Back in 2014, the world of computer vision was hitting a brick wall. It was a weird, frustrating plateau. Everyone knew that "deeper is better"—if a neural network with 10 layers worked well, one with 20 layers should theoretically be a godsend. But it wasn't. Researchers were finding that as they stacked more layers onto their models, the accuracy didn't just level off; it plummeted. This wasn't because of overfitting, which is what most people initially assumed. It was a much nastier problem called the vanishing gradient. Basically, as you tried to train these massive stacks of math, the signal used to update the weights would get smaller and smaller as it traveled backward through the layers until it effectively disappeared. The network stopped learning. It just sat there.

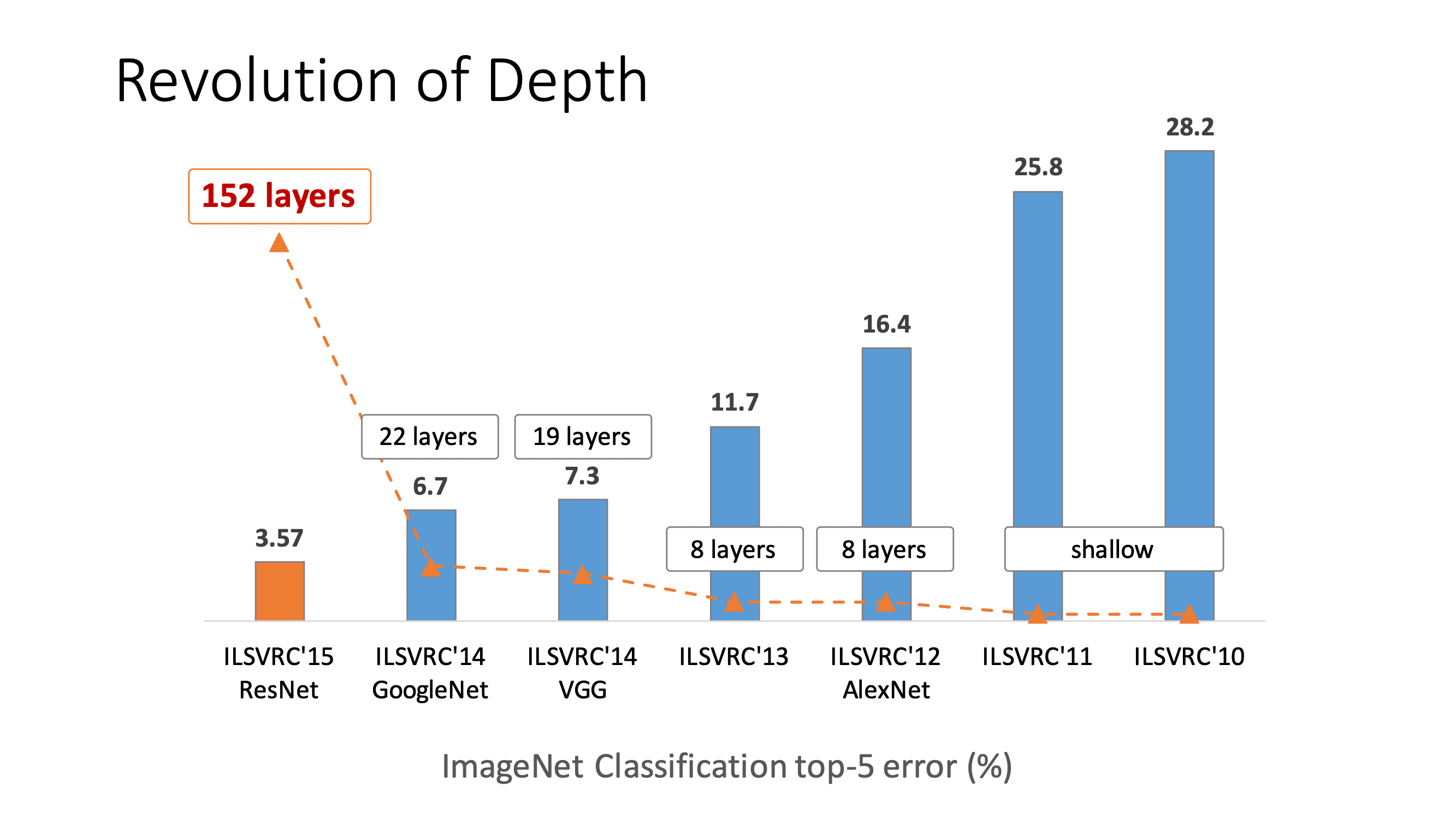

Then came the 2015 ILSVRC competition. A team from Microsoft Research—Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun—introduced the world to deep residual learning for image recognition. They didn't just win; they absolutely crushed it. Their model, ResNet, had 152 layers. That was roughly eight times deeper than VGG nets, which were the reigning heavyweights at the time. How did they do it without the whole thing collapsing? They added a "shortcut."

The problem with being too deep

We used to think that adding layers was a linear path to intelligence. If you have a network trying to identify a cat, the first few layers might find edges. The middle layers find shapes like ears or whiskers. The final layers understand "cat-ness." But when you get to 50 or 100 layers, the optimization becomes a nightmare.

In a standard "plain" network, each layer is expected to learn a completely new representation of the data. If the layer fails to learn something useful, it garbles the signal. Imagine playing a game of "Telephone" with 100 people. By the time the message gets to the end, it's total gibberish. This is exactly what was happening in deep neural networks before deep residual learning for image recognition fixed the logic. The researchers noticed that even if you just took a shallow, working network and added "identity" layers—layers that do absolutely nothing and just pass the input through—the deeper model still performed worse than the shallow one. That’s insane. It means our optimization algorithms (like stochastic gradient descent) were struggling to even learn how to do nothing.

How the residual block actually works

The genius of ResNet is the "skip connection" or "shortcut connection." Instead of forcing every layer to learn the entire mapping from point A to point B, the authors decided to let the layers learn the difference—the residual.

