It is pouring. You were told it would be sunny, yet here you are, standing under a bus stop awning with a useless pair of sunglasses. We’ve all been there. It feels like the people behind the screen are just throwing darts at a map. But honestly? We are living through a quiet revolution in how we understand the atmosphere. Decoding the weather machine isn't just a catchy phrase from a PBS Nova special; it is the literal, grit-teeth struggle of thousands of scientists trying to turn the chaos of the sky into math that actually makes sense.

The atmosphere is a beast. It’s a fluid, swirling, chaotic mess of heat, moisture, and pressure. Predicting what it will do next week is like trying to guess the exact shape of a ripple in a bathtub ten minutes after you’ve splashed the water. Yet, we’re getting scarily good at it.

💡 You might also like: Xfinity Outage Augusta GA: Why Your Internet Keeps Dropping and How to Fix It

The Math Behind the Clouds

Most people think weather forecasting is about looking at a satellite image and seeing where the big white blobs are moving. That’s a tiny part of it. The real work happens in massive data centers where supercomputers crunch equations that would make a PhD physicist weep. These are the Navier-Stokes equations. They describe how fluids move.

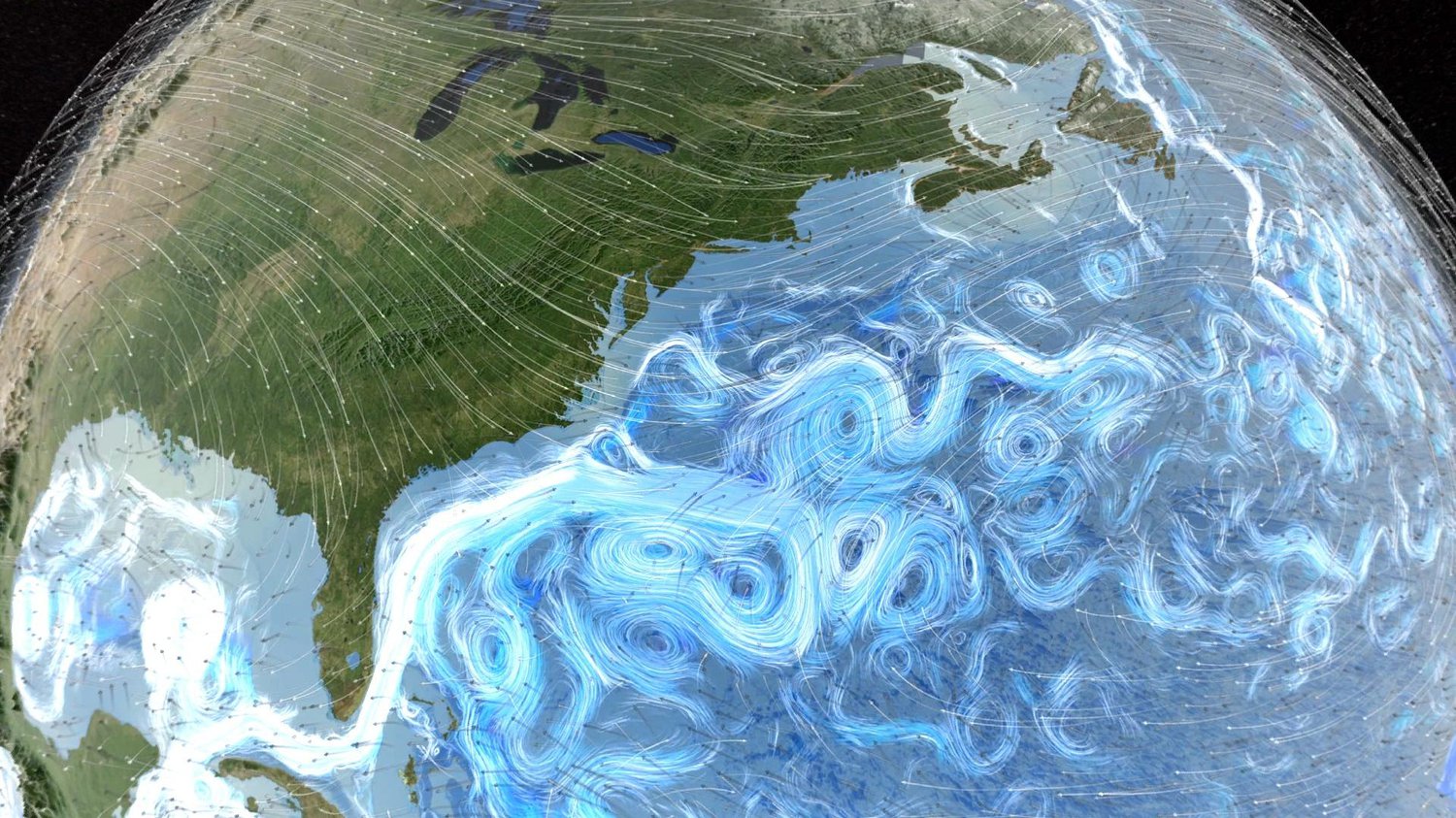

Basically, the "weather machine" is a global grid. Imagine the entire Earth covered in a mesh of boxes. Inside every box, the computer calculates temperature, wind speed, humidity, and pressure. Then it looks at how those boxes affect their neighbors.

