You’ve probably heard it. That slow, rolling melody that feels like a warm blanket on a Sunday morning. It’s a staple at British royal funerals and small-town weddings alike. But here is the thing about the Dear Lord and Father of Mankind hymn: it was never actually meant to be a hymn. Not even close. In fact, the man who wrote the words probably would have been pretty confused—maybe even a little annoyed—to see people singing them in a formal church service.

John Greenleaf Whittier was a Quaker. If you know anything about 19th-century Quakers, you know they weren't big on "steeple-houses" or organized singing. They sat in silence. They waited for the "Inner Light." So, how did a poem written by a guy who didn't believe in church music become one of the most famous pieces of church music in the English-speaking world? It’s a weird, ironic journey that says a lot about our obsession with finding peace in a loud, chaotic world.

The Drug-Fueled Origins You Weren’t Taught in Sunday School

The verses we sing today are actually a tiny fragment of a much longer, much stranger poem called "The Brewing of Soma." Whittier wrote it in 1872. He wasn't trying to write a prayer for a choir; he was actually writing a scathing critique of religious fanaticism.

In the full poem, Whittier describes a Vedic ritual where people brewed a drink called Soma. It was basically a hallucinogenic cocktail. They’d drink it, get high, and think they were experiencing the divine. Whittier looked at the "revivalist" Christian meetings of his own day—with all the shouting, fainting, and emotional hysteria—and thought, this is just the same thing. He felt people were using "sensual" excitement to fake a spiritual experience.

He was essentially telling his contemporaries to take a deep breath and shut up.

The section that starts with "Dear Lord and Father of mankind, forgive our foolish ways" was his way of pivoting back to what he considered true worship: silence and calm. He wanted people to stop trying to manufacture a religious high and instead focus on the "still, small voice of calm." It’s ironic, isn't it? We now use a lush, emotional musical setting to sing a poem that was originally complaining about... well, emotional settings in religion.

Why the Music Changed Everything

For about fifteen years, these words just sat in a book of poetry. Then along came Garrett Horder. In 1884, he was putting together a hymnal called Congregational Hymns and realized that Whittier’s poem, if you chopped off the parts about ancient drug rituals, made for a beautiful prayer.

But a hymn needs a tune.