📖 Related: Longitude Explained: Why These Invisible Lines Still Run Our World

Let’s get a bit technical but keep it real. If the desired underlying mapping is $H(x)$, we let the stacked non-linear layers fit another mapping of $F(x) := H(x) - x$. The original mapping is then recast into $F(x) + x$. It sounds like a tiny mathematical tweak. It isn't. It's a fundamental shift in how we think about information flow. By adding that $+ x$ at the end of a block, you are essentially saying, "Hey, if these layers don't find anything useful to add, they can just learn to be zero." If the layers are zero, the signal $x$ just passes through untouched.

This makes it incredibly easy for the network to preserve information across hundreds of layers. You’ve probably seen diagrams of these "bottleneck" blocks. In deeper versions of ResNet, like ResNet-101 or ResNet-152, they use a three-layer stack of $1 \times 1$, $3 \times 3$, and $1 \times 1$ convolutions. The $1 \times 1$ layers are there to reduce and then restore dimensions. This keeps the computational load from exploding while still giving the network the depth it needs to understand complex patterns.

It’s not just about depth

People talk about ResNet like it's just about being "long." It’s actually about the loss landscape. If you visualize the "terrain" that an optimizer has to navigate to find the best settings for a network, a standard deep network looks like a jagged, messy mountain range with tons of false peaks and dead ends. ResNet flattens that terrain. It makes the "bowl" smoother.

A 2018 paper by Li et al., "Visualizing the Loss Landscape of Neural Nets," proved this visually. They showed that skip connections prevent the transition from a smooth convex-like surface to a chaotic one. That’s why you can train a ResNet-101 in less time and with more stability than a much smaller plain network.

Real-world impact and why you still use it

You might think that in the era of Vision Transformers (ViTs) and Attention mechanisms, deep residual learning for image recognition is old news. You'd be wrong.

ResNets are the "workhorse" of the industry. If you’re building a production system today—say, a facial recognition door lock or a medical imaging tool for spotting tumors—you probably start with a ResNet backbone. Why? Because they are predictable. They are fast on hardware. Almost every edge computing chip, from the ones in your phone to the industrial ones in a Tesla, is optimized specifically to run these kinds of convolutional residual blocks.

