Ever watched a log rot in the woods? Or maybe you’ve seen the way a fizzy soda goes flat if you leave it out too long. It feels like things are just disappearing. They aren't. Not even close. You’re actually witnessing a decomposition reaction in real-time, which is basically the universe's way of hitting the "reset" button on complex molecules.

Everything around us is built of clusters. Atoms holding onto other atoms. But those bonds aren't always permanent. Sometimes, you add a little heat, a jolt of electricity, or even just a specific enzyme, and the whole structure snaps. It’s like taking a Lego castle and ripping it back down into individual bricks. Without this specific chemical process, life would literally stall out. We’d be buried under a mountain of old organic matter, and your car’s airbag wouldn't work when you need it most.

The Core Mechanics of a Decomposition Reaction

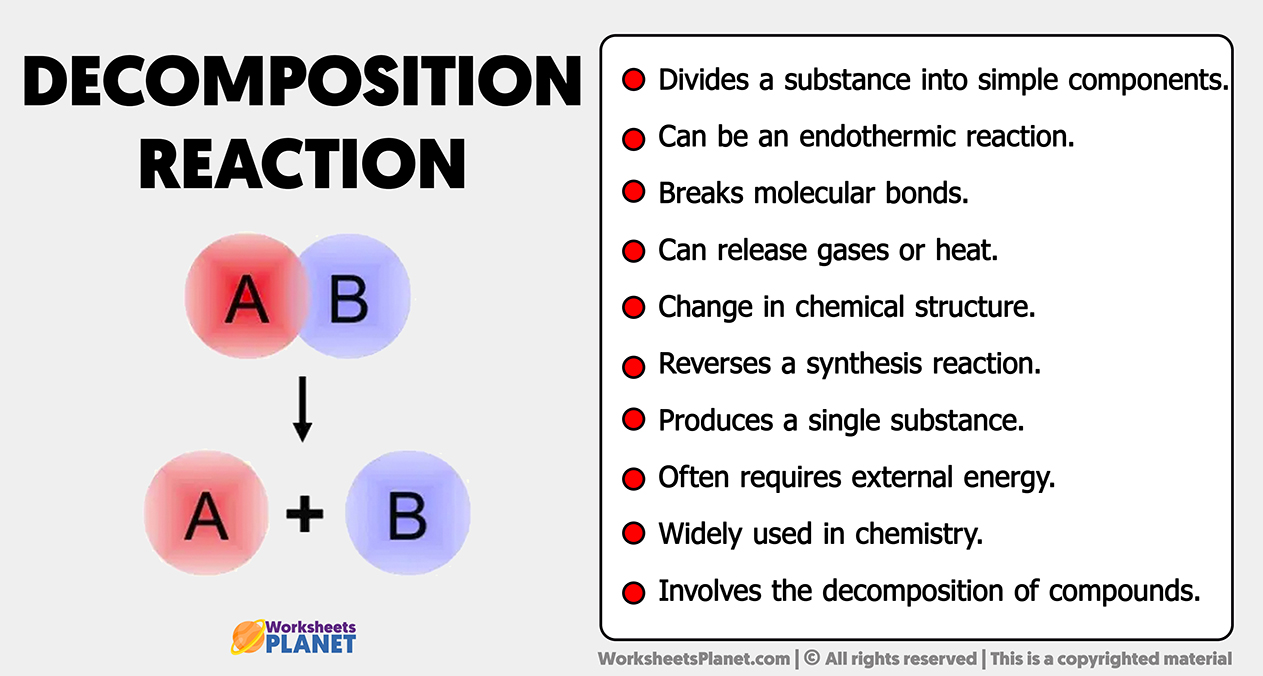

At its most basic, a decomposition reaction occurs when one single compound breaks down into two or more simpler substances. If you want the "textbook" version, it looks like $AB \rightarrow A + B$. But chemistry is rarely that clean or polite. It’s usually messy.