👉 See also: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

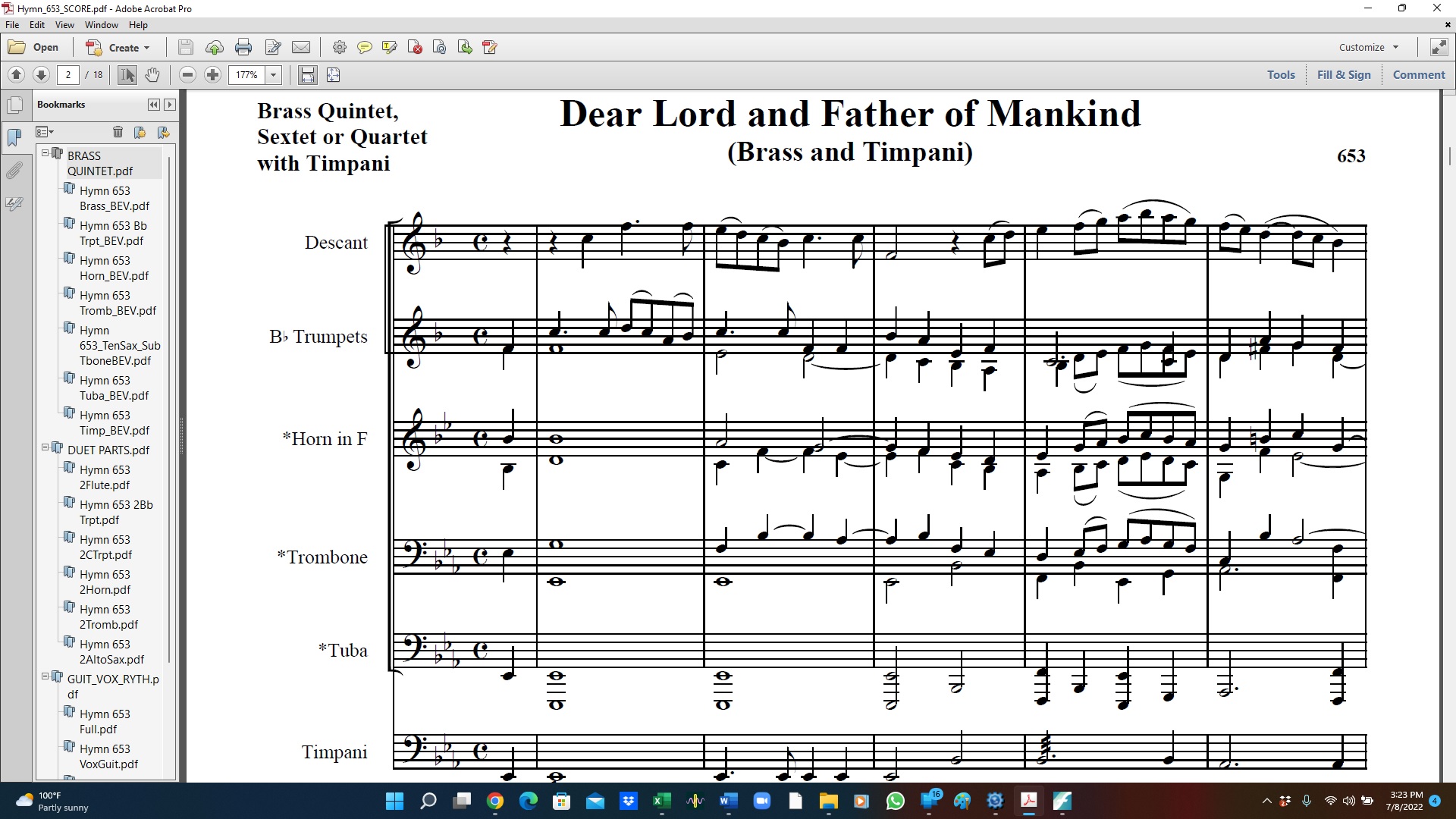

Enter Sir Hubert Parry. He is the heavyweight champion of British "stiff upper lip" music, the same guy who gave us Jerusalem. In 1888, Parry wrote an oratorio called Judith. It wasn't particularly successful. However, there was a specific aria in it called "Rephidim." In 1924, George Gilbert Stocks—the director of music at Repton School—took that melody and paired it with Whittier’s words.

That’s when the Dear Lord and Father of Mankind hymn truly became a phenomenon.

The tune is officially named Repton. It is famously difficult to sing because of that long, rising phrase in the second-to-last line. You know the one. It requires a lot of breath control. But when a full congregation hits that peak together, it creates this incredible sense of swelling peace. It’s become the "unofficial national anthem" of British calm.

The Theology of "Taking it Down a Notch"

Honestly, the reason this hymn stays popular isn't just because the melody is catchy. It’s because the lyrics are basically a 19th-century version of a mindfulness app.

- The Sea of Galilee imagery: Whittier talks about the "peace of Galilee." It’s a reference to the biblical story of Jesus calming the storm.

- The "Sabbath rest": He isn't talking about a day of the week. He’s talking about an internal state of being.

- The "Earthquake, wind, and fire": This nods to the story of Elijah. God wasn't in the big, loud, scary stuff. God was in the silence that followed.

In a world where our phones are constantly buzzing and everyone is shouting for attention on social media, there’s something deeply attractive about singing "drop Thy still dews of quietness, till all our strivings cease." It hits a universal human nerve. You don't even have to be particularly religious to feel the weight of that. It’s about the desire to just... stop. Stop the noise. Stop the performance.

