When you look at your hand, or the screen you’re reading this on, or even the air you're breathing, you’re looking at a massive, microscopic tug-of-war. Everything is held together by invisible connections. Specifically, we're talking about how we define the covalent bond. It’s the most common way atoms stick together in the organic world. Without it, you’d literally be a puddle of unrelated atoms. No DNA. No water. Just chaos.

Honestly, it’s all about stability. Atoms are a lot like people—they’re looking for a sense of completion. Most atoms have this desperate need to fill their outer electron shells. It's called the octet rule. They want eight electrons. If they don't have eight, they’re reactive. Unstable. They’re "lonely" in a chemical sense. To fix this, they find a partner. But instead of one atom stealing from the other (that's ionic bonding, which is more like a robbery), they decide to share.

✨ Don't miss: iRobot Roomba Combo Essential: What Nobody Tells You Before You Buy

What Does it Really Mean to Define the Covalent Bond?

To define the covalent bond in the simplest terms possible: it’s a chemical link between two atoms where they share at least one pair of electrons. Think of it as a handshake that neither person wants to let go of because they both need the other person's hand to feel "whole."

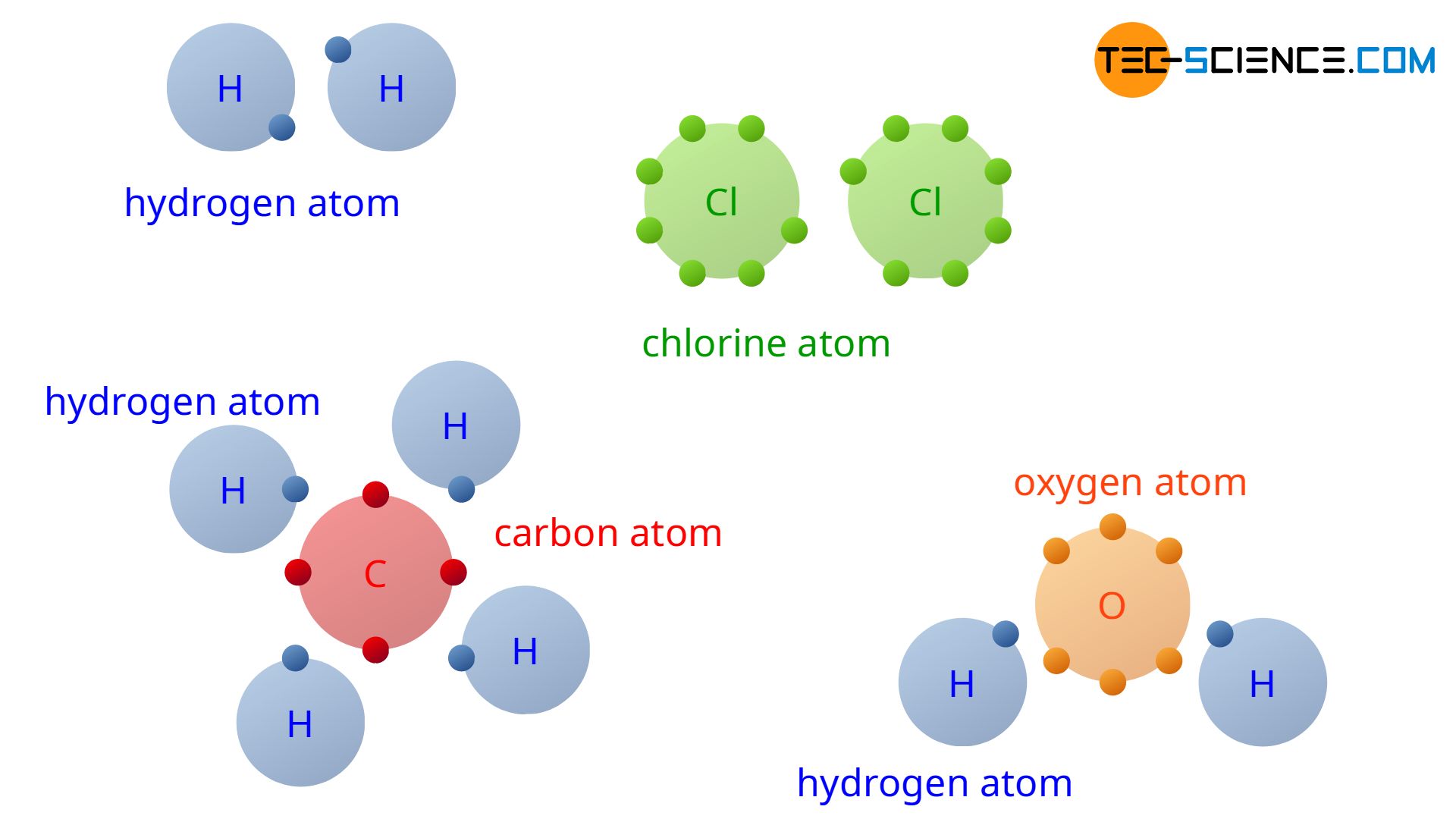

Usually, this happens between non-metal atoms. Why? Because non-metals have high electronegativity. They’re "greedy" for electrons. Since neither atom is strong enough to completely yank the electron away from the other, they settle for a middle ground. They share. This shared pair of electrons lives in the space between the two nuclei, effectively glueing them together.

The Physics of the Tug-of-War

It’s a delicate balance. You have the positive charge of the nuclei pulling on the negative charge of the electrons. If they get too close, the two nuclei (both positive) start to repel each other. If they’re too far apart, the attraction isn't strong enough. The bond length is that "sweet spot" where the energy is lowest and the system is most stable.

