Numbers lie. Or, at least, they get fuzzy when you're looking back through centuries of rubble and plague. When people talk about the deadliest disasters in history, they usually reach for the obvious ones—the Titanic, Pompeii, maybe the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. But honestly? Those barely scratch the surface. We’re talking about events that didn't just break a city, but fundamentally rewrote the DNA of human civilization.

Death tolls are notoriously tricky. You’ve got official records, which are almost always too low, and then you’ve got "excess mortality" estimates that can swing by millions. It's a mess. But if we’re looking at the raw, staggering impact on human life, the scale is almost impossible to wrap your head around.

The Invisible Killers: Pandemics That Reset the Clock

We like to think of disasters as big, loud explosions. Fire. Floods. Crashing buildings. But the real heavy hitters in the deadliest disasters in history category are usually microscopic.

Take the Black Death. Between 1347 and 1351, the bubonic plague wiped out anywhere from 75 to 200 million people across Eurasia and North Africa. It wasn't just a "bad flu season." It was a total societal collapse. In some parts of Florence or London, half the population just... vanished. You’ve probably heard the nursery rhymes, but the reality was a horrific mix of swollen lymph nodes and absolute terror. It actually changed the economy forever because, suddenly, there weren't enough peasants to work the land. Labor became expensive. The middle class was basically born from a pile of corpses.

🔗 Read more: Robert Peace Explained: The Ivy League Genius Who Couldn’t Leave Newark Behind

Then there's the 1918 Spanish Flu. It’s a bit of a misnomer since it didn't start in Spain (they were just the only ones not censoring their newspapers during WWI), but it killed more people than the Great War itself. Estimates put the toll between 17 million and 50 million, though some researchers like Frank Macfarlane Burnet suggested it could have been closer to 100 million. It targeted the young and healthy. Their own immune systems overreacted and filled their lungs with fluid. It was fast. Brutal.

When the Earth Itself Breaks

Geological disasters are different. They’re sudden. One minute you're eating dinner, the next, the ground is a liquid.

The 1556 Shaanxi Earthquake in China is widely cited by historians as the most fatal seismic event ever recorded. It happened in the Ming Dynasty. Roughly 830,000 people died. Why was it so bad? Mostly because of the yaodongs—artificial caves carved into loess cliffs where millions lived. When the earth shook, the cliffs simply disintegrated. They were buried alive in their own homes.

