August 2, 1985, started out as a pretty standard summer day in North Texas. It was hot. It was muggy. If you’ve ever spent a summer afternoon at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, you know the drill: the sky gets that heavy, bruised look, and the air feels like a wet wool blanket.

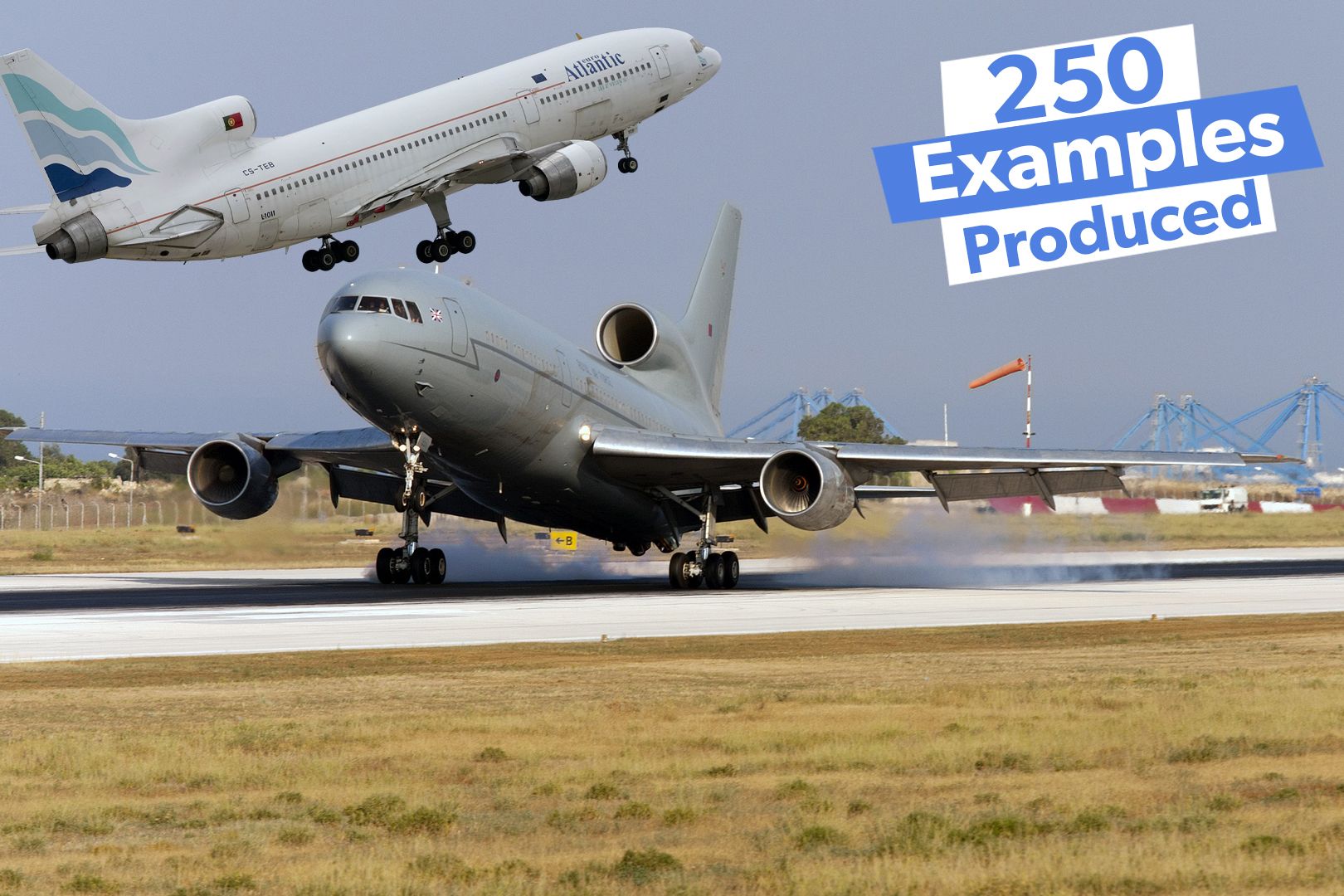

Delta Air Lines Flight 191 was just one of hundreds of flights scheduled to land that evening. The Lockheed L-1011 TriStar was a beast of a plane—a wide-body workhorse that pilots generally loved because it felt stable. But by 6:05 PM, that stability didn't matter. The plane was slammed into the ground by a weather phenomenon that, at the time, most pilots barely understood. It changed aviation forever. Honestly, if you’ve flown through a thunderstorm in the last thirty years and felt the plane suddenly surge or dip but stayed safely in the air, you probably owe your life to the lessons learned from this specific crash.

What Really Happened on the Approach to DFW?

Capt. Edward "Ted" Connors was at the controls. He was experienced. The crew was professional. They were coming in from Fort Lauderdale and everything seemed fine until they got close to the airport.

There was a localized thunderstorm sitting right over the approach path. Now, today, we see red on a radar and we go around. In 1985? Pilots flew through "cells" all the time if they thought they could handle it. As Delta Air Lines Flight 191 descended, it entered an isolated convective cell.

Suddenly, the airspeed went nuts.

First, the plane hit a massive increase in headwind. The pilots did what they were trained to do: they reduced power to keep the plane from overshooting the runway. But then, the wind didn't just shift; it collapsed. The plane flew out of the headwind and directly into a massive downdraft—a "microburst."

The wind was literally pushing the aircraft toward the dirt at a terrifying rate.

The TriStar hit a field about a mile north of Runway 17L. It bounced. It crossed Highway 114, and in a horrific stroke of bad luck, the engine struck a passing car, killing the driver, William Mayberry. The plane then veered, slammed into two massive water tanks on the airport grounds, and exploded.

