You’ve got a killer idea. Maybe it’s a decentralized app, a ergonomic chair, or a new way to process lithium batteries. Your brain is already at the finish line, imagining the polished product sitting on a shelf or winning an Apple Design Award. But honestly? You’re nowhere near that. You’re at the messy, confusing, and slightly embarrassing stage where you need a prototype.

People get the definition of a prototype wrong all the time. They think it’s just a "beta" or a "pre-release version." It isn't.

A prototype is a question, not a product. It’s a physical or digital manifestation of a hypothesis. When you build one, you aren't trying to show off how great your idea is; you’re trying to find out exactly where it breaks. If you aren't breaking things, you're just playing house.

What is the actual definition of a prototype?

In the strictest sense, the definition of a prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It comes from the Greek prototypon, meaning "primitive form." It’s the first of its kind. But let’s look at how this actually plays out in the real world.

In engineering, a prototype might be a "mule"—a vehicle that looks like a scrap heap on the outside but carries the high-tech drivetrain of a future supercar. In software, it might be a "wireframe" that doesn't actually have a database behind it. You click a button, and it just shows a static image of what would happen if the code actually existed.

The goal is validation. You’re trying to reduce uncertainty. The more uncertainty you have, the more "lo-fi" your prototype should be. If you spend $100,000 building a high-fidelity prototype before you even know if people want the service, you’ve failed the fundamental logic of product development.

The spectrum of "faking it"

Not all prototypes are created equal. You’ve got different levels of "realness" depending on what you need to learn.

👉 See also: Why Use a Rise Over Run Slope Calculator When You Could Just Do the Math (But Probably Shouldn't)

Low-fidelity (Lo-fi) Prototypes

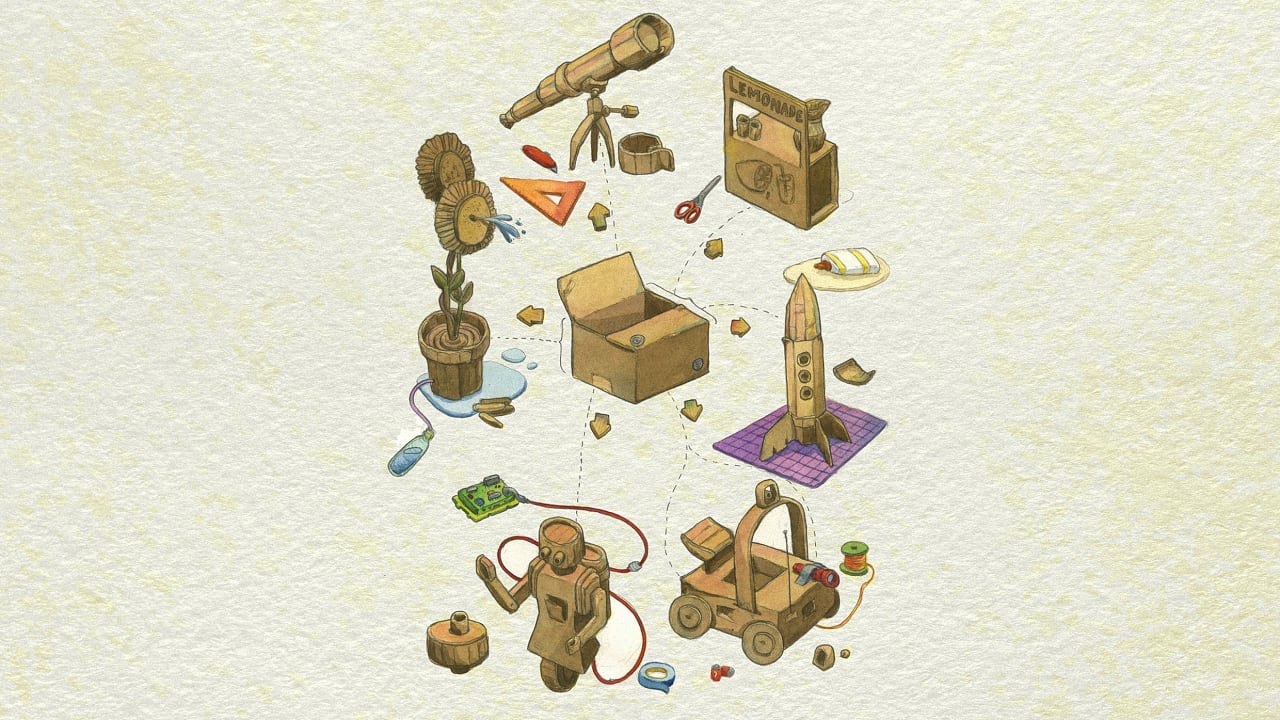

These are the sketches on napkins. It’s the cardboard VR headset Google famously used before Cardboard was an actual product. It’s cheap. It’s fast. You can throw it in the trash without crying. Designers at IDEO often talk about "thinking with your hands." If you can't explain it with some duct tape and a Sharpie, you probably don't understand the core problem yet.

High-fidelity (Hi-fi) Prototypes

This looks and feels like the real thing. If it’s an app, the animations are smooth. If it’s a physical tool, it’s 3D printed with the right weight and balance. Use these when you need to test usability or pitch to investors. But be careful. If you show a hi-fi prototype too early, people will give you feedback on the font color instead of the actual functionality. They get distracted by the shiny bits.