- Medical Imaging: ResNet-50 is the gold standard baseline for detecting anomalies in X-rays.

- Satellite Imagery: Companies like Maxar use residual architectures to process terabytes of data to track deforestation.

- Object Detection: Frameworks like Faster R-CNN or Mask R-CNN almost always use a ResNet or a ResNeXt (a beefed-up version) as the "feature extractor."

There’s also the concept of "transfer learning." Because the original ResNet was trained on the massive ImageNet dataset, it already "knows" what the world looks like. You can take a pre-trained ResNet, chop off the last layer, and train it on your specific data—like identifying different types of rare succulents—and it will work with very little data. That’s the power of the residual revolution.

✨ Don't miss: Who Made the Cotton Gin: The Messy Truth Behind Eli Whitney’s Invention

What most people get wrong about ResNet

A common misconception is that ResNets are just very deep versions of the VGG network. Honestly, that’s an oversimplification. VGG relies on brute force. ResNet relies on an architectural trick that essentially allows it to behave like an ensemble of many shorter networks.

Think about it: with all those skip connections, there are millions of possible paths for data to flow through the network. Some paths are short, some are long. This means a ResNet is kinda like a huge collection of networks of different lengths all working together. This "implicit ensemble" effect is likely why it generalizes so well to data it has never seen before.

Another mistake? Assuming more layers always equals more better. While ResNet-152 is powerful, ResNet-50 is often the "sweet spot" for most developers. It offers a great balance between accuracy and inference speed. If you’re running a model on a drone, you don't want the 152-layer beast; it’ll drain the battery and lag. You want the efficiency of a smaller residual stack.

The limitations (nothing is perfect)

Even with its brilliance, deep residual learning for image recognition isn't magic. It still struggles with global context. Because it uses convolutions, it’s very good at looking at local pixels and their immediate neighbors. But it has a harder time understanding the relationship between a pixel in the top-left corner and one in the bottom-right.

This is where Transformers have started to take over in some high-end research. Transformers use "Self-Attention" to look at the whole image at once. However, even these modern giants often incorporate residual connections. The "Res" in ResNet has become a permanent fixture in deep learning architecture, even outside of image recognition. If you look at the code for GPT-4 or any Large Language Model, you’ll find residual connections there too. Kaiming He’s team didn't just fix image recognition; they changed the blueprint for all of AI.

How to use this in your projects

If you are actually looking to implement this, don't try to build the architecture from scratch unless you're a student trying to learn the math. Use the libraries.

- PyTorch/TensorFlow: Both have

torchvision.modelsortf.keras.applicationswhere you can load a ResNet with one line of code. - Freeze the Base: When starting, freeze the weights of the early layers. These layers have already learned how to see edges and textures. Only train the "head" of the network for your specific task.

- Check your dimensions: One of the most common errors when building custom residual blocks is a dimension mismatch. Remember that the skip connection $x$ must be the same size as the output $F(x)$ for them to be added together. If you change the stride or the number of filters, you need to apply a $1 \times 1$ convolution to the skip connection to make it match.

- Watch the Batch Norm: ResNets rely heavily on Batch Normalization. If you use a batch size that is too small (like 1 or 2), the model won't train properly. Stick to at least 16 per GPU if you can.

The move toward deep residual learning for image recognition was the moment AI stopped being a "shallow" toy and started becoming a "deep" tool that actually works in the messy, real world. It turned the "vanishing gradient" from a brick wall into a minor speed bump. Whether you're a developer, a researcher, or just someone curious about why your phone can suddenly recognize your cat's face in the dark, you have ResNets to thank for that.

Next Steps for Implementation

💡 You might also like: Why 0 Divided by -6 Is Actually Simple (And Why We Overthink It)

To put this into practice, start by pulling a pre-trained ResNet-50 from a library like PyTorch and run it against a small, custom dataset (even just 100 images of two different objects). Observe how the "residual" nature allows the model to converge much faster than a simple CNN. Once you have a baseline, experiment with "Fine-tuning" by unfreezing the last two residual blocks to see how much accuracy you can squeeze out of the architecture for your specific use case.