Linus Pauling, a giant in the world of chemistry and a double Nobel Prize winner, spent a huge chunk of his life figuring out exactly how these bonds work. He introduced the concept of electronegativity. If you want to understand the nuance of how we define the covalent bond, you have to understand that not all sharing is equal.

When Sharing Isn't Fair: Polar vs. Nonpolar

Sometimes atoms are jerks. In a "pure" covalent bond, like when two Hydrogen atoms ($H_2$) get together, they share perfectly. They have the exact same electronegativity. Neither pulls harder. This is a nonpolar covalent bond. It’s a perfect 50/50 split.

👉 See also: Metal Cutting Circular Saw Blade: Why Your Teeth Keep Snapping and How to Fix It

But then you have molecules like water ($H_2O$). Oxygen is an electron hog. It has a much higher electronegativity than Hydrogen. So, while they are "sharing" electrons, the electrons spend way more time hanging out near the Oxygen nucleus. This creates a polar covalent bond. The Oxygen side gets a slightly negative charge ($\delta-$), and the Hydrogen side gets a slightly positive charge ($\delta+$).

This "unfair sharing" is why water behaves the way it does. It’s why water has surface tension and why ice floats. Without the polar nature of the covalent bond, life as we know it would be physically impossible. The "stickiness" of water is just the result of covalent bonds being a little bit lopsided.

Sigma, Pi, and the Geometry of Reality

We can't just talk about "lines" between atoms. It's 2026; we know atoms aren't little balls on sticks. They are clouds of probability.

When you define the covalent bond at a college or professional level, you start talking about orbital overlap.

- Sigma Bonds ($\sigma$): This is the first bond formed. It’s a head-on overlap. It’s strong. It allows the atoms to rotate freely, like two wheels on a single axle.

- Pi Bonds ($\pi$): These happen in double or triple bonds. It’s a side-to-side overlap of p-orbitals. These are more rigid. If you have a pi bond, the molecule can't rotate. This "stiffness" determines the shape of proteins and the strength of plastics.

Think about Nitrogen gas ($N_2$). It makes up about 78% of the air you're breathing right now. It has a triple bond—one sigma and two pi bonds. That bond is so incredibly strong that most organisms can't break it. We’re drowning in Nitrogen but starving for it because the covalent bond is too tough to crack. Only specific bacteria (and humans using the energy-intensive Haber-Bosch process) can rip those atoms apart.

Real-World Examples: From Diamonds to DNA

Diamonds are just carbon atoms. That's it. But they are arranged in a tetrahedral lattice where every single Carbon atom is covalently bonded to four others. It's a continuous network. This is why diamonds are the hardest natural material. You aren't just breaking a "link"; you're trying to break a macroscopic web of shared electrons.

💡 You might also like: That Windows Blue Screen Sad Face: What It’s Actually Trying to Tell You

Then look at DNA. The rungs of the DNA ladder? Those are hydrogen bonds (weaker). But the "backbone"—the actual structural rails of the ladder? Those are covalent bonds. If those bonds weren't incredibly stable, your genetic code would dissolve every time you took a hot shower.

Why This Matters for Modern Tech

We are currently using our understanding of how to define the covalent bond to build the next generation of materials. Carbon nanotubes and graphene are essentially just sheets of covalent bonds. They are 100 times stronger than steel but light as a feather.

In the world of pharmaceuticals, drug design is basically just "covalent engineering." Scientists try to design molecules that will covalently bond to a specific "bad" protein in your body, permanently turning it off. This is how many irreversible inhibitors work. You’re essentially welding a "lock" onto a "keyhole" so the disease can't function.

How to Identify a Covalent Bond in the Wild

If you're trying to figure out if a substance is held together this way, look for these signs:

- Low Melting Points: Compared to ionic compounds (like salt), most covalent molecules (like sugar or wax) melt pretty easily because the forces between the molecules are weak, even if the bonds inside are strong.

- Poor Conductivity: Electrons are trapped in the bond. They aren't free to roam around, so most covalent substances don't conduct electricity well.

- Physical State: They can be gases ($CO_2$), liquids ($H_2O$), or soft solids (paraffin).

Misconceptions to Toss Out

People often think covalent bonds are "weaker" than ionic ones. That’s not really true. If you look at a "network covalent solid" like quartz or diamond, they are way tougher than any ionic crystal. The strength depends entirely on the environment and the atoms involved.

Another weird one: the idea that electrons are like "points" moving in a circle. They aren't. When we define the covalent bond, we’re talking about a shared "cloud" or a wave function. The electron is essentially in two places at once until it's measured.

Summary of Actionable Insights

If you’re studying this for a class or just trying to sound smart at a dinner party (good luck with that), keep these three things in mind:

- Check the Electronegativity: Use a periodic table. If the atoms are close to each other on the right side (non-metals), it’s almost certainly covalent.

- Look for Polarity: If the atoms are different (like Carbon and Oxygen), the bond is polar. If they are the same (like Oxygen and Oxygen), it's nonpolar. This dictates if the substance will dissolve in water or oil.

- Count the Bonds: Single bonds are long and "weak" (relatively speaking). Triple bonds are short, incredibly strong, and keep the molecule rigid.

To really master the concept, try to visualize the electron density. Don't think of it as a string connecting two balls. Think of it as a fog that gets thickest right between the two atoms, pulling them toward each other so they don't fly off into the void. Understanding this "sharing" is the key to understanding why the physical world doesn't just crumble into dust.

Next Steps for Deep Learning:

- Download a PDB viewer (Protein Data Bank) and look at the covalent backbone of a simple protein like Insulin to see how these bonds create 3D structures.

- Review the Pauling Scale of electronegativity; if the difference between two atoms is less than 1.7, you're looking at a covalent bond.

- Experiment with solubility: Try mixing oil (nonpolar covalent) and water (polar covalent) to see the physical consequences of "unfair sharing" in real-time.