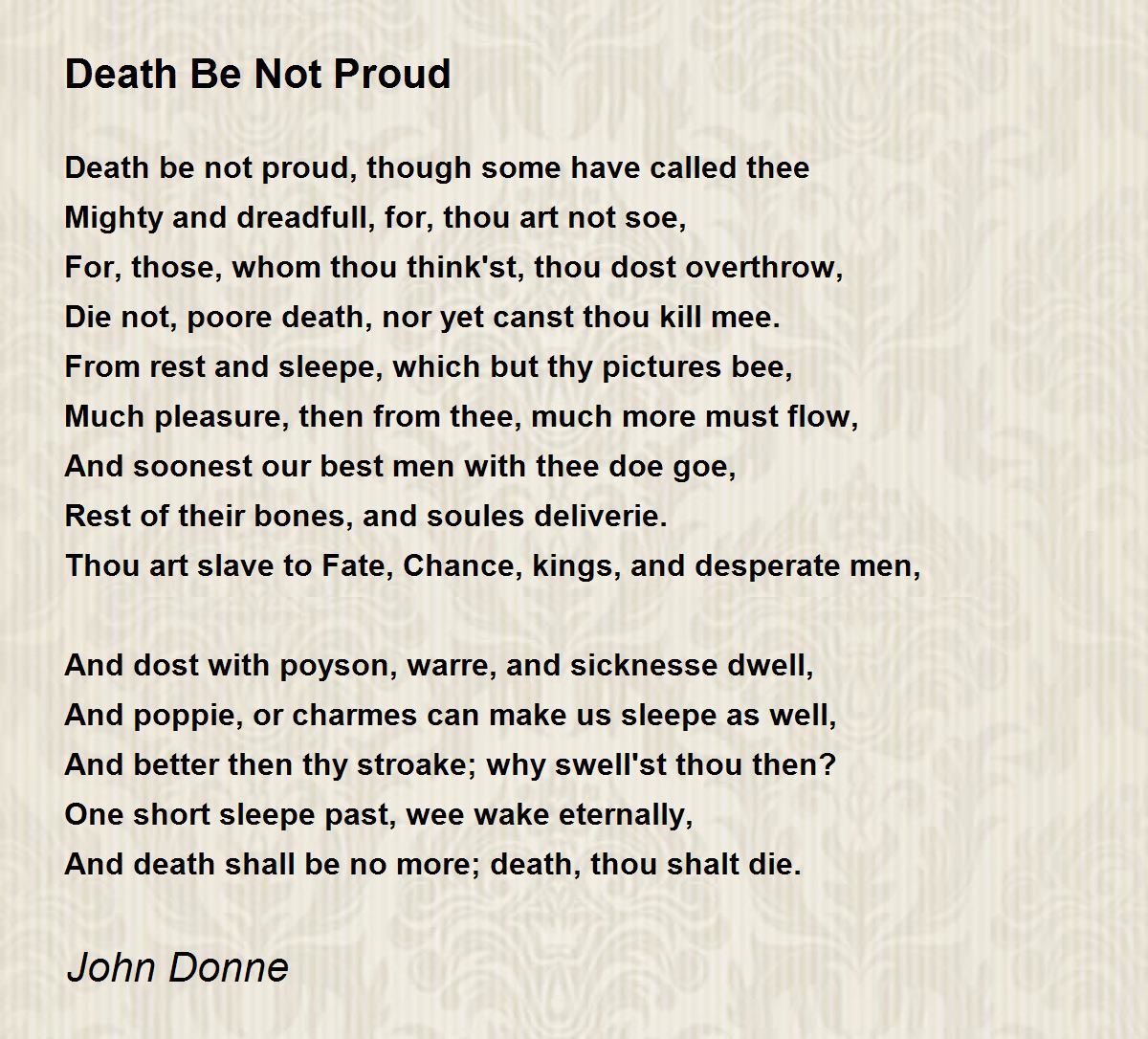

Death is usually the one thing we can’t talk back to. It’s the final word. The ultimate lights out. But about four hundred years ago, a guy named John Donne decided he wasn't having any of it. He sat down and wrote Death Be Not Proud, a poem that basically treats the Grim Reaper like a schoolyard bully who isn't nearly as tough as he thinks he is.

It’s bold. It’s kinda cocky.

Honestly, it’s one of the most famous pieces of literature in the English language for a reason. You’ve probably heard it at funerals or seen it quoted in movies, but most people sort of miss the psychological warfare Donne is actually playing here. He isn't just saying "don't be afraid." He’s saying Death is a "slave" to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men. He’s calling Death a loser.

The Weird History of Holy Sonnet X

Most people call it Death Be Not Proud, but its "official" name is Holy Sonnet X. Donne didn't even publish these while he was alive. Think about that for a second. One of the most influential poems in history was basically sitting in a private collection until 1633, two years after he died.

Donne’s life was a mess of contradictions. He started as a young, lusty poet writing about "going to bed" and ended up as the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. He was obsessed with mortality. He lived in a time when the plague was basically a permanent roommate in London. You couldn't walk down the street without seeing a reminder that life was fragile. So, when he writes this poem, he isn't speaking from some ivory tower. He’s speaking as a man who buried friends, family, and eventually prepared for his own end by posing for a portrait in a funeral shroud.

