You’re sitting in a doctor's office in Singapore or maybe a clinic in rural Brazil, and you hear it. That word. Some people say it like "den-gay." Others go with "den-gee." Honestly, it’s one of those medical terms that acts like a linguistic chameleon depending on where you're standing on a map.

It's confusing.

Dengue fever isn't just a tongue-twister; it’s a massive global health burden carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. But before we get into the literal aches and pains, let's settle the debate on how to actually say it. If you look at the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the "standard" American English pronunciation is DENG-gay (rhymes with "pay"). However, if you head over to the UK or Australia, you’re much more likely to hear DENG-gee (rhymes with "key").

Neither is technically "wrong" in a social sense, but the variation causes a lot of scratching of heads.

Why the World Can’t Agree on How to Say Dengue Fever

Languages are messy. The word itself likely comes from the Swahili phrase Ka-dinga pepo, which describes a cramp-like seizure caused by an evil spirit. When the Spanish got a hold of it, they thought it sounded like their word dengue, which means fastidious or "affectedly nice." Why? Because the joint pain from the virus makes people walk with a stiff, unnatural gait—almost like they’re trying to be overly posh or careful.

It’s kind of ironic. A disease that feels like your bones are snapping inside your body is named after a word for being "dainty."

In the Caribbean and Latin America, you'll hear the Spanish influence most clearly. In these regions, how to say dengue fever is almost universally "DEN-gay." The emphasis hits that first syllable hard. Meanwhile, in many parts of Southeast Asia—where the virus is incredibly common—the British colonial influence often leaves people saying "DENG-gee."

📖 Related: Why PMS Food Cravings Are So Intense and What You Can Actually Do About Them

The Breakbone Fever Connection

If you want to sound like an old-school tropical medicine expert, you might call it "breakbone fever." This isn't just a scary nickname. It's a literal description of the sensation. People who have survived a bad bout of it often describe a deep, throbbing pain in their bones that makes them feel like they’ve been hit by a truck.

Dr. Benjamin Pinsky, an expert in infectious diseases at Stanford, often notes that clinical presentations can vary, but the "crushing" pain is a hallmark. When you're talking to a medical professional, using the term "dengue" (however you pronounce it) is better, but knowing the "breakbone" moniker helps you understand the severity of what's actually happening inside the body.

What Really Happens When You Get Bit

It starts with a mosquito. Not just any mosquito, but the Aedes species, which is recognizable by the white markings on its legs. These bugs are day-biters. Most people think they only need to worry about mosquitoes at dusk, but that’s just not true with this virus.

