On a diagram of the veins in the body, this looks like a dense, purple-ish bush of vessels tucked behind your stomach.

Chronic Venous Insufficiency and the Map of Aging

As we age, the map changes. It’s inevitable. Gravity is a relentless opponent. Over time, the elasticity of the vein walls degrades. This is why you see more prominent veins in older adults. It isn't just "thin skin," though that's part of it. It’s the fact that the vessels themselves are distending.

Research from the Journal of Vascular Surgery suggests that nearly 40% of the population will deal with some form of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) by the time they hit 60. It starts with spider veins—those tiny "starbursts"—and can progress to heavy, aching legs or even skin ulcers.

The interesting thing? Your lifestyle writes the map.

If you stand all day, like a hairstylist or a teacher, you’re putting massive hydrostatic pressure on those leg valves. If you sit all day, you aren't using your "calf pump," which means the blood is just hanging out, stretching the vessel walls.

Visualizing the System for Better Health

When you look at a diagram of the veins in the body, don't just see it as a medical drawing. See it as a guide for maintenance.

We talk a lot about "clogged arteries" (atherosclerosis), but we rarely talk about "stretched veins." Yet, venous health is arguably more tied to our daily comfort. That heavy, "leaden" feeling in your legs at 5:00 PM? That is your venous system struggling to complete the map's loop.

📖 Related: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

Real-World Diagnostics

How do doctors actually use these maps? They don't just guess.

- Duplex Ultrasound: This is the gold standard. It uses sound waves to see the structure of the veins and the speed of the blood flow. It’s like a live-action version of a diagram of the veins in the body.

- Venography: They inject a special dye and use X-rays. It’s rarely done now because ultrasound is so good, but it provides an incredibly high-contrast "photo" of the map.

- CT/MRI Venography: Great for looking at the veins deep inside the chest or abdomen where ultrasound can't reach easily.

Actionable Steps: Keeping Your Map Clear

You can't change your genetics—some people just have "weak" vein walls—but you can change how the fluid moves through the map. It's mostly about managing pressure and assisting the return trip.

Movement is non-negotiable. If you’re stuck at a desk, do "toe curls" or "heel-toe" rocks every 30 minutes. It wakes up the calf pump. It’s a tiny movement that makes a massive difference in the pressure levels of your lower extremities.

Elevation works. It sounds like an old wives' tale, but lying down with your feet above your heart for 15 minutes a day uses gravity as an ally rather than an enemy. It "drains" the map.

Compression is a tool, not a punishment. Modern compression socks aren't the thick, beige monstrosities your grandma wore. They are engineered to provide graduated pressure—tightest at the ankle, loosening as they go up. This mechanically assists the valves in staying closed, preventing the backward "leakage" that causes most venous issues.

Hydration matters. Dehydration makes your blood "thicker" (more viscous), which makes it harder to push through the tiny capillaries and back into the venous system. Water keeps the flow smooth.

The next time you catch a glimpse of a diagram of the veins in the body, remember that those lines represent a hard-working return system. It’s a loop that never stops. Your heart might be the engine, but the veins are the road crew making sure the fuel gets back to the station. Treat them well, and they’ll keep that "map" running without a hitch for decades.

Practical Checklist for Venous Health

- Check your legs daily for new "spider" patterns or swelling that doesn't go away overnight.

- Invest in "graduated" compression for long flights or shifts where you’re on your feet for more than 4 hours.

- Prioritize "active" sitting. Shift your weight, cross and uncross your ankles, and never sit perfectly still for hours.

- Watch your sodium intake. Excess salt leads to water retention, which increases the volume of blood your veins have to carry, putting more stress on the valves.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Extra weight, especially around the midsection, puts physical pressure on the Inferior Vena Cava, making it harder for blood to exit the legs.