Why the Opening Line is a Total Power Move

"Death, be not proud, though some have called thee / Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so."

That is a heck of an opening. It’s a direct address—a literary device called an apostrophe. He’s talking to Death as if it’s a person standing in the room. By doing this, Donne immediately strips away the mystery. You can’t argue with a force of nature, but you can definitely argue with a person.

👉 See also: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The rhythm here is clunky on purpose. It’s a Petrarchan sonnet, but Donne messes with the meter. It feels like he’s poking his finger into Death’s chest. He tells Death that those it thinks it "overthrows" don't actually die. This is the core of his religious argument, sure, but even from a secular perspective, it’s a fascinating psychological reframe.

Breaking Down the "Slave" Argument

The middle of the poem is where Donne gets really disrespectful. He says:

"Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, / And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell."

This is the intellectual "gotcha" moment. If Death only shows up when "Fate" or a "King" (who orders an execution) tells it to, then Death isn't the boss. It’s just the executioner. It’s the delivery guy. It’s "dwelling" with things like poison and sickness—low-life company.

Donne even goes as far as to say that "poppy or charms" (basically drugs or magic spells) can make us sleep better than Death can. If a bit of opium can do a better job of giving us rest than the "Mighty" Death, then what does Death really have to brag about? It’s a total takedown of the ego of the afterlife.

The Problem of the Final Couplet

The poem ends with a paradox that has kept English majors awake at night for centuries: "One short sleep past, we wake eternally / And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die."

✨ Don't miss: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Wait. How does Death die?

In Donne’s Christian worldview, the "death of Death" happens through the resurrection. But even if you aren't religious, the logic is sound within the poem's universe: if Death’s entire job is to transition people from one state to another, and that transition eventually ends, then Death is out of a job. It ceases to exist.

Why We Still Care (Even in 2026)

We live in an age of bio-hacking and longevity research. We are still trying to beat Death, just with science instead of sonnets. But the fear is the same. Death Be Not Proud works because it addresses the "dreadful" reputation of the end.

Scholar Helen Gardner once pointed out that Donne’s Holy Sonnets aren't just expressions of faith; they are expressions of a man struggling to have faith. That’s why the tone is so aggressive. He’s trying to convince himself as much as he’s trying to convince us. We like the poem because it’s a "fake it till you make it" anthem for the soul.

There's also the "Wit" factor. Donne was a Metaphysical poet. They loved "conceits"—which are just really elaborate, weird metaphors. Comparing death to a short nap is a classic Metaphysical move. It shrinks the scariest thing in the universe down to the size of a pillow.

Common Misconceptions About the Poem

A lot of people think this poem is just a happy, hopeful "see you in heaven" message. It’s really not. It’s actually quite dark and combative.

🔗 Read more: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

- It’s not a comfort poem. It’s an argument. Donne is litigating.

- The punctuation matters. Depending on which version of the 1633 manuscript you look at, the ending might have a comma or a semicolon, which changes whether the final line is a quiet realization or a shouted triumph.

- It isn't about ignoring death. It's about looking directly at it and refusing to be impressed.

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by the "bigness" of life’s problems, Donne’s approach is actually a pretty solid mental health hack. Take the thing that scares you and list all the reasons it’s actually dependent on other things. Demystify it. Mock it a little.

Actionable Takeaways for Reading (and Using) Donne

If you want to actually "get" this poem beyond just reading a summary, try these three things:

- Read it aloud, but change the tone. Read it once like a prayer, then read it once like you’re a lawyer in a courtroom. Notice how the meaning shifts when you treat Death like a defendant.

- Look for the "turn." In sonnets, there’s usually a "volta" or a turn. In Death Be Not Proud, it happens around line 9 ("Thou art slave to fate..."). See how the poem moves from general insults to specific accusations.

- Apply the "Donne Method" to a modern fear. Take something that stresses you out—climate change, AI taking your job, your taxes—and write a two-sentence "apostrophe" to it. Tell it why it’s not as "mighty" as it thinks it is.

Death Be Not Proud isn't just a relic of the 17th century. It’s a template for intellectual courage. It reminds us that while we might not be able to escape the physical reality of dying, we don't have to give the idea of death the satisfaction of our fear.

To dive deeper into this, look up the "Variorum" editions of Donne’s poetry. They show how different scholars have fought over every single comma for 400 years. It’s a rabbit hole, but it’s worth it. You should also check out the play Wit by Margaret Edson, which uses this specific sonnet as its emotional backbone. Seeing how a character facing a terminal illness uses Donne’s words to navigate their own mortality is perhaps the best "modern" commentary on the poem you’ll ever find.

Key Summary of Insights

- Context is King: Written during a time of plague, the poem is a defensive reaction to constant mortality.

- The Power of Personification: By treating Death as a person, Donne makes it vulnerable to criticism and logic.

- The "Slave" Argument: Death isn't an independent power; it’s a tool used by fate and human circumstance.

- The Eternal Wake-Up: The poem’s final logic relies on the idea that Death is a temporary transition, not a permanent end.

Donne's work teaches us that the way we frame our reality determines how much power that reality has over us. Death might be inevitable, but "proud" is a choice.