Math often feels like a series of arbitrary hurdles designed to make middle schoolers sweat, but some concepts actually stick because they're the literal backbone of how we process information. If you've ever tried to define the associative property, you probably remember a textbook definition involving parentheses and variables like $a, b,$ and $c$. Boring, right? But here’s the thing: without this property, your calculator would be a paperweight, and computer programming would be a nightmare of manual grouping.

Basically, the associative property is the rule that says when you’re adding or multiplying numbers, the way you group them doesn't change the final result. You can shift the focus. It’s about the "association" or the "grouping." It doesn't matter if you tackle the first two numbers first or the last two; the sum or product stays identical.

The Raw Mechanics: What It Actually Looks Like

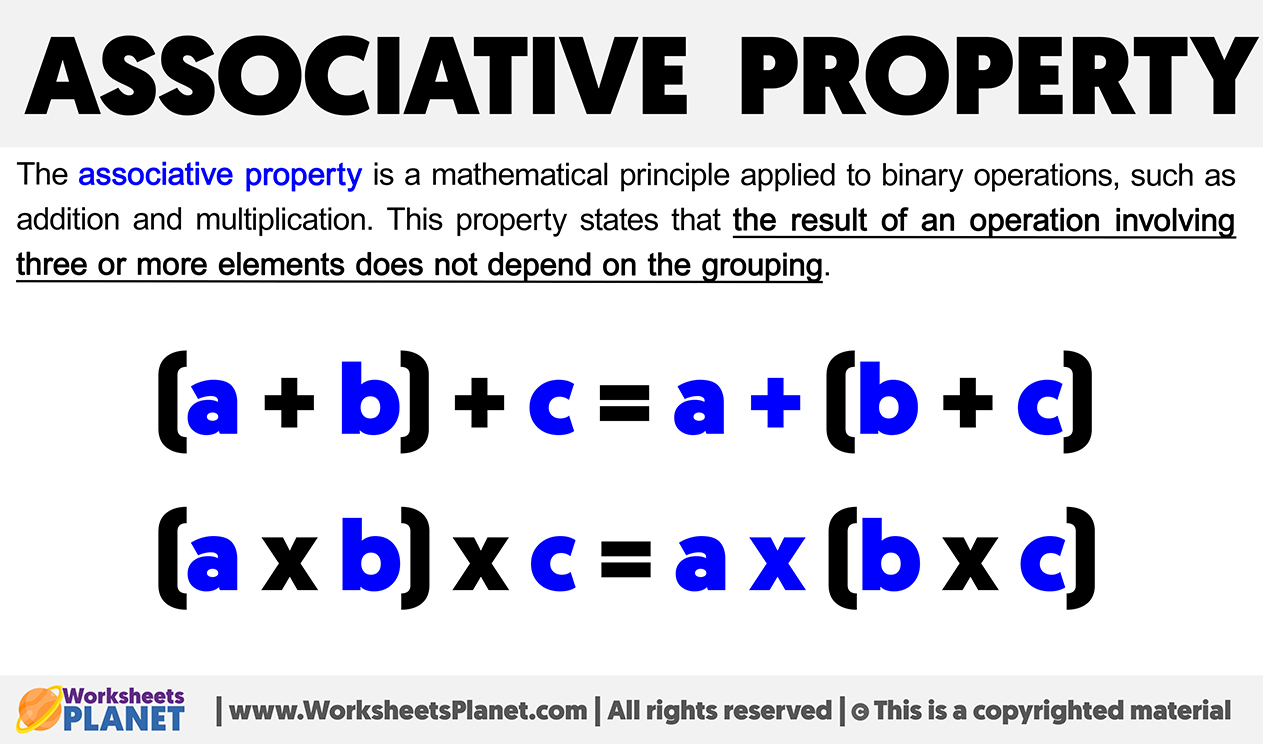

Let's get the formal stuff out of the way. In the world of arithmetic, we primarily apply this to addition and multiplication.

For addition, the rule is expressed as:

$$(a + b) + c = a + (b + c)$$

Think about it this way. Imagine you’re at a coffee shop. You buy a $5 latte, a $3 cookie, and a $2 bottle of water. If you pay for the latte and cookie together ($8) and then add the water, you’ve spent $10. If you buy the cookie and water together ($5) and then add the latte, you’ve still spent $10. The result is stubborn. It refuses to change just because you changed your mental grouping. This is why we say addition is "associative."

Multiplication works exactly the same way:

$$(a \times b) \times c = a \times (b \times c)$$

If you have two boxes, each containing three bags, and each bag has four apples, how many apples do you have? You could multiply the boxes and bags first ($2 \times 3 = 6$) and then multiply by the apples ($6 \times 4 = 24$). Or, you could find the apples per box first ($3 \times 4 = 12$) and multiply by the number of boxes ($12 \times 2 = 24$). Same outcome.

Where People Get Tripped Up

Honestly, people often confuse the associative property with the commutative property. They sound similar, and they both deal with how we rearrange things, but they are fundamentally different tools in your math kit.

The commutative property is about order. It says $2 + 3$ is the same as $3 + 2$. The associative property, however, is strictly about grouping. It assumes the order of the numbers stays exactly the same, but the "brackets" or the sequence of operations moves.

Think of the commutative property as "moving" the numbers, while the associative property is "moving" the parentheses.

