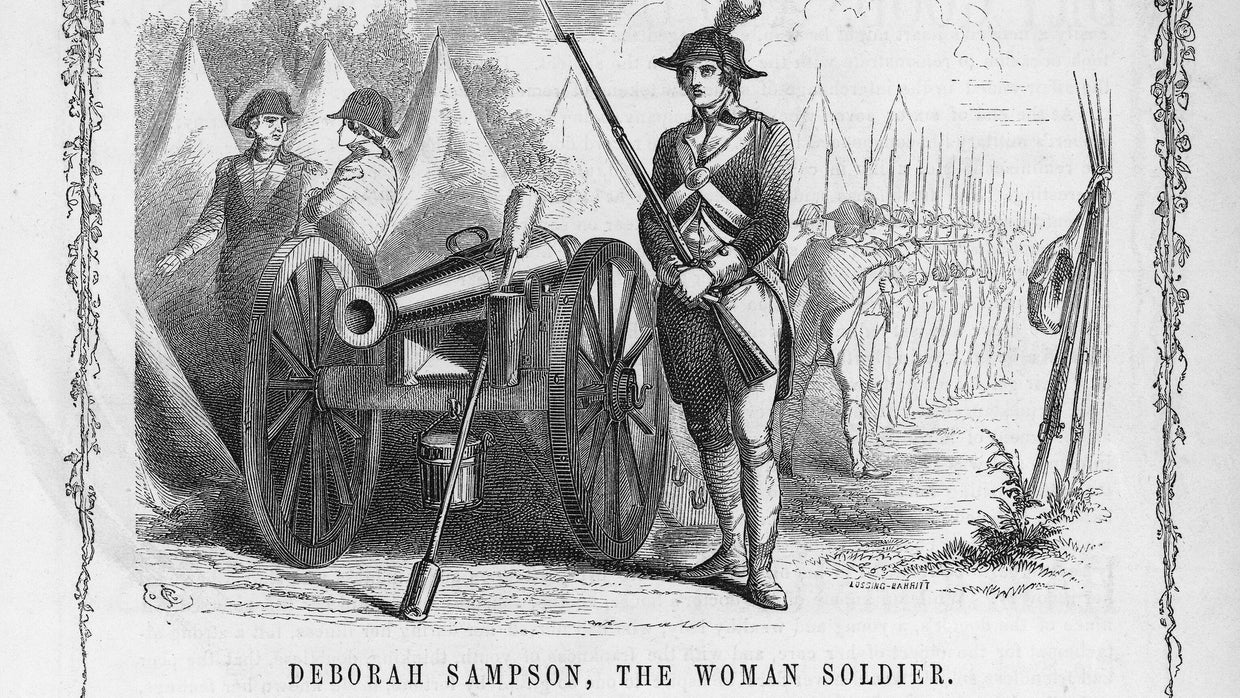

Imagine being twenty-one, standing in a dusty recruitment line in Worcester, Massachusetts, and hoping like hell the guy with the ledger doesn't look too closely at your jawline. That was Deborah Sampson in May 1782. Most people know the "Disney version" of this story—girl wants to fight, puts on a hat, becomes a war hero. But honestly, the real Deborah Sampson American Revolutionary War experience was way grittier, more desperate, and frankly, a bit more legally complicated than the history books usually let on.

She wasn't just a "patriot." She was broke.

Sampson was a former indentured servant who had basically aged out of her contract with nothing to show for it but calloused hands and a self-taught education. She spent a couple of years teaching school and weaving, but the pay was garbage. In 1782, the Continental Army was offering bounty money for enlistment. For someone like Deborah, that money wasn't just a bonus; it was a lifeline.

The "Robert Shurtleff" Masquerade

Her first attempt at enlisting was actually a total disaster. She dressed up, called herself Timothy Thayer, signed the papers, and then immediately went to a local tavern to celebrate. Someone recognized her. She had to give the bounty money back and was basically kicked out of her Baptist church for "unnatural" behavior.

You'd think she’d quit there. She didn't.

