Africa is massive. You think you know how big it is, but you probably don't. When you look at a desert map of Africa, the sheer scale of the yellow and brown patches can be pretty overwhelming. Most people just see a giant sandbox at the top and maybe a smaller one at the bottom. It’s way more complicated than that.

Think about it.

The Sahara alone is roughly the size of the United States. If you laid a map of the US over North Africa, it would fit almost perfectly, stretching from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. But that's just the start of the story.

I’ve spent years looking at geographic data and geological surveys, and honestly, the way we teach African geography is kinda lazy. We talk about the Sahara like it’s a static wall of sand. It isn't. It’s a breathing, shifting organism that has been green, then dry, then green again over millions of years. This isn't just about sand dunes; it’s about rain shadows, tectonic shifts, and the cold currents of the Atlantic Ocean chilling the air until the clouds just give up.

Understanding the Desert Map of Africa Beyond the Sahara

When you pull up a desert map of Africa, your eyes go straight to the top. That’s the Sahara. It covers about 3.6 million square miles. That is a lot of ground. But look closer at the map. You’ll see it isn't just one big beach. You have the Libyian Desert, the Western Desert of Egypt, and the Tibesti Mountains.

The Sahara is actually mostly hamada. That’s a fancy word for barren, rocky plateaus. Only about 25% of it is actually covered in sand dunes, or "ergs." If you were to drive across it—which, honestly, is a logistical nightmare—you’d spend way more time bouncing over gravel and black rock than you would gliding over smooth orange sand.

Then you look south.

Way down in the southwestern corner, you find the Namib and the Kalahari. People mix these up all the time. The Namib is a "true" desert. It’s one of the oldest in the world, maybe even the oldest, dating back 55 to 80 million years. It sits right against the Atlantic. It’s famous for those massive red dunes at Sossusvlei. The Kalahari, which sits just to the east, is technically a semi-arid sandy savannah. It gets too much rain to be a "true" desert by most scientific definitions, but try telling that to someone hiking through its red sands in the middle of summer.

✨ Don't miss: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

The Weird Science of Why They Are There

Deserts don't just happen because it's hot. If that were the case, the Amazon would be a desert. It’s all about the "Hadley Cell." Basically, hot air rises at the equator, loses its moisture as rain, and then sinks back down around 30 degrees north and south latitude. That sinking air is dry. It squashes any chance of rain clouds forming.

That’s why the Sahara is where it is.

But the Namib is different. It exists because of the Benguela Current. This cold water comes up from Antarctica and cools the air above the ocean. Cold air can't hold much moisture. So, you get this eerie, thick fog that rolls over the dunes of Namibia, providing just enough water for weird plants like the Welwitschia mirabilis to live for over a thousand years, but never enough for actual rain. It’s a "fog desert." How cool is that?