The problem? The grid used to be too big. If your grid boxes are 50 miles wide, the computer "misses" a thunderstorm that is only 5 miles wide. It just falls through the cracks. This is why older forecasts were so hit-or-miss. Today, thanks to massive leaps in computing power from companies like NVIDIA and IBM, those grid boxes are shrinking. We are seeing the atmosphere in high-definition for the first time.

Why the "Butterfly Effect" is Real

You've heard the cliché: a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil and causes a tornado in Texas. It’s a bit dramatic, but the math holds up. In technical terms, it’s called "sensitive dependence on initial conditions."

If your starting data is off by even 0.1%, your seven-day forecast is garbage. This is why scientists are obsessed with "data assimilation." They are shoving every possible bit of info into the machine—sensor data from commercial airplanes, buoy readings in the middle of the Pacific, and even signals from GPS satellites that warp slightly as they pass through moisture in the air.

The New Players: AI and Machine Learning

Here is where things get weird. For fifty years, we used physics-based models. We told the computer the rules of gravity, heat, and friction, and let it simulate the world. But now, we have AI models like Google’s GraphCast and Huawei’s Pangu-Weather.

These don’t actually "know" physics in the traditional sense. Instead, they’ve looked at 40 years of historical weather data and learned the patterns. It’s like a seasoned farmer who knows it’s going to rain because the air "feels" a certain way, but on a global, hyper-digital scale.

- Speed: Traditional models take hours to run on supercomputers. AI can do it in seconds on a laptop.

- Accuracy: In many tests, these AI models are now outperforming the gold-standard European model (ECMWF) for medium-range forecasts.

- The Catch: AI struggles with "black swan" events—extreme weather that has never happened before. Because it learns from the past, it might not see a future that looks different due to a changing climate.

The Human Element in the Machine

We shouldn't ignore the meteorologists. You might think they just read the teleprompter, but the pros at the National Weather Service (NWS) do something called "forecasted uncertainty."

They don't just run the model once. They run it 50 times with slightly different starting points. This is an "ensemble forecast." If 45 of those runs show a blizzard, they tell you to buy bread and milk. If only 10 show it, they mention a "chance of flurries." Decoding the weather machine requires a human to look at those 50 possibilities and say, "I've seen this setup before; the models are overestimating the moisture."

Dr. Marshall Shepherd, a leading expert and former president of the American Meteorological Society, often points out that people confuse "weather" (what’s happening now) with "climate" (the stats of the atmosphere over time). The machine has to handle both. It’s trying to predict a single raindrop while also accounting for the fact that the entire ocean is getting warmer, which adds more fuel to the engine.

👉 See also: Why the Face of the Moon Looks Different Every Time You Look Up

The Reality of Severe Weather

Let's talk about the scary stuff. Tornadoes. Even with our best tech, the lead time for a tornado warning is only about 13 to 15 minutes. That’s not much.

The reason is that a tornado is a micro-event. The "weather machine" can tell us that the conditions in Oklahoma are "primed" for a rotation, but it can’t always tell us exactly which cloud will drop a funnel. We are currently testing "Warn-on-Forecast" systems that use high-resolution radar data to try and push that lead time to 30 or even 60 minutes. It would save hundreds of lives every year.

Decoding the Future

Is the weather machine ever going to be perfect? No. Chaos theory says it’s impossible. We will likely never have a perfectly accurate 30-day forecast because there are too many variables in the universe.

However, the leap from a 3-day forecast to a 7-day forecast over the last few decades is one of the greatest scientific achievements in human history. We’ve basically added one day of accuracy every decade. Today’s 5-day forecast is as accurate as a 1-day forecast was in 1980. That is insane when you think about it.

What You Should Do With This Information

Stop relying on the generic "sun or cloud" icon on your phone's default app. Those are often automated and don't include the human nuance we talked about.

- Use the "Forecast Discussion": Go to weather.gov and search for your zip code. Scroll down to "Forecast Discussion." This is where the actual meteorologists write out their thought process. They’ll say things like, "The models are disagreeing, but we think the cold front will stall." It’s the raw data behind the icons.

- Look at the Probability of Precipitation (PoP): A 40% chance of rain doesn't mean it will rain in 40% of the area. It means there is a 40% chance that at least a measurable amount of rain will fall at any given point in the forecast area. Subtle difference, big impact.

- Check Multiple Models: Apps like Windy or Weather Underground let you toggle between the American (GFS) and European (ECMWF) models. If they both agree, you can be pretty confident. If they don't, grab an umbrella just in case.

- Support Local News: Local meteorologists know the "micro-climates" of your city—like how a certain hill blocks the wind or how the lake increases snowfall. The global "machine" often misses those local quirks.

Decoding the weather machine is an ongoing project. It’s a mix of satellites screaming through space, AI whispering patterns, and humans trying to make sense of the wind. We’re getting there, one grid box at a time.