Think of it as the opposite of a synthesis reaction. In synthesis, you’re building. In decomposition, you’re dismantling. To get that dismantling started, you almost always need an energy input. Molecules are surprisingly stubborn; they don't just fall apart because they feel like it. You have to push them. This energy usually comes in the form of heat (thermal decomposition), light (photolysis), or electricity (electrolysis).

Take water, for instance. You can leave a glass of water on your counter for a thousand years and it will stay $H_2O$. But, if you run an electric current through it—a process called electrolysis—the bonds can't hold. The oxygen goes one way, the hydrogen goes the other. Suddenly, you have two gases instead of one liquid.

Why Heat Is the Usual Suspect

Most people encounter decomposition reactions through heat. This is thermal decomposition. You see it in your kitchen and in heavy industry. Calcium carbonate ($CaCO_3$), which is basically limestone, is a classic example. If you crank the heat up to about 825°C, it gives up. It splits into calcium oxide (quicklime) and carbon dioxide gas.

This specific reaction is the backbone of the cement industry. We wouldn't have skyscrapers without it. But it's also a massive source of carbon emissions. That’s the nuance of chemistry—the same reaction that builds our cities also alters our atmosphere.

Mercury(II) Oxide: The Experiment That Changed Everything

In the 1770s, Joseph Priestley (and independently, Carl Wilhelm Scheele) played around with a red powder called mercury(II) oxide. When he focused sunlight on it using a giant lens, the powder turned into liquid silver mercury and released a gas.

Priestley didn't know it yet, but he had just discovered oxygen. By forcing a decomposition reaction, he fundamentally changed how we understand the air we breathe. It wasn't "magic" making the candle burn brighter in his test tube; it was the liberated oxygen atoms that had been trapped inside the solid powder.

The Airbag: A Reaction That Saves Your Life

Here is a weird one. Sodium azide ($NaN_3$).

It’s a stable solid. You can drop it, and usually, nothing happens. But when your car’s sensors detect a massive, sudden deceleration (a crash), they send an electrical impulse to a small heating element. In a fraction of a second—about 30 milliseconds—the sodium azide undergoes a violent decomposition reaction.

👉 See also: Why the International Plaza Apple Store Still Sets the Standard for Tampa Tech

It turns into sodium metal and nitrogen gas.

The nitrogen gas is what inflates the bag. It happens so fast that the bag is full before your head even moves an inch toward the dashboard. It’s a literal explosion of decomposition. If that reaction was even slightly slower, it would be useless. The precision of chemical kinetics is the difference between a bruise and a tragedy.

Electrolysis and the Future of Energy

We hear a lot about the "Hydrogen Economy." Basically, the idea is that we can use hydrogen as a clean fuel. But hydrogen doesn't just hang out in pure form on Earth; it’s usually stuck to oxygen in water.

This is where the decomposition reaction becomes a technological holy grail. If we use solar or wind power to provide the electricity for electrolysis, we can "decompose" water into green hydrogen.

- Input: $H_2O$ + Electricity

- Output: $H_2$ (Fuel) + $O_2$ (Breathable air)

The problem? It’s currently expensive. Breaking those bonds takes a lot of juice. Scientists like those at MIT or the Max Planck Institute are constantly hunting for catalysts—substances that make the decomposition happen with less energy. If they crack that code, we change the world's energy grid forever.

Decomposition in Biology (The Gross Part)

We can't talk about things falling apart without talking about rot. When an organism dies, the complex proteins, fats, and carbohydrates that make up its body start to fail.

This isn't just "rotting." It’s a series of enzyme-driven decomposition reactions. Bacteria and fungi secrete enzymes that act like chemical scissors. They snip long protein chains into amino acids. They turn complex sugars into CO2 and water.