137 people died. It remains one of the most studied accidents in the history of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

The Invisible Killer: Microbursts and Wind Shear

Before Delta Air Lines Flight 191, "wind shear" was a term people knew, but they didn't really respect it the way they do now.

💡 You might also like: USA Map Major Cities: What Most People Get Wrong

Dr. Ted Fujita—the guy who invented the Fujita Scale for tornadoes—had been screaming about microbursts for years. He described them as "starbursts" of wind that hit the ground and spread out in all directions. Imagine taking a garden hose, pointing it straight at the sidewalk, and watching the water blast outward. That’s a microburst.

If a plane flies through it, it first gets a lift (headwind), then a massive sink (downdraft), then a huge push from behind (tailwind).

The tailwind is the killer.

It drops your airspeed so fast that the wings just stop producing lift. You stall. You fall.

The NTSB report on Flight 191 was a wake-up call that couldn't be ignored. The industry realized that even the best pilots in the world couldn't "hand-fly" their way out of a severe microburst if they didn't have the right data.

Why technology had to catch up

Back then, the radar on the planes was mostly used to find rain. It couldn't see the wind. After DFW, NASA and the FAA poured millions into something called Terminal Doppler Weather Radar (TDWR).

- It detects the movement of dust and moisture in the air.

- It calculates wind speed shifts in real-time.

- It gives controllers an "alert" they can relay to pilots immediately.

If you’ve ever been sitting on the tarmac and the pilot says, "We’re holding for 20 minutes because of wind shear alerts," that is the legacy of Flight 191 in action.

The Human Element: Why Didn't They Go Around?

It’s easy to look back with 20/20 hindsight and say, "Why did they fly into a storm?"

But you have to understand the culture of the 80s. Aviation was still evolving out of the "cowboy" era. There was a huge push for on-time arrivals. Also, the onboard radar on the L-1011 had a flaw—it could be "blinded" by heavy rain. The pilots saw rain, but they didn't see the violent turbulence hidden inside it.