The Sahel: The Border Nobody Talks About

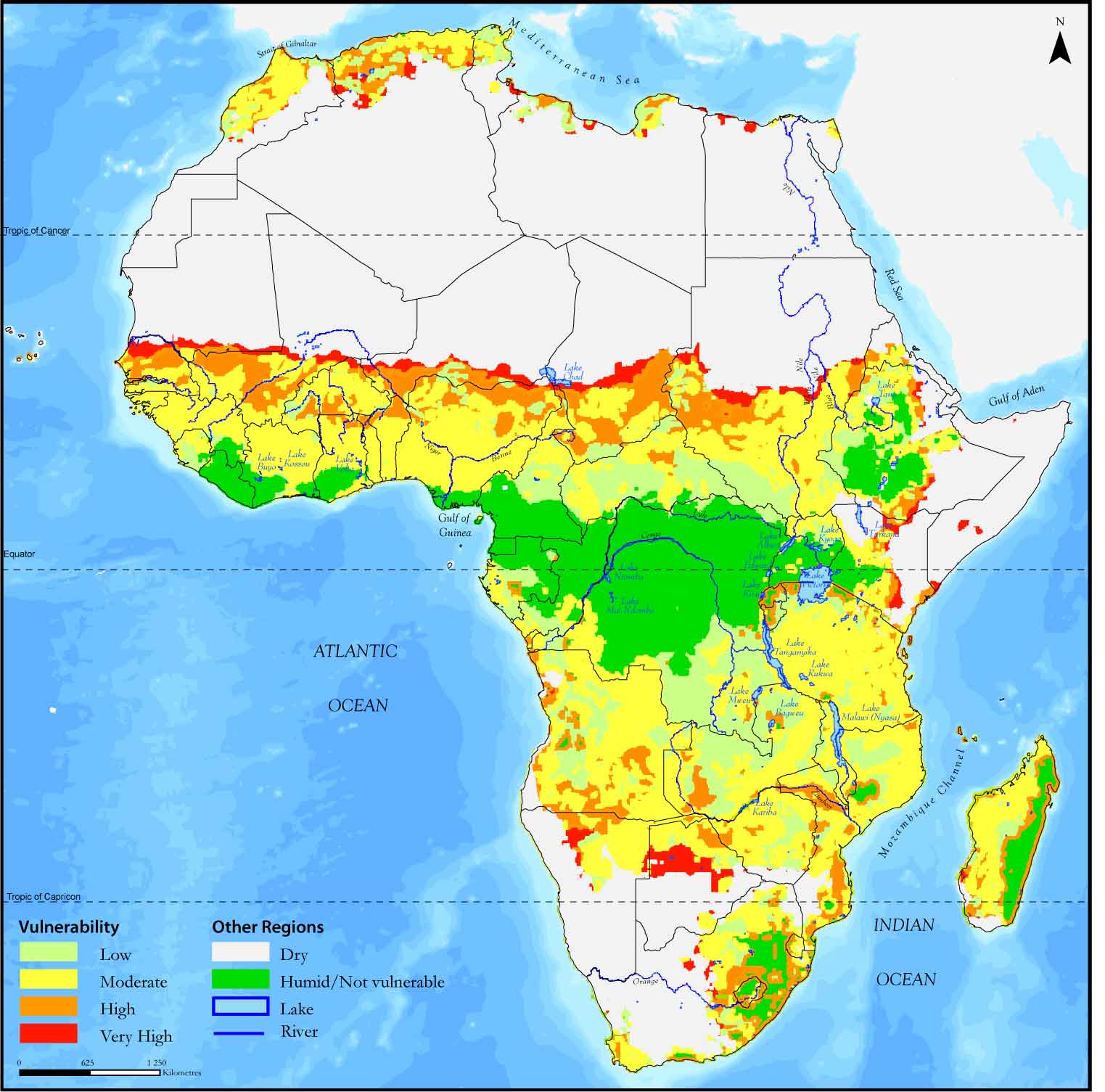

On any decent desert map of Africa, you’ll see a transition zone between the Sahara and the tropical savannas to the south. This is the Sahel. It’s a semi-arid belt of land that stretches across the continent from Senegal to Sudan.

It is the front line of desertification.

Basically, the Sahara is moving. It’s creeping south. Overgrazing and climate shifts are pushing the "green line" further down. This isn't just a geography fact; it’s a massive humanitarian issue. The "Great Green Wall" project is an actual thing where dozens of countries are trying to plant a 5,000-mile forest to stop the sand from taking over. It’s an ambitious, slightly crazy, and totally necessary attempt to redraw the map in real-time.

Surprising Pockets of Aridity

Did you know the Horn of Africa is mostly desert too? Look at Somalia and Ethiopia on the map. Despite being near the equator, this area—the Danakil Depression—is one of the hottest and driest places on Earth.

🔗 Read more: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

It’s a tectonic triple junction.

The earth is literally pulling apart there. You have lava lakes, sulfur springs that look like they belong on an alien planet, and salt flats that have been mined for centuries. It’s a desert born from volcanic heat and weird pressure, not just lack of rain.

Navigating the Map: What You Need to Know

If you’re actually planning to visit these places, don't just trust a basic Google Map. Navigation in the Sahara or the Kalahari requires specialized knowledge.

- The Sahara: It’s politically fragmented. Crossing from Algeria into Niger or Mali isn't like crossing a state line. Many areas are off-limits due to security risks. If you want the "Sahara experience," most people head to Merzouga in Morocco or the Siwa Oasis in Egypt.

- The Namib: This is the "easy" desert for travelers. Namibia is stable, the roads are mostly gravel but well-maintained, and you can actually climb the dunes.

- The Kalahari: Best experienced through the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (shared by South Africa and Botswana). It’s where you go to see lions with black manes.

The vegetation is also a giveaway on where you are on the map. In the Sahara, you’re looking for Date Palms near oases. In the Kalahari, it’s the Camel Thorn tree. In the Namib, it’s the Quiver Tree. These aren't just plants; they are survival markers.

Misconceptions About the Heat

"It’s a desert, so it’s always hot."

Wrong.

In the Sahara, temperatures can swing from 120°F during the day to freezing at night. Why? No clouds. Clouds act like a blanket. Without them, all the heat the ground soaked up during the day just radiates right back into space the second the sun goes down. If you’re camping in the desert, you need a heavy-duty sleeping bag, not just a t-shirt.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: What the Lake Placid Town Map Doesn’t Tell You

The Cultural Impact of the Arid Map

The desert map of Africa isn't just a physical thing. It’s a cultural one. The Tuareg people, known as the "Blue Men of the Sahara," have navigated these dunes for millennia. They don't use GPS. They use the stars, the shape of the dunes, and the "feel" of the wind.

To them, the desert isn't empty. It’s full of landmarks.

A specific rock formation or a dry riverbed (a "wadi") is as clear to them as a skyscraper is to a New Yorker. We look at a map and see a void; they see a complex network of highways and history.

Actionable Steps for Geographers and Travelers

If you are looking to truly understand or explore the African deserts, don't stop at a flat image.

- Use Satellite Imagery: Tools like Google Earth Pro allow you to see the "paleochannels"—ancient, dried-up rivers that used to flow through the Sahara. It’s the best way to see the "Green Sahara" of 10,000 years ago.

- Study the Rainfall Isohyets: Look for maps that show "isohyets" (lines of equal rainfall). This will tell you where the "true" desert ends and the semi-arid zones begin far better than a color-coded political map.

- Check the African Union’s Great Green Wall Progress: If you're interested in how the map is changing, follow the reports from the UNCCD (United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification). They provide the most accurate data on how the Sahara’s borders are shifting.

- Visit with Local Guides: Never, ever try to "self-drive" deep into the Sahara or the Namib without a satellite phone and a guide who knows the specific terrain. The desert doesn't forgive mistakes.

The African desert is a place of extremes, but it’s also a place of incredible beauty and historical depth. It’s not just "nothingness." It’s a complex environment that requires respect, study, and a very good pair of boots.

Study the terrain through topographic maps rather than just political ones to understand the elevation changes in the Atlas Mountains or the Hoggar Plateau, which significantly dictate the local climate. Compare the 1900s maps of the Lake Chad basin to current satellite data to see the most dramatic example of how water and desert interact over time. Always verify current political stability via official travel advisories before attempting any trans-Saharan routes.