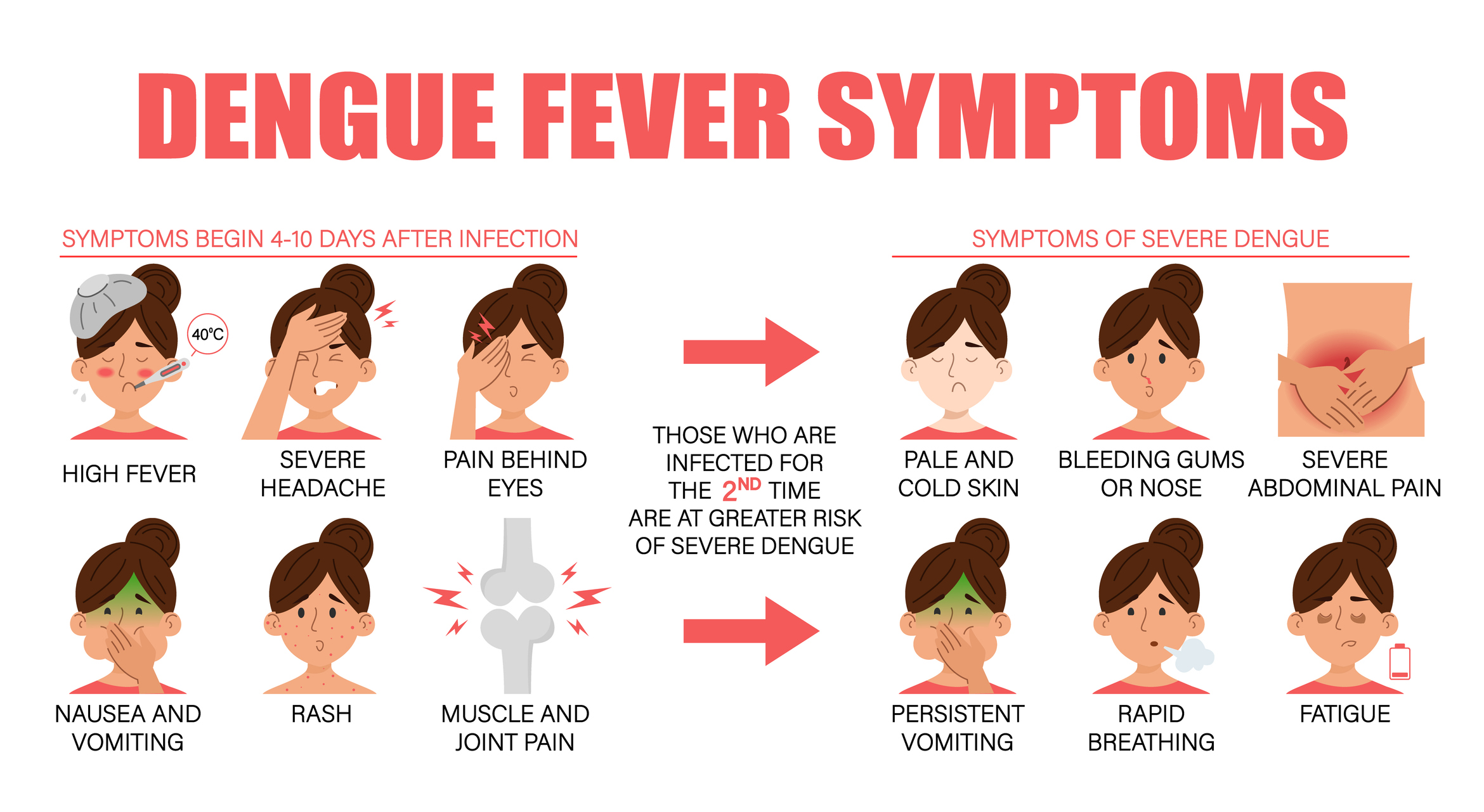

Once the virus enters your bloodstream, there’s an incubation period. Usually about 4 to 10 days. Then, the hammer drops.

- A sudden, high fever (often reaching 104°F or 40°C).

- Severe headaches, specifically right behind the eyes.

- Nausea and vomiting that won't quit.

- A rash that can appear a few days after the fever starts.

Most people recover in a week or two. But—and this is a big but—there’s a secondary version called Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. This is where things get life-threatening. Your blood vessels start leaking, and your platelet count drops. It’s why prompt medical attention is so critical. If you start seeing small purple spots on your skin or your gums start bleeding, you aren't just "sick" anymore. You’re in a medical emergency.

The Global Spread: It’s Not Just a Tropical Problem Anymore

For a long time, people in the US or Europe looked at this as a "traveler's disease." You went to Thailand, you got sick, you came home. That's changing. Thanks to rising global temperatures and increased urbanization, the mosquitoes are moving.

👉 See also: 100 percent power of will: Why Most People Fail to Find It

We’ve seen local transmission in Florida, Texas, and even parts of Southern Europe like France and Italy. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been ringing the alarm bells for years. They estimate that nearly half the world's population is now at risk. That's a staggering number.

Basically, the climate is becoming more "mosquito-friendly."

Myths That Need to Die

There is so much bad advice out there. I've heard people say that eating papaya leaves will cure you. While some small studies in places like Malaysia have looked at papaya leaf extract for raising platelet counts, it is not a cure. You can't just drink a smoothie and expect the virus to vanish.

Another big one: "I've had it once, so I'm immune."

Actually, the opposite is true. There are four different serotypes of the virus (DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, and DEN-4). If you get DEN-1, you’re immune to that specific one for life. But if you get bit a year later by a mosquito carrying DEN-2, you are actually at a higher risk for the severe, hemorrhagic version. It’s a phenomenon called Antibody-Dependent Enhancement. Your body's previous antibodies actually help the new version of the virus enter your cells more easily.

It’s cruel, honestly. Your immune system tries to help but ends up making the situation worse.

✨ Don't miss: Children’s Hospital London Ontario: What Every Parent Actually Needs to Know

How to Protect Yourself (Without Living in a Bubble)

Prevention isn't just about bug spray, though that’s a huge part of it. You need the stuff with DEET or Picaridin. Natural oils might smell nice, but they don't hold up against a determined Aedes mosquito.

Think about your environment. These mosquitoes love "artificial containers." That means the saucer under your flower pot, the old tire in the backyard, or even a discarded bottle cap filled with rainwater. They only need a tiny amount of water to lay eggs.

- Empty standing water. Do it once a week. Every week.

- Wear long sleeves. Even if it’s hot. Light-colored clothing is better because mosquitoes are attracted to dark colors.

- Use window screens. It sounds basic, but it's the first line of defense.

- Vaccination? It’s complicated. There is a vaccine called Dengvaxia, but the WHO generally recommends it only for people who have already had the virus once before (due to that weird immunity issue mentioned earlier).

Actionable Steps for the "Breakbone" Season

If you live in or are traveling to an endemic area, your strategy needs to be proactive rather than reactive.

First, check the local health department websites for "outbreak alerts." If you’re in the US, the CDC keeps a running tally of cases. If you start feeling a fever, do not take aspirin or ibuprofen. This is a huge mistake people make. These drugs are blood thinners, and since the virus can cause bleeding issues, taking them can actually trigger a hemorrhage. Stick to Acetaminophen (Tylenol) for the fever.

Second, if you’re traveling, don’t just pack DEET; pack a permethrin spray for your clothes. It’s a synthetic insecticide that stays on the fabric through several washes. It’s like wearing a shield.

Finally, stay hydrated. The biggest reason people end up in the hospital with this virus isn't the fever itself—it's the dehydration that comes from the vomiting and the high body temperature.

Whether you say "den-gay" or "den-gee," the most important thing is recognizing the symptoms early. Don't wait for the rash. Don't wait for the bone-crushing pain to become unbearable. If you've been in a mosquito-heavy area and your temperature spikes, get to a clinic. Blood tests can confirm the virus quickly, and while there’s no specific "antiviral" pill for it, supportive care—like IV fluids—makes all the difference in the world.

Watch the water, wear the spray, and keep an eye on your symptoms. That’s how you handle this, regardless of the pronunciation.