📖 Related: US States I Have Been To: Why Your Travel Map Is Probably Lying To You

There was also a bit of a communication gap. Another plane had gone through that same area just minutes before and made it. The Delta crew heard that. They figured if the guy in front of them was okay, they would be too.

It’s a classic case of "normalization of deviance." You do something slightly risky, it turns out fine, so you do it again. Until it isn't fine.

The Long-Term Impact on Your Next Flight

If there is any "good" to come from 137 lives lost, it’s the sheer volume of safety mandates that followed.

First, Crew Resource Management (CRM) was overhauled. This is the fancy way of saying "teaching pilots how to talk to each other." It encouraged co-pilots to speak up if they saw something wrong. In Flight 191, the cockpit recordings showed some hesitation. Today, if a junior officer sees a red flag, they are trained to be assertive.

Second, the installation of LLWAS (Low-Level Windshear Alert System) at airports. If you look around the perimeter of a major airport like DFW, ATL, or ORD, you’ll see these poles with anemometers on them. They are literally measuring the wind every few seconds to catch a microburst before a plane hits it.

Third, the "Windshear Recovery Maneuver." Every airline pilot now trains for this in the simulator. They practice what to do if the bottom drops out. You firewall the engines, you pitch the nose up to the stick shaker, and you don't touch the configuration. You fly the wing.

Myths and Misconceptions

A lot of people think the plane "fell out of the sky" because of mechanical failure.

Nope.

The L-1011 was performing exactly as it was designed to. The engines were screaming. The control surfaces were moving. The weather was simply more powerful than the physics of the aircraft at that specific altitude and speed.

👉 See also: UNESCO World Heritage Places: What Most People Get Wrong About These Landmarks

Others think the pilots were being reckless.

That’s also not really fair. They were following the standard operating procedures of 1985. The problem was that the procedures themselves were insufficient for the atmospheric reality of North Texas thunderstorms.

The Highway 114 Factor

One of the most surreal parts of this story is the car on the highway. Most plane crashes happen in remote areas or on airport property. Flight 191 hit a commuter.

This led to a massive rethink of how we design "clear zones" around runways. It's why you often see massive grassy buffers or sunken highways near major international airports now. We try to keep the kinetic energy of a potential accident away from the general public.

What This Means for You Today

Traveling is stressful enough without worrying about the weather. But here is the reality: flying is exponentially safer now because we stopped guessing about the wind.

When you see a thunderstorm out the window of your terminal, you aren't just relying on the pilot's "gut feeling." You are relying on a multi-layered network of Doppler radar, ground sensors, and predictive algorithms that didn't exist in 1985.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Traveler:

- Trust the "Hold": If your flight is delayed for "weather at the destination" even if it looks sunny where you are, it’s often because of wind shear sensors at the arrival airport. Let them do their job.

- The 15-Minute Rule: Most microbursts are short-lived. They peak and dissipate in about 15 to 20 minutes. A short delay is usually all it takes for the danger to pass completely.

- Respect the L-1011: While the plane is no longer in passenger service, it remains a marvel of engineering. The Flight 191 accident wasn't a "faulty plane" issue—it was a "lack of data" issue.

- Pay Attention to the Safety Briefing: It sounds cliché, but Flight 191 had survivors. Many of them survived because they were in the tail section, which broke away from the main fireball. Knowing your exits and keeping your seatbelt low and tight makes a literal difference in high-impact scenarios.

The crash of Delta Air Lines Flight 191 was a dark day for aviation, but it forced the hand of regulators and scientists. It turned the "invisible killer" of wind shear into a visible, avoidable threat. We don't fly the same way we did in 1985, and we are all much safer for it.

Check your flight's status via the airline's app rather than just the gate screens, as digital updates on weather holds are often more detailed. If you’re interested in the technical side, the NTSB's full digital archive on the Flight 191 investigation is public and provides a deep look into the flight data recorder transcripts that changed pilot training forever.