Honestly, it’s a beautiful cycle. If these reactions stopped, the nutrients would stay locked in the dead matter. New plants couldn't grow. The earth would run out of "building blocks" within a few generations. Your compost bin is essentially a high-speed decomposition reactor. You're managing the temperature and moisture to make sure those chemical bonds break down efficiently.

Photolysis: When Light Does the Heavy Lifting

Ever wonder why some medicines come in dark brown glass bottles? It's not for aesthetics.

Many chemicals are sensitive to photons. Silver chloride, for example, is very susceptible to light. If you expose it to the sun, it undergoes a decomposition reaction into silver metal and chlorine gas. This is the fundamental principle behind old-school film photography.

When you clicked the shutter, light hit the film, causing a tiny decomposition reaction that "recorded" the image in silver atoms. In medicine, light can decompose the active ingredients in your pills, turning them into something useless or even toxic. Hydrogen peroxide ($H_2O_2$) is another big one. In a clear bottle, light will turn it into plain old water and oxygen gas. You’d be pouring "water" on your cut, wondering why it isn't bubbling.

Misconceptions About These Reactions

A lot of people think decomposition is always "bad" because it implies things are breaking or spoiling. That’s a narrow view.

Sometimes, we need things to break. Think about digestion. When you eat a steak, your stomach acid and enzymes are forcing a decomposition reaction on those proteins so your body can actually absorb the nutrients. You are a walking, talking decomposition chamber.

📖 Related: When Was Chat GPT Launched: The Day the Internet Changed Forever

Another mistake is thinking that these reactions always happen on their own. As I mentioned earlier, most require an "activation energy." You can have a pile of wood (cellulose) sitting in a dry room for a century. It won't decompose until you provide the initial "spark" (heat) to start the oxidation/decomposition process.

Catalysts: The Secret Shortcut

Sometimes you don't want to use 800 degrees of heat. It's dangerous and expensive.

That’s where catalysts come in. A catalyst is a substance that speeds up a decomposition reaction without being used up itself. Manganese dioxide ($MnO_2$) is the classic classroom example. If you add it to hydrogen peroxide, the liquid turns into a fountain of steam and oxygen instantly.

The catalyst provides an alternative "pathway" for the reaction that requires much less energy. In your body, these are called enzymes. Without them, the chemical reactions required for you to think, move, and breathe would happen so slowly that you'd be dead before you could blink.

Summary of Reaction Types

| Type | Energy Source | Common Example |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal | Heat | Baking soda releasing CO2 in a cake |

| Electrolytic | Electricity | Splitting salt (NaCl) into sodium and chlorine |

| Photochemical | Light | Photosynthesis (the reverse) or film exposure |

| Biological | Enzymes | Digestion and composting |

What You Should Do Next

Understanding how things break down gives you a massive advantage in everyday life. If you want to apply this knowledge, start with these practical steps:

Check your medicine cabinet. Look for bottles that are opaque or dark. This is a sign that the contents are prone to photolysis. Store them in a cool, dark place to prevent a decomposition reaction from ruining your expensive prescriptions.

Master your compost. If your compost pile smells like rotten eggs, it's not decomposing "cleanly." It means it's gone anaerobic. Flip the pile to introduce oxygen, which changes the chemical pathway of the decomposition and helps it break down faster into nutrient-rich soil.

Understand your "fizz." Next time you open a soda, look at the bubbles. That’s carbonic acid ($H_2CO_3$) decomposing into water and carbon dioxide gas. It’s a simple, harmless reaction that happens the moment the pressure is released.

👉 See also: Belkin BoostCharge Pro: What Most People Get Wrong About These High-End Chargers

Observe the world through bonds. Next time you see rust, a rotting log, or a battery charging, ask yourself: "Is something being built here, or is it falling apart?" Nine times out of ten, it's a decomposition reaction doing the heavy lifting behind the scenes.

Chemistry isn't just about what you can make. It’s about understanding the inevitable reality that everything—at some point—is going to break down. Knowing how it happens is how we learn to build things that last.