Real-world examples of the definition of a prototype in action

Look at the original prototype for the Palm Pilot. Jeff Hawkins, the founder, carried a block of wood in his pocket for weeks. He carved it to the size he thought a handheld computer should be. When he wanted to "check his calendar," he’d pull out the wood and tap on a piece of paper glued to the front. He wasn't testing the chips or the screen; he was testing the form factor. Would he actually carry this thing? That’s a prototype.

Then you have SpaceX. Their Starship program is basically prototyping at scale. They build a "Starhopper," fly it a few hundred feet, and let it explode. They learn about the welds, the raptor engines, and the vibrations. Then they build the next one. Each "ship" is a prototype. The definition of a prototype here is "something we expect to lose in the name of data."

Why most people fail at prototyping

The biggest mistake? Falling in love with the prototype.

It happens to the best of us. You spend three days coding a specific feature for a mockup, and suddenly you’re emotionally attached to it. When a user tells you they don't need that feature, you get defensive. You start explaining why they need it.

✨ Don't miss: How to record tv shows: Why the DVR isn't actually dead yet

Stop.

If you have to explain your prototype, it’s already failed. The point is to observe. Watch the user struggle. Watch where they click. If they get frustrated, that’s gold. That’s the data that saves you from a multimillion-dollar mistake later.

Another trap is "feature creep" in the prototype. You think, "Well, if I'm building the login screen, I might as well build the password reset flow and the social media integration." No. Just don't. Every hour you spend on non-essential features is an hour you aren't testing the "riskiest assumption."

What is the one thing that, if it doesn't work, kills the whole business? Test that first.

The "Wizard of Oz" method

This is a classic in the tech world. You build a front end that looks automated, but there’s actually a human in the back doing the work manually.

When Aardvark (a social search engine later bought by Google) started, they didn't have a complex AI to route questions. When a user sent a query, employees literally sat in a room, searched the web, and typed back the answer. The users thought they were interacting with a brilliant algorithm. The founders were just testing if people actually liked getting answers this way.

It was a prototype of the experience, not the technology.

Engineering vs. Design Prototypes

In the world of hardware, we often distinguish between "Works-Like" and "Looks-Like" prototypes.

✨ Don't miss: Why Live Doppler Radar for My Location is Often Wrong (and How to Fix It)

- The Works-Like Prototype: This is the "breadboard" version. Wires everywhere. Soldering that looks like a bird's nest. It’s ugly as hell, but it proves the circuit works. It proves the mechanical linkage can lift the required weight.

- The Looks-Like Prototype: This is a "dummy" model. It has no internals. It’s often a solid block of resin or plastic painted to look like the final product. You use this for photo shoots, ergonomic testing, and retail placement discussions.

Eventually, these two paths converge into a "Pre-production Prototype," which is the final boss of the prototyping world. This is where you test the actual manufacturing process. Can the factory in Shenzhen actually build this at scale?

Functional Fixedness and the Prototype Mindset

There’s a psychological concept called "functional fixedness." It’s the mental block that prevents you from using an object in a new way. Prototyping is the cure for this.

When you’re in the thick of it, you’ll find that your "perfect" solution is actually a hindrance. Maybe you thought the user needed a dashboard, but the prototype reveals they really just need a weekly email. If you hadn't built the "dumb" version first, you’d have spent six months building a dashboard nobody logs into.

The Role of Fidelity in Feedback

There is a weird quirk in human psychology regarding how we critique things. If you show someone a rough sketch, they feel comfortable giving you "big picture" feedback. They’ll say things like, "I think this whole section is unnecessary," or "What if the user starts here instead?"

The moment you show them a high-resolution, pixel-perfect mockup, their brain switches gears. They start talking about the shade of blue or the kerning of the text. They assume the "big" decisions have already been made because it looks so finished.

If you want honest, structural feedback, keep your prototype ugly. Use "Comic Sans" if you have to. Make it clear that everything is up for debate.

Practical Steps for Your First Prototype

Don't go out and buy a 3D printer today. Don't hire a full-stack developer yet.

Start by defining your Riskiest Assumption. Is it that people will pay $20 for this? Is it that the battery will last 24 hours? Is it that the API will respond fast enough?

Once you have that, build the smallest possible thing to test only that assumption.

- If it's a service: Use a landing page with a "Sign Up" button. If people click it, you have a prototype of demand.

- If it's an app: Use Figma or even PowerPoint to link screens together.

- If it's hardware: Use cardboard, foam core, or existing parts from other products.

Document everything. Take photos of the failures. The "definition of a prototype" isn't just the object you build; it’s the trail of data you leave behind. Each iteration should be a deliberate step away from ignorance and toward a viable product.

Remember that the most famous products in the world started as "garbage" versions. The first version of Dyson’s vacuum went through 5,127 prototypes. Most of them didn't work. That wasn't failure; that was the process.

To get started, list the three biggest "maybes" in your project. Pick the one that scares you the most. Now, find a way to test it by Monday using only the tools you already have on your desk. That is your prototype. Stop talking about it and go break something.

Next Steps for Implementation

- Identify the Core Variable: Isolate the one feature or function that is most critical to your project's success.

- Choose Your Fidelity: Match your tools to your goals—use paper for flow, 3D printing for form, and "Wizard of Oz" methods for service logic.

- Set a "Kill" Criteria: Decide before you test what results would mean the idea isn't worth pursuing in its current form.

- Gather Unbiased Testers: Find people who aren't your friends or family to interact with the prototype while you remain silent and observe.

- Iterate Immediately: Take the friction points discovered during testing and sketch a solution within 24 hours while the observations are fresh.