Here is a weird nuance: subtraction and division are not associative. This is where most students—and even some adults—hit a wall. If you try to change the grouping in subtraction, the whole thing falls apart. Take $(10 - 5) - 2$. That equals $3$. But if you move the grouping to $10 - (5 - 2)$, you get $10 - 3$, which is $7$. Not the same. Not even close. This is why we have to be incredibly careful with the order of operations (PEMDAS) when we aren't dealing with simple addition or multiplication.

Why Does This Matter in 2026?

You might think that knowing how to define the associative property is just for passing a 6th-grade quiz, but it’s actually the secret sauce in modern computing.

In the world of big data and cloud computing, we use something called "parallel processing." Imagine you have a billion numbers to add up. A single computer would take a long time to do that linearly. However, because addition is associative, we can split that billion-number list into ten different groups of 100 million.

- Server A adds Group 1 and 2.

- Server B adds Group 3 and 4.

- Server C adds the results of A and B.

Because the property holds true, the final answer is guaranteed to be the same as if one person sat there for a year adding them one by one. If addition weren't associative, we couldn't do distributed computing. The internet as we know it would be significantly slower and less efficient.

Software engineers rely on this property when optimizing code. Compilers—the programs that translate human code into machine code—often rearrange operations to make them run faster on a specific processor. They can only do this safely if they know the operation is associative. If they tried to rearrange a non-associative operation, they’d introduce bugs that would crash your apps.

Real-World Examples Beyond the Classroom

Let's talk about building things. If you are a carpenter or a DIY enthusiast, you use these properties instinctively.

Suppose you’re building three identical shelves. Each shelf needs 4 long screws and 6 short screws. You could find the total number of screws for one shelf $(4 + 6 = 10)$ and then multiply by 3 shelves to get 30. Or, you could buy all the long screws first ($3 \times 4 = 12$) and all the short screws second ($3 \times 6 = 18$), then add them together $(12 + 18 = 30)$.

💡 You might also like: The Solar System Definition: Why It’s More Than Just Eight Planets and a Sun

The associative property (paired with the distributive property) ensures that your hardware store run doesn't result in a shortage of supplies. It's a mental safety net.

In accounting and finance, the associative property is why your balance sheet should work regardless of which sub-accounts you reconcile first. If you sum up your quarterly expenses by month and then total them for the year, you must arrive at the same number as if you summed up all categories (like rent, utilities, payroll) across the entire year first. If those numbers don't match, you haven't broken math; you've made an entry error.

The Cognitive Load Factor

Humans actually use the associative property to reduce "cognitive load." That’s a fancy way of saying we group numbers to make them easier to handle in our heads.

If someone asks you to add $17 + 8 + 2$ in your head, you probably don't do $17 + 8 = 25$, then $25 + 2 = 27$. Most people instinctively group the $8 + 2$ first because it makes a "clean" 10. Then they add $17 + 10$ to get $27$. You just used the associative property to make yourself faster than a calculator. You redefined the grouping to find a "compatible number."

Scientific Context: Linear Algebra and Beyond

If we look at higher-level mathematics, like linear algebra, the associative property becomes even more critical. Matrix multiplication is associative. This is a massive deal in 3D graphics and game development.

When you’re playing a game like Cyberpunk 2077 or Fortnite, the computer is constantly multiplying matrices to rotate, scale, and move 3D objects on your screen. Because matrix multiplication is associative, the computer can pre-calculate certain transformations, saving thousands of calculations per second. Without this mathematical "loophole," your frame rate would drop to zero.

However, mathematicians also study structures where the associative property doesn't work. These are called "non-associative algebras." An example is the Octonions. While most of us will never touch an Octonion in our daily lives, they are used in high-level physics and string theory. It goes to show that while associativity feels like a "given," it's actually a specific, beautiful feature of the numbers we use to build our world.

How to Explain This to a Kid (Or Your Boss)

If you need to explain this quickly, forget the variables. Use physical objects.

Grab three piles of rocks.

- Pile A: 2 rocks

- Pile B: 3 rocks

- Pile C: 4 rocks

Show them that pushing Pile A and Pile B together first, then adding Pile C, results in the same big pile as pushing Pile B and Pile C together first, then adding Pile A. It is a visual, tactile proof that the grouping—the "association"—is irrelevant to the outcome.

Actionable Insights for Daily Use

Understanding the associative property isn't just about trivia; it's about efficiency.

- Mental Math Hack: When adding or multiplying a string of numbers, always look for "anchors" or "friendly numbers." If you see a $5$ and a $2$, group them to make a $10$ immediately. Use the associative property to bypass the left-to-right slog.

- Debugging Logic: If you’re working in Excel or writing a basic script and your totals are wrong, check your non-associative operations (subtraction and division). You likely have a grouping error where you assumed the order didn't matter, but it very much did.

- Teaching Tip: When helping kids with homework, don't just give them the definition. Ask them to find three ways to group a string of four numbers. Let them prove to themselves that the answer doesn't change. This builds "number sense" rather than just rote memorization.

The associative property is a foundational pillar. It provides the consistency needed for everything from basic commerce to the algorithms that power AI. It’s one of the few things in life that is actually, reliably, 100% predictable.

Next Steps for Mastery

To truly master these concepts, try applying the associative property to mental multiplication. Next time you have to calculate something like $12 \times 25$, think of it as $(3 \times 4) \times 25$. Then, shift the association to $3 \times (4 \times 25)$. Suddenly, you're just multiplying $3 \times 100$. This kind of "mathematical flexibility" is exactly what separates people who are "good at math" from people who just memorize formulas. Start looking for those groups of 10, 100, or 1000 in every string of numbers you encounter, and watch how much faster your brain processes the world around you.