Is it Actually "Boring"?

Some modern critics find the hymn a bit too "Victorian." They argue it’s too passive. It’s all about waiting and bowing and being quiet. If you look at modern worship songs, they are often high-energy, focused on "victory" and "shouting."

But there’s a counter-argument here.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

The Dear Lord and Father of Mankind hymn offers a specific kind of psychological relief that "happy" songs don't. It acknowledges that we are "foolish." It admits we are stressed out. It’s an honest confession of being overwhelmed. Sometimes, you don't want to shout. Sometimes, you just want to acknowledge that you’ve been running in circles and you need to sit down.

The Lyrics You’re Probably Singing (And What They Mean)

Most hymnals use about five or six stanzas. If you look at the original poem, there are seventeen. We skip the parts about "drinking the soul-deceiving juice." Probably for the best.

"Forgive our foolish ways"

This isn't about being a "sinner" in the fire-and-brimstone sense. For Whittier, "foolishness" was the human tendency to look for God in the wrong places—in status, in noise, and in frantic activity.

"In purer lives Thy service find"

This is the core Quaker belief. You don't serve God by singing songs (ironic, again) or performing rituals. You serve God by how you live your daily life. It’s a call to integrity rather than performance.

"The silence of eternity"

This is one of the most beautiful lines in English hymnody. It suggests that there is a deep, underlying quietness to the universe, and we just need to tune our "feverish ways" to it.

A Cultural Powerhouse

It’s been used in movies, it was a favorite of the late Queen Elizabeth II, and it’s frequently voted into the top five of the BBC’s Songs of Praise polls. It has this weird staying power. Why?

Maybe because it’s a protest song.

🔗 Read more: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Think about it. In a culture that demands we be "on" 24/7, singing a song that demands "quietness" is actually a pretty radical act. It’s a refusal to participate in the frantic pace of modern life. It’s a three-minute rebellion against the "stress" of the world.

How to Actually Use This (Actionable Insights)

If you’re a choir director, a musician, or just someone who likes the history of music, there are a few things to keep in mind when approaching this piece.

Don't over-sing it. The biggest mistake people make with the Repton tune is treating it like a Broadway show tune. It needs to breathe. If you’re playing it on a piano or organ, resist the urge to hammer the keys. Let the "stillness" of the lyrics inform the tempo.

Read the full poem. If you’ve never read "The Brewing of Soma," go find it. It will completely change how you view those "peaceful" lyrics. Knowing that the poem is actually a biting satire adds a layer of intellectual grit to the sentimentality.

Use it for transitions. In any kind of event—whether it’s a religious service or a secular memorial—this hymn acts as a perfect "palate cleanser." It transitions the mood from high energy to reflection better than almost any other piece of music in the Western canon.

Watch the phrasing. If you’re singing that fourth verse ("Drop Thy still dews of quietness"), try to hold the phrase until the end of the line. It’s designed to mimic the feeling of falling dew. It shouldn't feel choppy.

The Dear Lord and Father of Mankind hymn is more than just a relic of the Victorian era. It’s a psychological reset. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most spiritual thing you can do is just be quiet. Whittier might have been annoyed that his poem became a song, but he’d likely be happy that people are still searching for that "still, small voice" over 150 years later.

Next time you hear those opening chords, remember the "foolish ways" Whittier was talking about. It wasn't about breaking rules; it was about the foolishness of being too busy to hear the silence. Take a breath. Let the strivings cease. That’s the whole point.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Appreciation:

- Listen to the King’s College Choir version: This is widely considered the gold standard for how Repton should be phrased. Notice the dynamic shifts.

- Compare the lyrics to the book of 1 Kings 19: This is where the "earthquake, wind, and fire" imagery comes from. It provides the biblical context for why silence is so valued in this tradition.

- Research the Quaker "Quietist" movement: This will give you the historical background on why Whittier was so suspicious of loud, emotional worship in the first place.