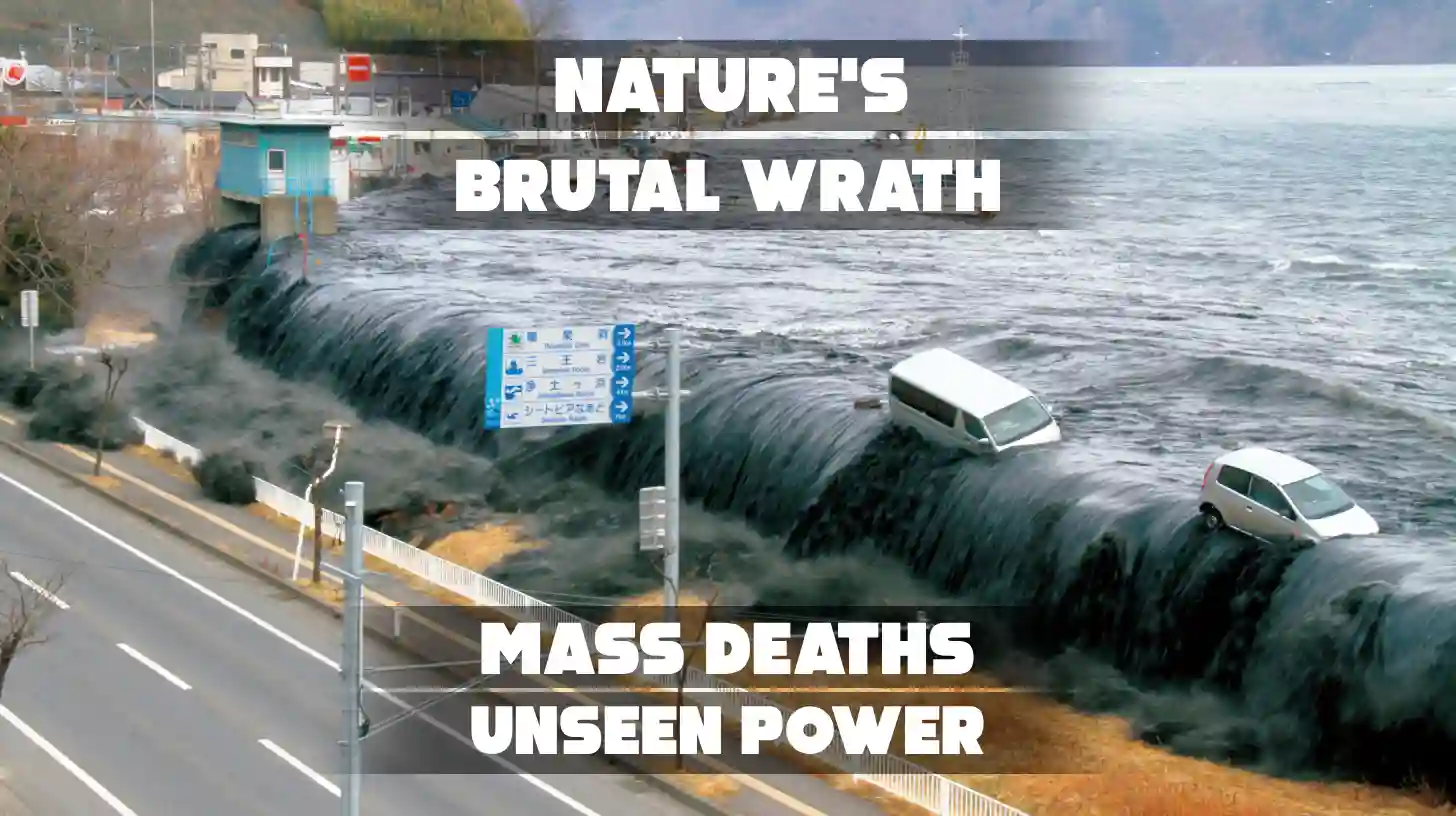

We also have to talk about the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. This one feels more "real" to many of us because it was caught on camera. It was a 9.1 magnitude quake that triggered a wall of water traveling at the speed of a jet plane. It hit 14 countries. About 227,898 people died. It’s a specific number, but even then, thousands remained "missing" for years. It fundamentally changed how we monitor the oceans. Before 2004, the warning systems in the Indian Ocean were basically non-existent. Now, we have deep-ocean sensors, but even technology has its limits when nature decides to move a tectonic plate by 50 feet.

The Floods No One Remembers

If you ask a random person about the deadliest disasters in history, they rarely mention water unless it's a shipwreck. That’s a mistake. The 1931 Central China floods were likely the single most lethal natural event in human memory.

After a decade of drought, the Yangtze, Huai, and Yellow rivers all flooded simultaneously. It wasn't just a big splash. It was months of inundation. The death toll? Estimates range from 400,000 to—get this—nearly 4 million people. Most didn't drown. They died of cholera. They died of typhus. They died because the crops were gone and there was nothing left to eat but bark and soil.

The Yellow River is often called "China’s Sorrow" for a reason. In 1887, it flooded and killed somewhere between 900,000 and 2 million people. When the dikes break on a river that sits higher than the surrounding plain, there is nowhere to run. It's just a flat expanse of rising mud.

Why the Data is Often Wrong

You have to take historical numbers with a grain of salt. For instance, the Great Tangshan Earthquake of 1976. The official death toll from the Chinese government was 242,000. But outside observers and later reports suggested it was actually closer to 655,000.

Why the gap?

- Political Optics: Governments hate looking unprepared.

- Logistics: In the chaos of a disaster, who is actually counting?

- Definition: Do you count the person who died of an infection three weeks later? Most historical records didn't.

We also tend to ignore "slow-motion" disasters. Famines are often categorized as political or economic, but they are disasters nonetheless. The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 killed 10 million people—about a third of the population. Was it a natural disaster because of the monsoon failure? Or a man-made one because of the East India Company's policies? It’s usually both. That intersection of nature and human error is where the highest body counts are found.

The Volcanic Wildcard

Volcanoes don't kill as many people as floods, but when they go off, they change the entire planet. Mount Tambora in 1815 is the gold standard for this. It didn't just kill the 10,000 people on the island of Sumbawa instantly. It blasted so much ash into the stratosphere that it blocked the sun.

👉 See also: The Nashville School Shooter Manifesto: What the Leaked Documents Actually Reveal

1816 became the "Year Without a Summer."

Frost in July in New England.

Massive crop failures in Europe.

Riots in the streets of France.

The total death toll from the resulting famine and disease is estimated around 71,000 to 100,000, but the ripple effects lasted years. It's a reminder that a disaster in one corner of the globe can starve someone thousands of miles away.

Surviving the Next One: Actionable Reality

Looking at the deadliest disasters in history isn't just about morbid curiosity. It’s about patterns. We can’t stop a tectonic plate from slipping, but we can stop the buildings from falling on us.

If you live in a high-risk zone, the data shows that the "immediate" survivors are almost always those who have a localized plan that doesn't rely on the government. After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, the communities that fared best were those where the "Tsunami Tendako" tradition—a local rule where everyone runs to high ground individually without waiting for others—was practiced.

Steps to take now:

- Stop relying on your phone. In a major disaster, towers go down or get jammed. Have a paper map of your city and a designated meet-up spot that isn't your house.

- Water is the primary killer. Most deaths in the 1931 floods and the 2004 tsunami came from waterborne illness or lack of clean supply. A simple $20 life-straw or a stash of purification tablets is statistically more likely to save your life than a fancy survival knife.

- Audit your structure. If you're in an earthquake zone, check if your house is bolted to its foundation. The Shaanxi disaster proved that it’s not the shaking that kills; it's the roof.

- Understand the "Double Disaster" effect. The first hit (the quake/the storm) is rarely the deadliest part. It’s the second hit—the lack of sanitation, the fire, or the cold—that racks up the numbers. Prepare for the month after, not just the hour of.

History shows us that humans are incredibly resilient, but we’re also forgetful. We build cities on floodplains and vacation homes on fault lines. The scale of these past tragedies serves as a blunt reminder that the planet doesn't really care about our zoning laws.

Refining our infrastructure and maintaining a healthy level of skepticism toward "official" safety ratings is the only way to ensure the next event doesn't end up on this list. Focus on the basics: clean water, structural integrity, and local communication. Everything else is just noise.