She just walked to a different town, Bellingham, and tried again. This time, she became Robert Shurtleff. She was tall for the time—about 5'7"—and had a plain, strong face that helped her blend in with the teenage boys who filled the ranks. She joined the Light Infantry Company of the 4th Massachusetts Regiment. This wasn't some cushy rear-guard job. These were the elite scouts. They did the dirty work: skirmishing, recon, and hand-to-hand combat in the "Neutral Ground" of Westchester County, New York.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Life in the Neutral Ground

The Neutral Ground was basically a lawless no-man's-land between British-occupied New York City and the American lines further north. It was crawling with "Cowboys" and "Skinners"—loyalist and rebel guerrillas who spent more time robbing civilians than actual fighting. Sampson was right in the thick of it.

During a skirmish near Tarrytown, she took a sword slash to the forehead and two musket balls to the thigh.

This is where the story gets intense. She let the doctors treat her head, but she absolutely refused to let them touch her leg. Why? Because a leg wound meant taking off your breeches. To keep her secret, she crawled away, pulled out a penknife and a sewing needle, and dug one of the musket balls out of her own flesh.

She couldn't get the second one. It stayed in her leg for the rest of her life.

The Philadelphia Fever and the Big Reveal

The war was winding down by 1783, but Sampson was still in uniform. She was serving as an orderly to General John Paterson in Philadelphia when an epidemic hit. She went down hard. Unconscious. Near death.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

When Dr. Barnabas Binney reached inside her shirt to check her heartbeat, the game was up.

But here’s the cool part: Binney didn't rat her out. Not immediately, anyway. He took her to his own house to recover, and once she was healthy, he sent her back to the army with a letter for General Paterson. On October 25, 1783, she received an honorable discharge. No court-martial. No public shaming. Just a "thanks for your service" and a ticket home.

The Battle After the War

If you think life got easy for her after she hung up the musket, you've got another thing coming. She went back to Massachusetts, married a farmer named Benjamin Gannett, and had three kids. They were poor. Like, "borrowing ten dollars from neighbors" poor.

Sampson spent the next twenty years fighting a different kind of war: the bureaucracy of the U.S. government.

Why Paul Revere Stepped In

By 1804, Deborah was in bad shape. Those old war wounds made it hard for her to work the farm. She started a lecture tour—the first woman in America to do so—where she’d go on stage in her old uniform and perform the manual of arms (military drills). People loved the spectacle, but it didn't pay the bills.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Enter Paul Revere.

The famous silversmith lived nearby in Canton and became an unlikely advocate for her. He wrote to Congress, basically saying, "Look, I’ve met her. She’s a hardworking woman, her health is trashed from the war, and she deserves the same pension as any man."

Thanks to Revere's political weight, she finally got her federal pension in 1805. She was one of the first women to ever receive one for her own military service.

What We Can Learn from Deborah Sampson

Deborah Sampson’s story isn't just a "girl power" anecdote from the 1700s. It’s a messy, human story about economic survival and the sheer grit it took to navigate a world that had no place for a woman who didn't want to stay in the kitchen.

If you're looking to dive deeper into this history, here’s how you can actually engage with her legacy today:

- Visit Sharon, Massachusetts: You can see her statue at the public library and visit her grave at Rock Ridge Cemetery. It’s a quiet spot, but it feels heavy with history.

- Read the Source Material: Check out The Female Review by Herman Mann. He was her first biographer. Just a heads up: he embellished a lot to make the book sell, so take his "flowery" descriptions with a grain of salt.

- Check Out the Deborah Sampson Act: In 2021, a law was passed in her name to improve healthcare for women veterans. It’s a reminder that the "Robert Shurtleffs" of today are still fighting for the recognition Deborah spent her life chasing.

Next time someone talks about the "Founding Fathers," remind them about the woman who dug a bullet out of her own leg just to keep her spot in the line. That's the real Deborah Sampson American Revolutionary War story. It wasn't pretty, it wasn't easy, but it was remarkably real.

Actionable Insight: If you're researching Revolutionary War ancestors or local history, don't just look for "Private" or "Sergeant" in the records. Look for the stories of those who served in the Light Infantry—the units that required the most physical stamina. You might find that the "young boys" listed in the muster rolls had much more complex identities than the ink on the page suggests.